The Travelling Egyptologists

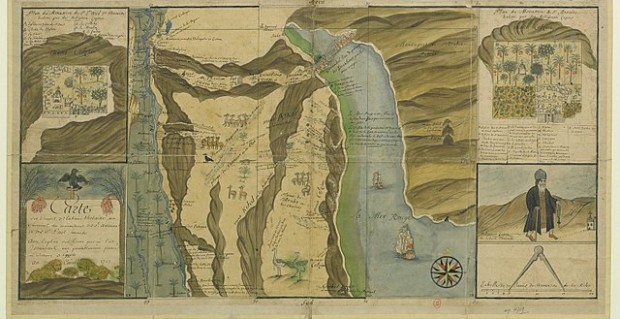

1717 map of White Nile and environs by Claude Sicard

Lecture at Adelaide, 21 September 2017

Think Egyptology and the enthusiastic amateur thinks Champollion, Sir Henry Rawlinson, David Roberts, James Breasted, Flinders Petrie, or Howard Carter; possibly Boris Karloff, Kingsley Amis and Robert Conquest. But The Varnished Culture was ignorant of the seminal work of Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-1884). Drawing on the work of Champollion, Lepsius virtually established the discipline of Egyptology, paving the way for the more vaunted discoveries of the early 20th century.

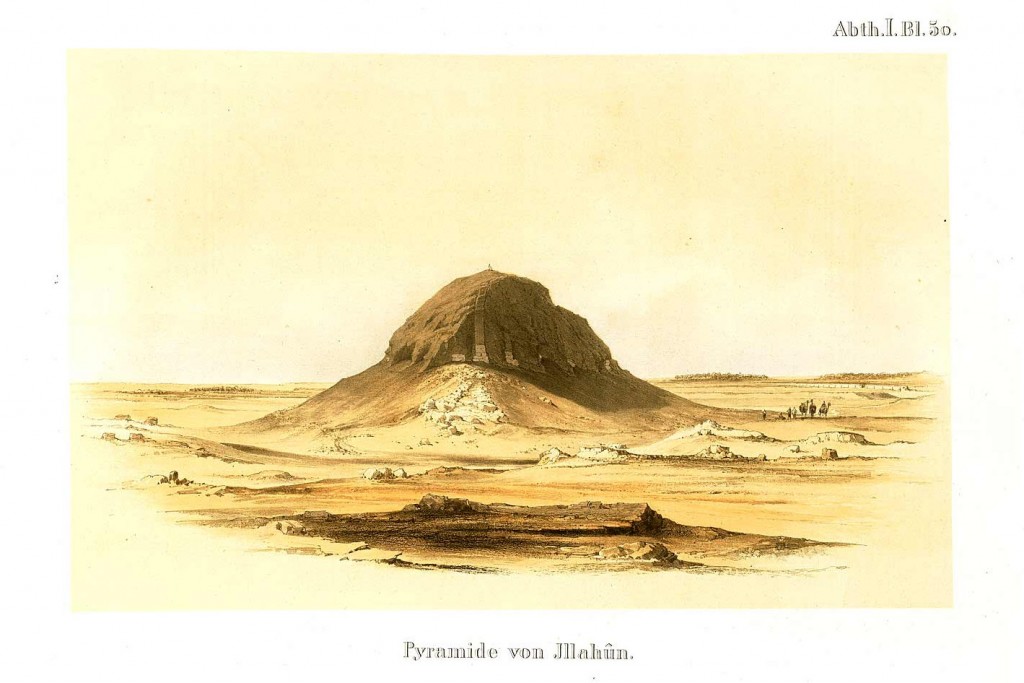

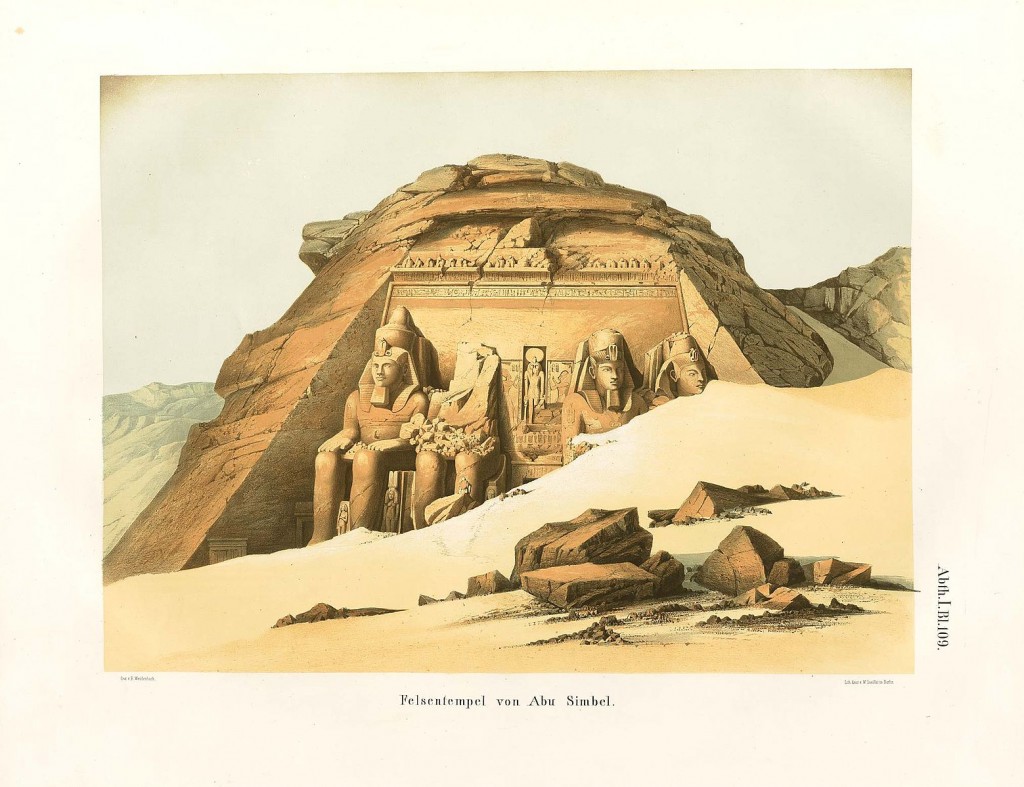

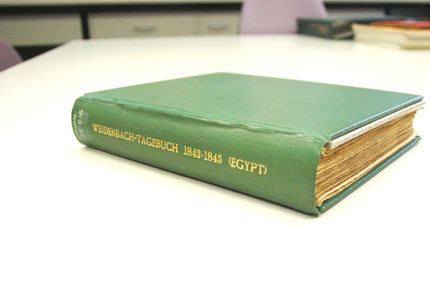

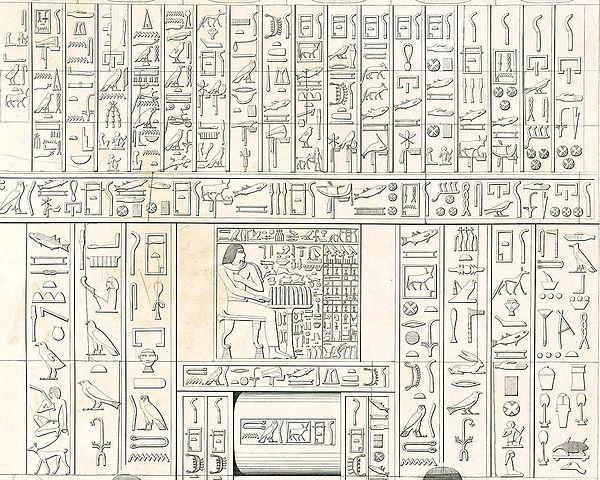

The Lepsius expeditions to Egypt and Nubia (Sudan) 1842 – 1845 (sponsored by the King of Prussia, to catalogue, and in some instances loot, the ancient monuments), led to the publication of a twelve volume compendium Denkmäler aus Aegypten und Aethiopen (Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia).

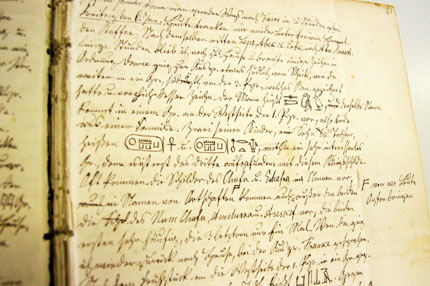

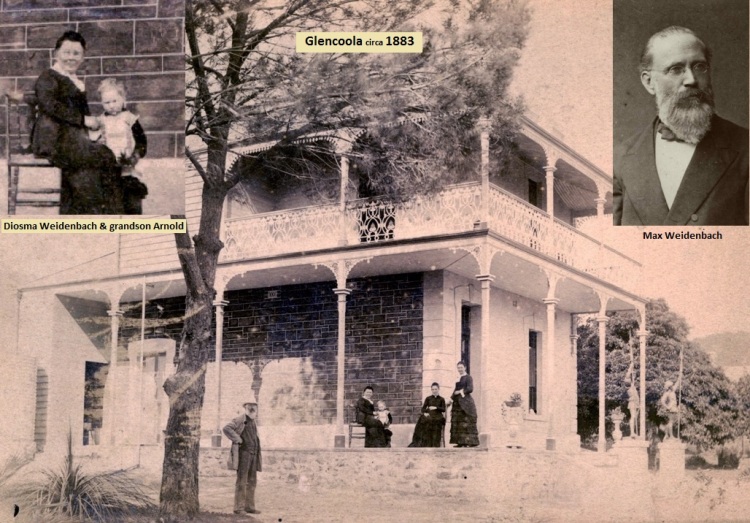

Along for the ride was a young man called Max Weidenbach (born 1823), an expert in drawing hieroglyphs. But those efforts aside, he also kept a meticulous diary, which documented a range of matters not considered important by the more serious and venerable members of the dig, such as the local arab team members, logistical difficulties on the various digs, social gatherings, and so on.

We move now to Adelaide, where Michael O’Donoghue, a research fellow at the South Australian Museum, found several shabtis (ancient Egyptian funerary statuettes) and sundry other pieces, donated to the Museum in the 1940s by a “Mrs Arnold.” Who the heck was she, and how did she come by this ancient treasure?

O’Donoghue dug deeper. It turned out that Mrs Arnold was the widow of an Edwin Arnold. Edwin had originally been Arnold – Arnold Edwin Weidenbach – nephew and principle beneficiary of the estate of the late Max Weidenbach, who had passed in 1890. Arnold had anglicised (and reversed) his name during WWI, a common practice then.

It was during preparations for a Weidenbach family reunion that Mr O’Donoghue received a request for a viewing of the donated items of Egyptology. It was known that Weidenbach had kept a diary of the Lepsius expeditions but it could not be located. Why would Mrs Arnold not donate that document along with the other priceless pieces?

By miraculous serendipity, it was discovered that she did. Because the diary was bound, it went to the museum’s rare books library rather than archives, which had been thoroughly, fruitlessly searched. The green volume blocked in gold and containing hundreds of pages of detailed (and fortunately, neat) handwritten entries of Weidenbach, was finally unearthed (see images above, c/- SA Museum). (This oversight seems a bit of a rookie mistake, but that is the genius of hindsight).

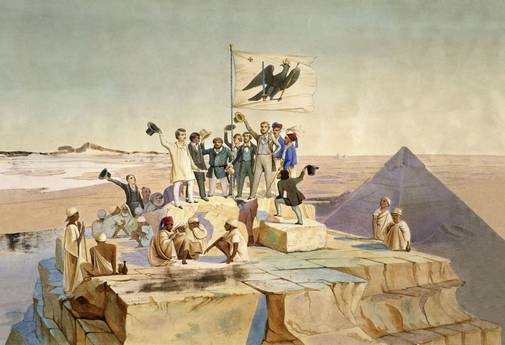

Expeditionary party atop Cheops’ monument, to salute the birthday of patron King Friedrich Wilhelm IV, by Johann Jacob Frey, 1842

Dr Susanne Binder, Languages and Cultures and Department of Ancient History of Macquarie University, is translating the diary, painstaking work that will inform and illuminate the Lepsius archives. Dr Graller of the Lepsius Archive in Berlin expounded upon the vast store of material already held.

Weidenbach’s forte was the reproduction of hieroglyphics.

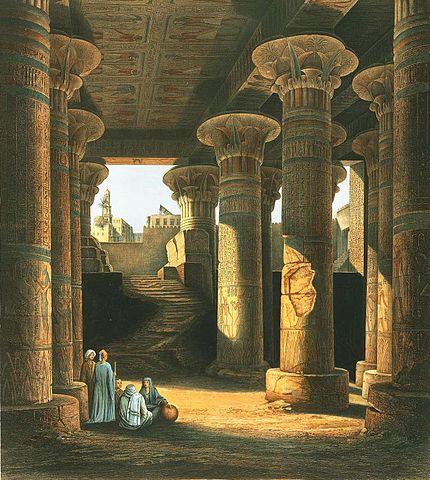

The expedition covered a lot of ground – first at Giza and then south as far as Khartoum, and along large stretches of the Blue Nile in Sudan.

Photography was an infant, so accurate drawing was vital. The expedition, returning north to Thebes and up the White Nile, including the famous Valley of the Kings, employed these drawings to faithfully record monuments, now rendered as dust by time and strife.

Photography was an infant, so accurate drawing was vital. The expedition, returning north to Thebes and up the White Nile, including the famous Valley of the Kings, employed these drawings to faithfully record monuments, now rendered as dust by time and strife.

Max came to Adelaide in 1849. He made a lot of money in the Victorian gold rush, invested in land at Glen Osmond (and bought a few BHP shares), settling down to a life of leisure in the Adelaide foothills (his house still stands in the City of Burnside, as Abergeldie Private Hospital). His sister-in-law, Diosma, and her grandson Arnold, came to live with Max after Diosma’s husband (Max’s brother) died. Max used to tutor Arnold every morning (he was reputedly a quite strict polymath), and he passed way peacefully at age 67, leaving a large estate.

Michael O’Donoghue, who rounded-out this entertaining evening with an account of Weidenbach’s life in Australia, mentioned that Max made two trips back to Germany. It would be interesting to find a diary of those events (were the Lepsius expeditionary party re-united?) and Max’s personal sketchbook of the expedition (featuring his interests in native flora and fauna rather than ancient artefacts), in order to fully round-out the Lepsius archive.

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

0 Comments