The “loose, baggy monster” (Charles Dickens)

Charles Dickens (7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870)

It is important to remember that many of Dickens’ books were serialised, hence their great bulk crept-up on the audience, so intent on the trees that they forgave the tangled, unstructured wood. Peter Ackroyd, in his massive (and borderline prurient) biography, noted that, in America for example, his readers “greeted the arrival of the latest sheets of The Old Curiosity Shop with cries of “Is Little Nell dead?”” It is all very well to be snobbish about Dickens – F.R. Leavis calling him a genius but only a genius as an ‘entertainer’ for example – but we think Walter Allen gets near to the mark when he says, in The English Novel (1954): “Dickens was the great novelist who was also the great entertainer, the greatest entertainer, probably, in the history of fiction. Much of the misapprehension of him comes from this fact, and from the related fact that, formally, he was a man of little education writing for a public often more poorly educated than himself.”

What stand out in Dickens are the enormous range of vivid characters, striding the spectrum of his made-up worlds, from the heroic to the grotesque, and moreover, his depth for feeling. In comedy, particularly, he invested enormous emotional energy, never forgetting the rule that ‘all comedy is in some way black.’ Increasingly, his novels drew an angry bead on an imperfect world, and his array of comedic weapons (such as satire), were wielded in a frontal assault on it, so much so that his ‘entertainments’ became actual planks of reform. His epitaph stated:”He was a sympathiser with the poor, the suffering and the oppressed; and by his death, one of England’s greatest writers is lost to the world.” Not that he was political in the sense we have of that word now, rather that he felt for the disenfranchised in a deep and genuine way, rebelled against a reactionary stance regarding them, and spoke for them in the best way he knew. (Not for nothing had he despaired of his time in the blacking factory.) For that reason, George Santayana wrote of him: “I think Dickens is one of the best friends mankind has ever had.”

Best to know the man through his books and even though Dickens is no longer compulsory in schools (more’s the pity), simple recitation of titles, or even characters, resonate today: Oliver Twist (1837-39); David Copperfield (1849-50), Great Expectations (1860-61); A Tale of Two Cities (1859); A Christmas Carol (1843); Hard Times (1854); and one of the greatest novels in English, Bleak House (1852-53). Also, think Ebenezer Scrooge, Fagin, Mrs Jellyby, Uriah Heep, Mr Creakle, Miss Havisham, Micawber, Oliver Twist, Sydney Carton, Mrs Leo Hunter and her poem, ‘Expiring Frog,’ Pip, Magwitch, Mrs Gamp, Bill Sikes, Krook, Gradgrind, Madame Defarge, Tulkinghorn, and so on…A close relative recently pointed out that our current, troubled times (and the bizarre types inhabiting them), could use a new Dickens, or a few of him.

George Orwell wrote (1939) a seriously good essay about Dickens, in which he memorably concluded:

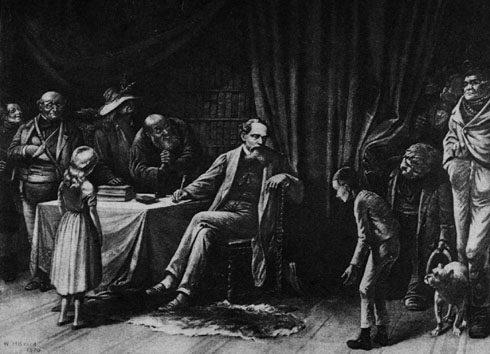

“When one reads any strongly individual piece of writing, one has the impression of seeing a face somewhere behind the page. It is not necessarily the actual face of the writer. I feel this very strongly with Swift, with Defoe, with Fielding, Stendhal, Thackeray, Flaubert, though in several cases I do not know what these people looked like and do not want to know. What one sees is the face that the writer ought to have. Well, in the case of Dickens I see a face that is not quite the face of Dickens’s photographs, though it resembles it. It is the face of a man of about forty, with a small beard and a high colour. He is laughing, with a touch of anger in his laughter, but no triumph, no malignity. It is the face of a man who is always fighting against something, but who fights in the open and is not frightened, the face of a man who is generously angry – in other words, of a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.”

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

1 Comment