The Varnished Culture's Thumbnail Reviews

Regularly added bite-sized reviews about Literature, Art, Music & Film.

Voltaire said the secret of being boring is to say everything.

We do not wish to say everything or see everything; life, though long is too short for that.

We hope you take these little syntheses in the spirit of shared enthusiasm.

She Said

(2022)

Yes, it’s all ‘She Said’ in this tedious, overblown 90 minute polemic from director Maria Schrader. Anything ‘he says’ is misogynistic and stupid, ipso facto, because the speaker is a man. The scene is set early on with gratuitous Trump-bashing. Then whispers about Harvey Weinstein’s predatory behaviour are heard and leapt upon voraciously by our female reporters (they are, apparently, the only ones doing a real job apart from, possibly, Anderson Cooper who is also on to it, (no surprises there)). Everyone’s aghast. The ‘casting couch’ is such an evil and new concept (but only to be expected).

Weinstein is a grub and not the only one in Hollywood, true. But the utter glee and self-aggrandisement with which Meghan Twomey (Carey Mulligan) and Jodi Kantor (Zoe Kazan) (the real life New York Times journalists behind the original exposé) pontificate and air-punch when they get hold of a minor celebrity who will talk (sorry Ashley, sorry Rose) is simply wearisome. There’s some mysterious thing going on with Saint Gwyneth Paltrow whom the writers want to name as a complainant but just can’t quite.

The music, the physical trembling with emotion, the portentous voices and the meaningful looks are risible. We see our heroines juggling massive workloads and new babies. Post natal depression gets a moment, as do nasty men in bars. Male lawyers are dumb and must be countered with smug eye-rolling. A male editor is ok, as long as he is black and restricts his input to, “You go get ’em!” and “we’ve got a deadline!” Patricia Clarkson looking fabulous (is that ok?) trails about, supporting our reporters in a soft voice. If she’s embarrassed, Carey Mulligan should be hiding under the bed in shame. Miss this dross and watch her in Never Let Me Go and a truly powerful feminist story which leaves this weak entry for dead, “Promising Young Woman“.

She Said tries to be All The President’s Men but it is so, so not. She said. Me Too.

Continue Reading →Good

(written by C. P. Taylor (1981); Directed by Dominic Cooke, Harold Pinter Theatre, London, 25 June 2023)

Regarding the grand achievements of the Third Reich, “As with Stalin’s Great Terror, only a madman could guess what was on the way. Even the perpetrators had to go one step at a time, completing each step before they realised that the next one was possible.”* In “Good,” A liberal German Professor of literature (NOT Victor Klemperer), named John Halder, becomes involved with the Third Reich’s war machine and the Final Solution. Halder, a ‘good man,’ shows all the moral courage of Albert Speer and all the sense of duty and honour of Reinhard Heydrich. Mere cool intellect does not confer simple warm human decency or tough adherence to tradition and principle, something the old religions used to try to drum into us.

In this production, each incremental step to the Holocaust is shown: Hitler’s election; the Berlin University book burning; exploitation of the assassination of Ernst vom Rath and subsequent Kristallnacht; War and Shoah. Throughout, Halder’s development (or descent) is accomplished because, pace Hannah Arendt, the emptier the vessel, the easier to fill with poison. The play takes no baby-steps: we hurtle towards the denouement at a frenetic pace, as Halder engages with multiple characters – his best (only) friend (a Jew), his demented mother, his wife, his lover, various Nazi apparatchiks. These exchanges chop and change every few seconds, or so it seems, but we did not find this overly confusing, albeit the whole piece is overly talky. Halder was played by David Tennant in an excess of intensity: whilst impressive, a bland and unemotional reading would have been more apt. The sundry supporting roles were played by Elliot Levey and Sharon Small, very well indeed, although an ominous and silent figure joins the stage at the finale. The set is claustrophobic and stark, a cornered wall with apertures for ovens to accommodate books and other things for burning.

The dramatic theme is sledgehammered in up front by Halder, at dinner in Frankfurt, telling friend Maurice how Goethe ignored a begging letter from Beethoven. This becomes the trope for Halder’s moral decline, particularly his failure to secure Maurice’s exit visa from an increasingly anti-Semitic nation. It is a poor start in a play about morality: how about explaining that Goethe was ill to almost the level of mortal danger when the letter arrived? But let that pass. At first, Halder meets his friend’s fear of the Nazis with skepticism (“just a balloon they throw up in the air to distract the masses.”) Then Halder joins the Party (it’s just easier). The characters emblematize the febrile atmosphere of Nazi Germany, to a point where they seem one-dimensional when in such a world of State-sponsored insanity they actually are forced to be. Music, that great mnemonic, accompanies the inside of Halder’s head as he heads down the well-intentioned stairs to Hell, leaving dying Weimar (jazz), passing by unfashionable Catholicism (Schubert, Chopin) and arriving with a thud at Wagner (an obvious but silly conceit).

For advancement, vanity, and an easy life, Literature Professor Halder starts by shoveling books into the furnace, and finally channels his inner Mengele and Eichmann at Auschwitz, where an old friend turns up. Clive James, reviewing the TV drama “Holocaust” in ‘The Observer’, 10/9/1978, whose comment is quoted above, said further: “There is no hope that the boundless horror of Nazi Germany can be transmitted entire to the generation that will succeed us. There is a limit to what we can absorb of other people’s experience. There is also a limit to how guilty we should feel about being unable to remember.” This sums up the difficulty of dramatic renderings of insane epochs such as the Third Reich or the Great Terror (or for that matter, the Spanish Inquisition, the Reformation, the Apartheid, the Katyn massacre, Srebrenica, The Troubles, etc…) – they stretch the limits of our credulity; they stretch the limits of our ability to process the truth. For these and other reasons discussed above, Good is not Great (and in fairness, could probably never hope to be).

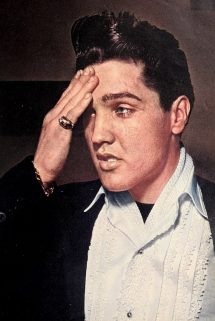

Continue Reading →Edge of Reality

(Created by Paul Grabowsky, Adelaide Festival Centre, 14 June 2023)

Elvis Presley and Cabaret? But of course! If you Can Dream, avoid that Kentucky Rain, have a Little Less Conversation, perhaps have you Always on Our Mind, and do it My Way, it could work. And this night, it kinda-did, care of Paul Grabowsky’s absolutely clever re-working of the arrangements of the King’s greatest hits (and some lesser mortals), with a terrific jazz/rock/fusion band (piano, guitar, cello, clarinet, trumpet, fiddle, drums, glockenspiel?) and starring celebrated Australian vocalists Joe Camilleri and Deborah Conway, Edge of Reality is a unique tribute to Elvis Presley that the King would have liked, although some of his fans would not..

Elvis would have asked for the songs to be sped-up, but we liked most of the arrangements (see below), which Conway and Camilleri sang lustily and with affection (though not always to the requisite note or lyric). At one stage, early in the evening, Conway tried a dramatic riff of the King, in his Vegas cups, complaining about the press reporting him as “strung out.” As that soliloquy was neither developed, nor reflective of the sad truth, it stuck TVC as passing strange. But let that pass.

Conway sang great versions of “Burning Love” and “Hound Dog” and then Joe gave us a smoking version of “Mystery Train,” (one for aficionados) and then “True Love Travels on a Gravel Road” (one for gnostics). At this stage, one wag in the crowd shouted “Where’s Elvis?“, to which we wanted to reply in the words of Tommy Lee Jones in Men In Black: “Elvis isn’t dead. He just went home.” But before he went home:

There was Deb Conway with a jaunty version of “Don’t Be Cruel,” and a great cocktail-lounge version of “Love Me Tender.” Then a real highlight: a saxophone duo leading into an almost unbearably slow, dark, weird and wonderful version of “Edge of Reality” by Camilleri, worthy of Peter Gabriel in his most imperious mood, and then Conway gave us a jazzy Copacabana version of “That’s All Right.” Joe weighed in with a truncated “In the Ghetto,” a funky “One Night With You” and then Deb attempted “Unchained Melody” which would strain anybody. Joe then did a slow-hand version of the classic “Always on my Mind,” and Deb did the classic “Suspicious Minds” to a great rocking beat, but surprisingly sexless (is is misogynistic to complain that a lass can’t sing the songs of the quintessential lad? Discuss). And the mangled line “Let’s not let a good thing die” was itself mangled.

But the encore was a great hard rocker, “Viva Las Vegas” and then Elvis left the building. A very worthy effort!

Continue Reading →Eurovision 2023

Ah Eurovision! How we love you – always oozing zeitgeist. As the fashion of 2023 is virtue-signalling, so Eurovision 2023 is all woke and everything. But not even the po-faced killjoys of intersectionality politics can strip the time-honoured Eurovision Song Contest of its retro, delusional charm and Martian qualities. No! Though it nods to the real world, Eurovision will never be mainstream or proper. It is…Eurovision…

So the 2023 Grand Final (in Liverpool, England because the 2022 winner Ukraine is at war) started true to form with an inexplicable number featuring Cousin-It ‘dancers’ in ghillie-suit-womble ensembles, a bit like those giant vertical mops that escape from the carwash in that tv ad. For some reason they were joined by a man in a very stupid pink fur Gilligan hat. They, and several other apparently hilarious types hopped about to third-rate hip hop music for 2 or 3 hours. Awful. Excellent! Nil points! Following that nonsense there was a flag parade studded with random and spontaneous songs by various previous contestants including the large, threatening, gyrating Ukrainian person with a star headdress that everyone remembers (Verka Serducha, Ukraine) from 2007 (the fear, if not the details) and babooshkas on guitar.

When the hosts, a medium size woman no one knew, a tiny Ukrainian chick, an immense English woman called Hannah and a lackluster Graham Norton informed us, to our horror, that there were no less than 26 acts to follow, we heard the gasps around the world as viewers wondered just how many tequila shots a human can take. Oddly, the nameless woman and the little Ukrainian disappeared early on, returning now and then, apparently to assist poor Graham who was clearly uncomfortable and stunned, staring abjectly at the camera while Hannah towered over him, mugging and cackling like Kamala.

We shall mention at this point (because it doesn’t fit anywhere) that the Australian ‘hosts’ Myf Warhurst and Joel Creasy (with groovy pink hair) were also out of their depth and, despite their determined cheerfulness, rather unnecessary. The ‘interview’ toward the end of the show, when the anonymous woman said how grateful they all were to Myf and Joel for being there and Myf and Joel replied that they were so grateful to be there, was even more cringeworthy than Joel’s drooling all over Marco from Italy.

Now, a reminder of our voting systems. We award points out of 5 for how an entrant’s song might manage when let loose into the real world bare-naked; and we award Euro-points out of 5 for the ineffable “Eurovisionness” of each act. In particular, points are traditionally awarded for: 1. Dry ice 2. Contortionists 3. Bad Dancing 4. Any item of Clothing being Torn Away 5. Dwarves 6. Angel Wings or Mock Flying 7. Clowns 8. Piano as Furniture 9. Bearded Ladies 10. Puffs of Smoke. This year though, having watched the whole ghastly thing, we see that we need to start oozing the zeitgeist too. Dry ice and puffs of smoke are now compulsory for every Eurovision song and not even worth mentioning. Let’s see, as we trawl through all 26 of these magnificent offerings, what might replace them.*

Let us dive into the treacle and garum that is Euovision 2023!

AUSTRIA. Teya and Salena lead us all in snoring through “Who the Hell is Edgar? [Allen Poe]”, prancing about in front of a huge typewriter in awful bomber jackets , stringy corsets and loose pants. Not the worst song of the evening (frightening, we know) and the only vaguely literary (or even literate) entry. 1 point for the song and 2 Euro-points for ugly outfits and guitar girl dancers.

PORTUGAL. Mimi Cat, a blonde woman in an awful floofy red dress and long pink gloves grinned her way through some sort of anti-sultry cabaret mess-up. It’s best lines, ‘”I’m crazy. Completely senile”. 0 for the song, 3 for how awful it all was.

SWITZERLAND. “Water Guns” by a pretty boy, Remo Forret in sheer black. A dreary ballad slightly enlivened by sprinting and interpretive dance with stretchy strings and strobe lighting. “I don’t wanna be a soldier, soldier”. A generous 1 for the song and 3 Euro-points for obvious reasons.

POLAND. By Sir Terry Wogan’s beard! this was terrible. Does Blanka think she is hot or what? No wonder she warbles thinly about being “Solo”. The retro video effects were not the last of the night. Unfortunately, neither were the winking or the hair being blown all over the face by a big fan. 0 for the song but 3 for how Eurovision can turn a girl’s head.

SERBIA. At this point we streamlined the first part of our scoring system, only noting the score for a song on the rare occasion it rated more than 0. Things were looking that bad for the actual ‘music’. The vague resemblance of this stinker to “Fade to Grey” was as good as it got. Another pretty boy, this time lying in a ‘”technological flower'”(his words) in a New Romantics outfit while whining quietly, “consensus is burning” opened the number. Robot dancers jerked and a final screen read “ENERGY DEFEATED”. Horrendous. Worthy of 5 Euro-points right there.

FRANCE . La belle Francois can always be relied upon for providing the snore of the evening – sung in French of course. A Lady Gaga type. ‘La Zarra’ in a sparkly dress “inspired by the Eiffel Tower” (overpriced, outdated and useless) topped a great platform thing with a flat biscuit perched jauntily on her curls. She appeared to be tied to a pole, which would explain the whining. Too dull for even more than 2 Euro-points.

CYPRUS. Now this is cheating. Some tanned Australian guy called Andrew Lambrou, whose grandparents were from Cyprus does publicity on a beach, puts on earrings and wanders onto a stage in Liverpool warbling “Break a Broken Heart” (which as an English speaker he must know makes no sense). Not a bad voice, but a wretched song, Andrew. You get 2 Euro-points only for water effects and bare feet, surfer boy.

SPAIN. Blanca Paloma (where have we heard that name before?) got talked into wearing a burgundy lolly wrapper as a one-shoulder corset accessorised with liquorice straps around the arm. And baggy white pants. That, and the women reaching out to touch her through string curtains hurt our eyes in the proper Eurovision way. The red and black theme, ullulation, clapping and silhouettes were perfectly in keeping with every other dull act in Eurovision night 2023. As Paloma sang, “may your eyes like the sun illuminate me at night”. Cosmology is different in Spain. It was a complete mess apart from Blanca’s white platform shoes (platforms were a feature of the show). The song was called “Eaea” which describes our feelings too. 3 Euros.

SWEDEN. OK, this poor skinny woman (Loreen, a previous winner) was attempting a Cosplay show between two light boxes and got stuck. We gave her 1 point for her energetic song, “Tattoo” which reminded us at times of that other Swedish number, “The Winner Takes it All”. (Near the 50th anniversary of ABBA’s famous Eurovision win. Funny that). Her hideous rat-coloured stringy snake costume was designed by Bjork while watching aerobics on Channel Druid. Loreen looks a bit like Patti Smith and she gives good hair so all that adds up to 4 Euro-points.

ALBANIA. Albina and Kemedi Family represented Albania this year. Well, at least the family were proud of Albina and waved their hankies to show it. What is Albanian for ‘Kudos’. ‘Theresas’? Well, Theresas to Mum or the aunty who ran up Albina’s space suit from a desert planet and wrote the immortal lines, “They’re falling apart. Forgetting they have a home. Kids at the table”. Bless. So dull that they wasted all that potential for just 2 Eurovision points.

ITALY. Surprise! A chap called Marco in leather pants and a spangled vest smouldering away Italian Variety Style. ‘Due Vite’ was the song. We were distracted from Marco’s not too bad voice by the backing dancers bouncing up and down on trampolines in silhouette. Marco sang “And still I don’t know your desert that well”, “And we screwed away another night outside a club” before falling to his knees. 3 for that, Marco. Very good.

ESTONIA. We at TVC want Estonia to win so that we can see Eurovision in its flesh in Tallinn. Alas, that wont be happening anytime soon. Our hearts sank as Alika tripped onto the stage in some weird convoluted periwinkle number with strings, a cut-away leotard, an oversized jacket, draggy skirt pants with a side train and I don’t know what else. She did have a self-playing piano and she did some finger gymnastics which is always good. Her voice was better than the peculiar get-up suggested, so she gets 1 for the song and 2 Euro-points.

FINLAND. Finland, Finland, Finland where I do not want to be if this lot are indicative of its artist class. Kaarija, an odd looking man with odd hair regaled us from a wooden crate with “Cha Cha Cha”. He croaked his way through the metal bit to the dance mix. The segue didn’t hurt because we were distracted by his neon green puffer sleeves and black spiky plastic pants. There was more bondage with big rubber strings (pink this time), gorilla walking and a human centipede. Kaarija tried his hardest for Euro-points – silhouettes, a large shadow, strobes and a lizard tongue effect. “I’m staying on this bar stool until I slide off’ he said, along with thousands of tequila sozzled viewers from Brussels to Bondi. 1 for the not totally tuneless song and 5 Euro-points for the totally revolting style. Eurovision as its best – we thought…but wait, Germany is yet to perform its usual drivel and this year there’s Croatia….little did we know…

CZECHIA. What a shame Turkiye and Eswatini aren’t voting tonight. Vesna, 6 fresh-faced women in pink culottes with one long plait each (which is all they can afford in Czechia) meandered about out of synch, declaiming “My sister’s crown don’t take me down” and “We’re not your dolls”, the latter accompanied with marionette actions. They finished with fists raised for the sisterhood. 1 for the song. 3 Euro-points but sister, it was dull.

AUSTRALLIA. A competent band from Western Australia, Voyager, were too stylishly kitted out in glitter-check. The song began with the lead singer in a car**, a keyboard for passenger. A nicely incomprehensible start with a touch of the European incel about it, but it wasn’t enough. Nor was the long hair and fan action. Just not enough Eurovisionness for Euro-points. 2 points for “Promise”, their anthemic number. Is this ultimate failure – points for a song but no Euro-points?

BELGIUM. Gustaph, an ageing Boy George in pink, white platforms and a big dumb white hat of the type Pharrell Williams like to torture us with, sang “Because of You” quite nicely, all things considered. He was careful to make a great show of diversity, including drag video and a contortionist in white and pink with a tail and pom-pom. Surprisingly we will give Gustaph 2 for his song but, not surprisingly, only 2 for Euro magic because it was a bit try hard (see Germany – every year).

ARMENIA. Like many of the lasses in 2021, Brunette has been practising being Ariane Grande in her bedroom. She warbled away about her ‘Future Lover’, or herself or someone, being “abandoned far away, far away you are” before changing to an elfin hip-hop karate dance number without any singing (if you could call it that anyway). Still, she had long laced boots and thought she was the sexiest thing since Blanka; that’s worth 1 Euro-point.

MOLDOVA. Pasha Parfeni is a sort of earth father hippie crouching Japanese Buddhist Moldovan guy and that’s what you get on stage. His singers wore tall Indonesian style hats. There seemed to be a mystic marriage. Pasha’s flautist was a dwarf in a mask with ear feathers, so 4 Euro-points for that. Curiously we didn’t hate the song and gave it 2. Perhaps for authentic insanity and self-absorption.

UKRAINE. The two guys of Tvorchi were next with Heart of Steel. Actually not a bad song, and we give it 3 points, despite all the sentimental nonsense, the yellow and blue, the glitter gloves, the Earth balloons, the wave effects and over the top retro screen effects. We felt a Daft Punk- Kraftwerk-in-a-cathedral-from-Tron vibe.

NORWAY. Alessandra wore a hideous Anne Boleyn in space outfit whipped-up by Albina’s mum with a steamer for a hat and a cape. She hired bad barbarian folk dancers, gave them light sticks and told them to screech a lot. Despite all her sins we give her 2 points for ‘Queen of Kings’ and 1 Eurovision point.

GERMANY. Germany Germany Germany. Germany has a lot to answer for, and their androgynous (they wish) metal band Blood and Glitter (stupid name of the night) is not the least of it. I can’t read my own writing – was their song called “Lord of the Zop”? Probably not, but it scarcely matters, you so do not want to Google it. A skinny type in a red alien spider outfit with one leg (the outfit, not the skinny type – but see later) screamed at us a bit and a keyboardist hung backwards from his instrument. The skinny type intoned, “We’re so happy we could die”. There was a pyramid. That was the level of it. The skinny type did have Bowie tones to his voice and it wasn’t bad if you like metal, so 1 for the song and 3 Euros, although they don’t deserve it.

LITHUANIA. The only act which we awarded nil points for the song and nil points for the magic Eurovision factor. Is that a win or a fail? Monika Linkyte has a not bad voice which was wasted on a dreary song called “Stay’ and a badly made red frilly dress. She did wear good platforms and kept it all woke with African gospel style singers. Still tho. Dull dull dull.

ISRAEL. The peculiar Noa Kirel mugged her way through the dramatic ditty ‘Unicorn’. Unfortunately, Noa and her (apparently many) supporters were given to making the ‘Loser’ forehead sign, mistaking it for a unicorn horn. More Ariane Grande. “Do you wanna see me dance?” Christ no. But Noa did anyway, on the floor, straight off the pole. Noa is up there with Blanka and Brunette in the would-be sex kitten stakes. Unfortunately her half-closed and wonky eyes made it difficult to distinguish her winking and ‘come hither ‘ looks’ from tics. Voice ok but a bit shrill, so you know how many points we allow for that song. 1 Euro-point for the cargo pants coming off and the plastic underwear.

SLOVENIA. Until we saw Croatia’s entry we didn’t think the Balkan states could get it wronger than this. 5 or 6 mop-top boys dressed and coiffed like the Monkees cavorted around delightfully mugging, winking and casting sexy looks at the camera. They sang, or their name was, Carpe Diem (I really cant care enough to look it up) and they finished with big letters – JOKER OUT. 1 Euro-point for the sheer nastiness of the concept.

CROATIA. Yes, Eurovision, save the best for second to last. Don’t try to tell us that the order is random!! We didn’t come down in the last fake fire rain shower. This one is as bad as it can get and thoroughly deserves its 5 Euro-points because they meant it. Apparently these chaps are a real band with real followers and everything. 5 guys dressed in quasi-military uniforms and marched around large wheels shouting ,”Mama bought a tractor” and “Mama kissed a moron” for our edification. They then tore off their skirts to show us their baggy white underpants. It was discordant, ugly, out of date, bewildering, bizarre, ghastly and pure Eurovision.

UNITED KINGDOM. Mae Muller told us “I Wrote a song” but it must have been quick because she spent ages getting her face photographed and the images blown up as big as Hannah. The song she wrote we’ve already forgotten, although it seemed to wander off into rather poor rap. The dancers in ugly red and black costumes (of course) cavorting in front of huge projections of Mae’s face never will be forgotten at TVC, as long as there are tv adverts for cheap lipstick to remind us. 1 Euro point for Mae’s giant face.

While we waited for the pretend votes to be pretend totted-up they threw more stuff from previous contenders at us in a confused and confusing medley known as “The Liverpool Song Book”. The UK Star Man guy from 2022 (Sam Ryder) cheered us all up a bit with a rousing ditty featuring good-looking people missing body parts and Roger Taylor on drums. A really depressed chap called Mahmood waded through “Imagine” as if he were in a hostage video, which he might have been come to think of it, given how bad a song that already is. Netta, the scary Israeli winner from a few years ago wore spider legs like wings – in fact the only wings of the night! A greasy-haired woman called Sonia slumped on a chair and tried to drown herself in 3 inches of water; reminiscent of Ute Lemper, except miserable. For the finale, Duncan Laurence (he’s Dutch or is that Netherlandish now?) wearing funereal garb, lead the whole solemn crowd (including a white-clad Ukrainian choir) in “You’ll Never walk Alone”, which apparently has something to do with a Liverpuddlian disaster. There were star-lights and staunch looks and everything. Moving? Nup.

Then there was the voting. The jury first. “Hello Liverpool! Thank you for a beautiful evening! Our twelve points go to – OUR NEIGHBOUR!” Then the public vote, which we suspect is largely imaginary. There was suspense, but the favourite won. Sadly, Eurovision 2023 was not a winner. Mostly dull. Mostly harmless. But we’ll be watching next year because it is…irresistible.

[* Contenders this year were certainly strings and silhouettes. Red and black was BIG – but hopefully just a whim. Your thoughts?] [**The car might have been a Nissan Skyline. Or not. Do they have Nissan Skylines in Liverpool? It looked more like one of those cars the 400 new Wiggles or 400 clowns squeeze into – which brought us to the realisation. There were no clowns (of the circus type) in this year’s Eurovision. (Sad face.)] Continue Reading →Jimmy Carr – Terribly Funny

(Thebarton Theatre, 22 April 2023)

For the better part of 2 hours late on Saturday night, comedian Jimmy Carr entertained a packed theatre with his urbane brand of dark, un-PC humour. His promotional statement: “Jimmy’s show contains jokes about all kinds of terrible things. Terrible things that might have affected you or people you know and love. But they’re just jokes – they are not the terrible things.” It takes a certain courage to make jokes about rape, paedophilia, poor parenting, and death, but generally he gets away with it, and he is well onto the next bon mot before some in the crowd have stopped wincing.

In sum, Carr’s act is pure filth. But there is no malice in him, and he is terribly funny. What more can you ask?

Continue Reading →Victor Churchill

(953 High Street, Armadale (Melbourne), April 2023)

Originally opened in 1876 as a butcher shop in Sydney, Victor Churchill eventually expanded to Melbourne; specifically, Armadale, to which TVC Ubër-ed in the pouring rain. Featuring an artisan butchery and grocer, we came for dinner, at the curved marble dining counter.

This is the place for former President George W. Bush (“I’m a meat guy”), but there are plenty of nice alternatives, including one of our starters, delicious oysters naturale with caviar, trimmings, and lemon.

TVC’s ‘meat guy’, meanwhile, channelled W’s successor (entering Air Force One, he said “Let’s see how you guys do a burger”) and savoured a classic standard, Steak Frites with black market flank steak – sublime.

Wine and service excellent. Not far out of the CBD, Victor Churchill Melbourne is a must stop for hungry carnivores.

Continue Reading →Triangle of Sadness

(writer and director Ruben Östlund) (2022, Foxtel)

In the 1988 movie Funny Farm, hapless writer Andy Farmer (Chevy Chase) is asked whether his novel in progress is comedy, action or adventure. He replies, gleefully: “It’s all three”. Triangle of Sadness is a dreadful melange too and there’s nothing to be gleeful about. It’s a bore. Östlund didn’t know if he was making a gross-out, social satire, or survival movie. It is, in fact, a poorly executed scramble of all three, mixed with a bit of luxury yacht-and-model-porn. Östlund puts a stereotypical bunch of wealthy cruise-goers on board the SS Minnow – sorry, an unnamed yacht – and jabs madly at them with the blunted, worn-out spears of the woke left. The uber-rich can be lecherous, dumb, spoilt and unaware. Who knew! Other people have to serve them. Who knew! They can even be evil, as are the charming elderly British couple (subtly named Clementine and Winston) who turn out to be arms manufacturers. The only vaguely amusing parts of the yacht scenes are provided by Woody Harrelson as the perpetually drunk captain listing to starboard [Shades of Captain Ron? – Ed.].

There is no amusement at all, however in the exchange between the captain and and a Russian oligarch, Dimitry (an excellent Zlatko Burić) of boilerplate capitalism v communism cliches – (Russian oligarchs can be capitalists. Who knew!) – unless it is guessing which tired maxim comes next. Dimitry, by the way, finds it amusing to answer the question, “how did you make your money?” by barking “I sell shit!” then laughingly confirming that he means fertiliser. Still, Dimity is kind of likeable and believable. One of the few, including stroke-victim Therese, (Iris Berben) who conveys the dreadful frustration of being unable to speak with poignancy. Would that some of the other characters chose to remain mute.

The yacht hits a storm while the guests are eating peculiar but posh seafood dishes (of course). A torrent of projectile vomiting, that would disgust both Peter Greenaway and Mr. Creosote, begins. Dimitry’s mistress rolls about in a vomit covered bathroom – apparently her punishment for coming on the cruise with her boyfriend and his wife. Never forget that this is a morality tale. No, don’t worry, you won’t be allowed to forget.

This onboard middle part of the film is pointlessly preceded by a Zoolander-like story of the unhappy relationship between two models – the perpetually confused Carl (Harris Dickinson) and his unpleasant girlfriend Yaya (the late Charlbi Dean). It might be that Carl is as mystified as we are that the drawn-out argument about which of them should pay for dinner is in this movie at all. Or why he had to ponce about at a modelling audition first.

There are pirates and a hand-grenade (the irony). The SS Minnow (sorry, did it again) goes down and some of our cast of haves and have-nots end up on a tropical island still in their class-indicative, clean and pressed clothes. “Now!” says our social justice warrior director, “we’ll turn the tables. Those who were up are now down. And so on”. [Shades of Lord of the Flies? – Ed.] Abigail, (the excellent Dolly de Leon) a cleaner on the yacht, becomes the island leader. “I caught the fish. I made the fire. I cooked”. At that point, astonishingly, the term, “the means of production” is actually used.

The film looks marvellous, but the soundtrack is a horror. The music, storm and beach sound effects are mixed so loudly that dialogue can be hard to hear. And the eating noises! Why do sound guys love the unnatural slurping and chewing sounds they invent using vacuums and toilet plungers, or something?

Finally, Yaya and Abigail go searching and find something which is no surprise to the viewer, but the very ending, might be. It must have been written in one of Östlund’s ever so slightly more imaginative, less preachy moments.

It’s not that Triangle of Sadness loses its way. It meanders heavily on its own confused but virtuous path, braying at the audience. It’s a righteous donkey. But don’t watch it if you like donkeys. The donkey on the island suffers a worse fate than the donkey buried on the Farmers’ property [Shades of The Banshees of Inisherin? – Ed.]. Watch Funny Farm instead. Or Lord of the Flies. Or Gilligan’s Island.

Continue Reading →Rice Paper Scissors

(15 Hardware Lane, Melbourne, April 2023)

It’s a little funky, a little trendy, dare we say? – a little woke, but while Rice Paper Scrs staff shoot from the hip, they are hip when they shoot. It’s a great lunch place, roughly on the edge of Melbourne’s Chinatown, but the grub is more a fusion of east and west – and it is terrific.

We started with some tasty cocktails, and then moved onto a nice Melbourne riesling, to wash down a Thai Prawn roll (a brioche bun stuffed with poached prawn salad, makrut lime mayo, sriracha and yarra valley smoked salmon caviar); Mushroom Dumplings (local mushrooms, lemongrass and garlic. served in tom kha sauce and chilli oil); a massive Thai Fried Chicken (marinated in ginger, garlic, chilli and lemongrass. served with sriracha mayonnaise); Sticky Soy Tofu; and the highlight, a signature dish, BBQ Lamb Ribs (marinated lamb ribs in a sticky mekhong whiskey glaze, melting off the bones).

By the time our salad did not arrive, we didn’t need it. Diners are encouraged but not dragooned to share, and the dishes are good for that. Staff very friendly but we got there early, and they were under the pump from about 12.30 pm – the joint was chock full by then, with a queue outside. Well worth a visit (we recommend booking).

Can You Ever Forgive Me?

(Directed by Marielle Heller, 2018)

We were familiar with Ms. Heller’s work through that deceptively small film, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, and here, as there, she clearly is the Goddess of Small Things, able to turn an interior work into something a bit special.

The story is ‘sort-of-true.’ Worthy but down-and-out and written-out journeyman writer, Lee Israel (Melissa McCarthy, who was in the terrific comedy Bridesmaids) has rent and bills past due, can’t keep a job because of poor interpersonal skills, can’t afford veterinary treatment for her cat, Jersey, has a drinking problem, and an agent (Jane Curtin, in a superb performance) who is as calculating as Bebe Glazer in “Frasier,” and as remote and uninterested as Withnail’s agent.

Lee’s forte is biography (which should have grounded her sufficiently in the value of prime-source documents, but let that pass). Near the end of her tether, she finds an old letter from Fanny Brice wedged in a book on the famous Funny Girl, adds a personal and salty flourish to it on an old typewriter, and discovers that the lucrative memorabilia market is slightly sloppy in matters of provenance. So begins her career as a forger, in which she is joined by unreliable partner, gadabout and and drinking buddy, Jack Hock (Richard E. Grant).

This could have flopped, big time. After all, the story is wafer-thin and plays like a morality-tale free from moral restraint. But it succeeds, thanks to the sure but light directorial touch, and lovely performances, particularly by McCarthy and Grant. Grant is all louche charm – sleazy, boyish, transient, insouciant, soused and enthusiastically gay. McCarthy does great serious-comedic work as a frump and a grump with inner resources she had forgotten, and an awkwardness she is determined not to shed. The two make a fine pair of rogues and then, when all falls apart, a bittersweet brace of riffraff, up there (or down there) with Withnail & I or Ratso Rizzo and Joe Buck. We also liked “Towne” (the beloved cat), and the opportunity to re-visit Argosy Books (metaphorically).

“What’s my name today?”

KIIN

Kiin, Modern Asian Dining, 73 Angas Street, Adelaide, 22 March 2023

Kiin (Thai for ‘eat’) is Adelaide’s newest Thai restaurant, with a modern (‘fusion’?) menu amid understated but tasteful and comfortable surroundings. It is just up from the court precinct, so if you don’t mind dining amid lawyers, there’ll be no problem. TVC visited one mild Autumn night, and were enchanted – nay, dazzled – by a very funky bill of fare.

We had: A BBQ Chicken thigh skewer, smoked and served in a light yellow curry, which was fragrant and full of heat;

A lychee prawn pop popper (pop in the mouth for a fizzing heavenly explosion) – see below:

The oyster was dressed with angels’ tears;

A White peach ‘som tum’ salad had, tomato, chilli, peanuts, pear;

Stir-fried rice cakes, ‘pad prik king’, pork crackle, with herbs and

a very modern take on a Chicken Maryland dish (no battered banana and pineapple fritters here!)…washed down with:

Pol Roger ‘Brut’, a good Chenin Blanc, and a Pierre-Marie Chermette Beaujolais.

TVC had a minor quibble about an aspect of one dish – a higher-up dealt with it with a courtesy that is rare these days.

TOP MARKS!

[UPDATE: We returned to Kiin on 6 October 2023, a Friday night and the joint was jumping. Kiin hasn’t kept to its previous high standard: it has got even better. Service still impeccable – signature dishes superb, and some great new creations to savour on offer. We re-visited the Local oyster, Bloody Mary, chilli oil, shallot and sublime Prawn and lychee pop stick, chilli sugar-salt; and tried the salad of Watermelon, mint, celery, prawn floss, toasted rice, tamarind, roasted chilli; terrific. Hot n’ crispy fried chicken ribs, three chilli sauce, lime – yum. And they produced the best “slider” in our experience – Red curry cheeseburger, crispy onion, Provolone, ketsup.Kin dī !! (Eat Well).]