The Varnished Culture's Thumbnail Reviews

Regularly added bite-sized reviews about Literature, Art, Music & Film.

Voltaire said the secret of being boring is to say everything.

We do not wish to say everything or see everything; life, though long is too short for that.

We hope you take these little syntheses in the spirit of shared enthusiasm.

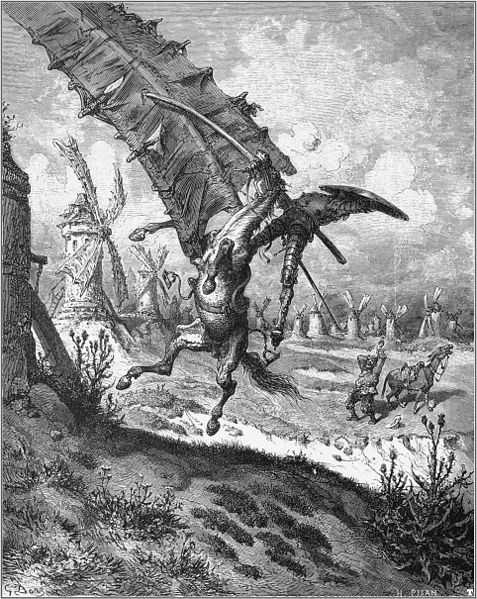

Don Quixote

(Miguel De Cervantes) (1605 -15)

The man of La Mancha is somewhat akin to Walter Mitty, braver and with dementia. A proud and hapless dreamer, he is perhaps rather the inverse of Mitty (a modest man who dreamed of himself as doing great feats) in doing silly things and imagining them as great. Not just silly, mind – proud and uncanny – some of his acts verge on the psychotic.

Idealised as the first ‘modern’ novel, arguably post-modern, reading it today, you start to feel as mad as the faux knight after working through the artless courtly romances of his time. A minor noble ‘behaves his way to success’ (pace Dr Phil McGraw) and sadly regains sanity after a life of failure. The Don’s Rocinante is an exhausted, exhausting, one-trick pony, staggering through a myriad episodes on a brace + 1 of overlong road trips. After 900 pages, you need a blood transfusion.

The book reflects the cruelty abroad in Spain. After a pogram (circa 12C and early 13C), Jews ‘encouraged’ to become Christians (“conversos”) were suspected of backsliding or crypto-worship and that lovely couple, Ferdinand and Isabella, instituted the Inquisition to weed out the enemy within. By the time Cervantes was writing, the Moorish converts (“moriscos”) were being crushed as well. Cervantes’ novel tags the Holy Brotherhood as a bunch of thugs but steers clear of the Holy Office. The only ‘inquisition’ is the pleasant one in Quixote’s library.

But the book doesn’t play safe – it contains so many lush absurdities as to be subversive, its hero’s catalogue of failings funny in an arctic way. Pass by the dominating windmill and the wrecked puppet show and take one modest example – the Don sends Sancho into town to pass on his affection for Dulcinea but she can’t be found (unsurprisingly, as neither know what she looks like). Judged only by their actions, this famous pair are morons. But they win our weary attention because their hearts are in the right approximate place. In our enlightened age, we’d not put the knight errant in a cage, but get him and his squire on Thorazine. But they are probably not apt for such treatment because for them, reality is a placebo. They will not swallow it.

Quixote is better known than read. Part of this is due to its length, its veneration by previous generations, its powerful motifs, and the popular musical written in the 1960s, filmed in 1972 with Peter O’Toole, James Coco and Sophia Loren, a $12m flop filmed on “the most depressing sets that ever existed.” [O’Toole, quoted in The Hollywood Hall of Shame, Medved Bros. (1984)]

There was a 400th anniversary celebration, for Part I, in Spain (where the book is venerated) and doubtless it will be a good place to be again this year.

Cervantes died on April 22, 1616 (a day before or perhaps the same day as Shakespeare) and was believed buried at the crypt at the Convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians, Madrid. Humour is subjective and ephemeral but he would have laughed at the recent fuss over his alleged bones. “For blood is inherited but virtue acquired, and virtue has an intrinsic worth, which blood has not.”*

[*J.M. Cohen translation] Continue Reading →The Marriage of Figaro

(State Opera SA, 2008)

Mozart takes an imperial opera buffa and outdoes Rossini, no mean feat. As directed by Neil Armfield, the sense of the composer’s wickedness is retained, with slight sets that actually add rather than detract. As the triumphant underlings, Figaro and Susanna, David Thelander and Teresa La Rocca make a lovely couple and were in fine form. Based on the subversive book by Beaumarchais, Mozart manages (apparently without effort) to give his frantic entrances and exits a hard edge. A great piece, worth seeing anytime – here done very well indeed.

Continue Reading →

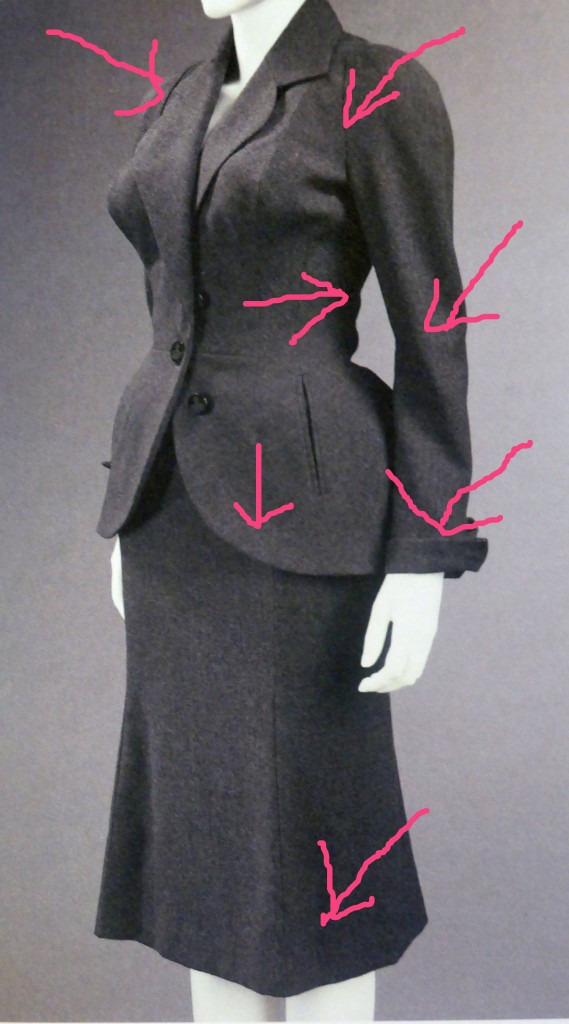

Vivienne Westwood

(by Vivienne Westwood and Ian Kelly)

It is no secret that, ever since I read “From A to Biba” and “Quant by Quant”, there has been a special place in my daydreams for an assuredly idealised and somewhat chronologically inaccurate 1970s King’s Road, London. I’ve often imagined bobbing into Biba for some knee-boots and popping into Mary Quant for some pop-art makeup*. But until I read this bio/auto-bio, I never, but never, envisaged wandering into Dame Vivienne’s “Worlds End” store on that same blue-skyed Saturday morning. Perhaps because it is in such a different world altogether from the non-challenging swinging London I have always imagined. I really didn’t know that it (and its predecessors, “SEX” for one had even existed. Punk had shops? Who knew?). “Vivienne Westwood” by the woman herself and a journalist who doesn’t seem to have any real interest in fashion has set me right. The book is not great literature – the writing is clunky and not fully synthesised – Westwood’s lengthy quotes are strung together with some breathless praise (and McLaren bashing). I could have done with more about the process of design and more details about the actual — err — clothes, but if you are at all interested in fashion, twentieth-century London, punk or that sort of thing, this is a must-read. (But skip the last rather preachy couple of chapters). Mrs Westwood has apparently never suffered from a moment’s self-doubt or uncertainty about her own talent or peerless moral goodness which makes for an invigorating read but at times some rather dodgy product and an inconsistent human.

EXHIBIT A

My mother was an exacting dressmaker. Although she has been embroidering angels’ robes while watching previously unseen episodes of “The House of Eliot” for about six months, I can hear her shouting from here about this “tailored’ Metropole suit from the Westwood Label. Not that you need it, but I have helpfully pointed out the worst bits.

EXHIBIT B

There’s just something wrong with them.

EXHIBIT C

They look wonderful….

Until an actual woman puts them on….

But there are the shoes…..perfect.

*(In fact I have a genuine Quant lipstick – silver white with the palest pink wash, now also tinged with green from age. Although it came from David Jones, Rundle Mall and wasn’t sold to me by a Twiggy look-alike, I can’t throw it out).

Continue Reading →

Incitement

Julius Caesar

(1601) (Dir. Joseph L. Mankiewicz, 1953)

A good film of a great play, scribbled when Shakespeare was limbering up and entering his white hot phase. The story is mainly of Brutus, nicely and very glumly played by James Mason as the ‘reluctant’ conspirator. All of the key players are good, although one might say Louis Calhern plays Caesar much like he was as the big spy boss in Notorious (that playing strangely fits the minor but key part in the play but is much too vigorous for a 66 year old prone to fainting spells). Suetonius called Caesar “deified” and suggested that he was a notorious philanderer (his soldiers sang of him as ‘the bald adulterer’) including of Servilia, the mother of Brutus. This is not made explicit in the play or the film but it might tend to explain the ambivalence of Brutus. John Gielgud as Cassius has a more straightforward role but his intensity is just right.

The revelation is Marlon Brando as Mark Anthony. Though he has a famous set piece, the funeral oration for Caesar to the citizens, he is nevertheless on the play’s margin, compared to Brutus. Yet Brando manages to show the fear, anger and rat cunning of Anthony, who is, after all, a political animal par excellence. You can see how crafty he is in dealing with the conspirators after the murder – with anxiety, respect and supplication, that soon turns to open hostility and incitement when he gets his moment to sway the mob. As he turns and leaves them, now baying for the blood of the assassins, you can see a small fox smile – as if to say ‘that is very neatly done’, which it was. Apparently there was some small controversy at the time over his casting – perhaps some feared a Stanley Kowalski style speech to the Romans. But it is a strong but subtle turn.

Julius Caesar has some great lines:

Julius Caesar has some great lines:

“Beware the ides of March.”

“The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, But in ourselves, that we are underlings.”

“Yond Cassius has a lean and hungry look; He thinks too much: such men are dangerous.”

“And, since the quarrel Will bear no colour for the thing he is, Fashion it thus; that what he is, augmented, Would run to these and these extremities…”

“Cowards die many times before their deaths; The valiant never taste of death but once.”

“If I could pray to move, prayers would move me: But I am constant as the northern star…”

“O, pardon me, thou bleeding piece of earth, That I am meek and gentle with these butchers!”

“Cry ‘Havoc,’ and let slip the dogs of war…”

“I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. The evil that men do lives after them; The good is oft interred with their bones.”

“I fear I wrong the honourable men Whose daggers have stabb’d Caesar; I do fear it.”

“This was the most unkindest cut of all…”

“Fortune is merry, And in this mood will give us anything.”

“Fortune is merry, And in this mood will give us anything.”

“There is a tide in the affairs of men, Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune…”

“I draw a sword against conspirators; When think you that the sword goes up again?”

“This was the noblest Roman of them all: All the conspirators save only he Did that they did in envy of great Caesar”

TVC deducts one star because the swords simply didn’t look sharp enough…et tu, props?

Continue Reading →

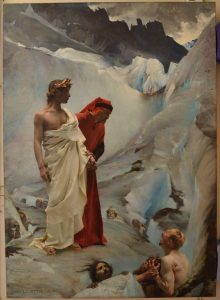

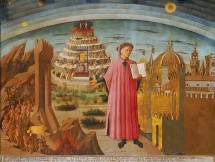

Divina Commedia

(by Dante Alighieri 1/6/1265 – 14/9/1321) (completed 1320)

[Note: extracts are from, and reference is to, the John Ciardi translation]The greatest epic poem of all time (and we can say this with confidence, despite the dodgy standard of TVC’s latin).

It has a brilliantly (classically) simple structure – Recounting, in terza rima, how Dante spends the 1300 Easter vacation on a salvational tour of the worlds of our minds (and souls), guided through Hell and Purgatory by his poetic mentor, Virgil and accompanied by his poster-girl, Beatrice, in Paradise. There they meet Dante’s fiamma benedetta a flame of heavenly wisdom, S. Thomas Aquinas. S. Thomas was a formidable thinker but no great writer. Dante, taking hold of the 13th C theologian, supplied the art. “it is the flame, eternally elated, of Siger, who along the Street of Straws syllogized truths for which he would be hated.” (Pa. X) But he did something more: he created a new universe. And it was a universe that left Aquinas and Augustine, the best of the ancient Christians, pounding in the wake of something strange and monolithically modern. As Harold Bloom said with his usual wisdom in The Western Canon, “The Comedy…destroys the distinction between sacred and secular writing.”

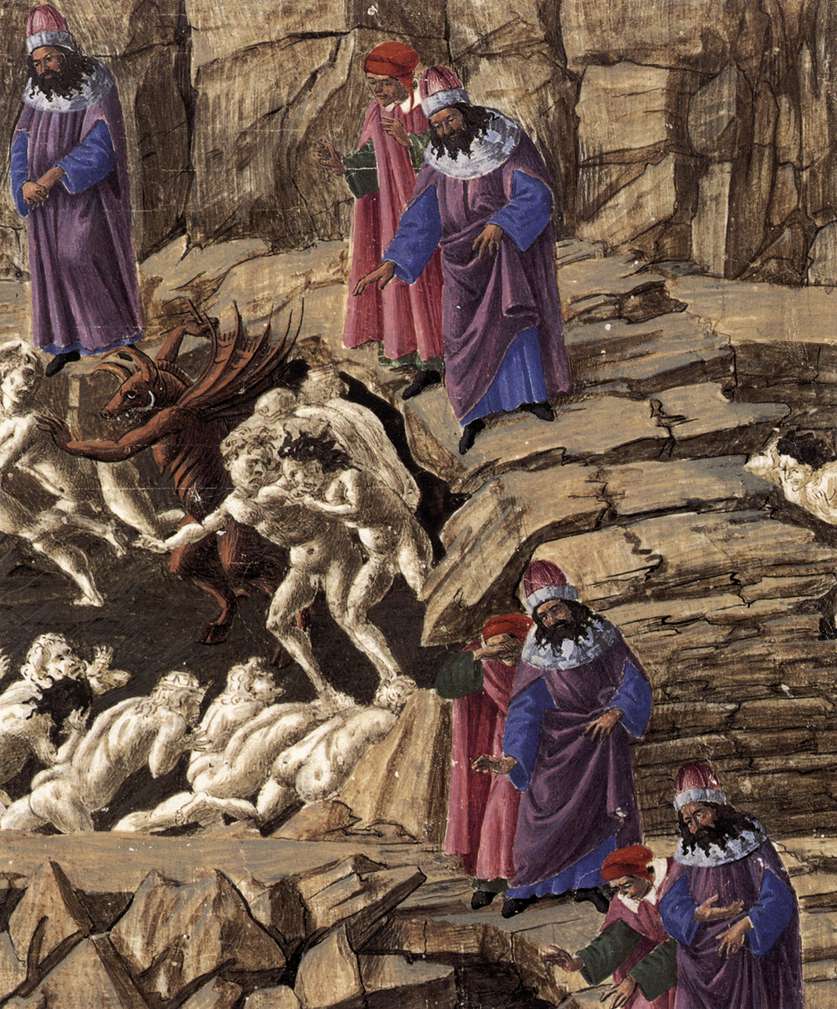

One of Sandro Botticelli’s drawings for Divina Commedia

The Comedy is the product of a literary magpie. Dante’s beak dips into scripture, classical pagan writing, European politics, local and familial affairs. The result of this accumulative density is a tower to house a Dante industry, a tower the height and volume beside which James Joyce Inc. pales into a noon shadow.*

There is a very medieval pattern of symmetrical numbers: we follow the nine circles of Hell, and then say “Hi” to Satan; ascend the nine rings of Mount Purgatory, then, washed clean of sin and ignorance, loiter in Eden and float about the nine celestial spheres before entering the Empyrean and regarding the mystic rose, the kind of trope Guillaume de Lorris wrote about, circa 1237. Ultimately, Dante rests after his work’s outing, musing on Paradise that “…already I could feel my being turned – instinct and intellect balanced equally as in a wheel whose motion nothing jars- by the Love that moves the Sun and the other stars.”

Dante used this gigantic, preternatural road trip to see scores settled, of course: indeed, it constitutes something of a revenger’s fable on the Ghibellines and Pope Boniface VIII, conceived on a titanic scale.

It is the perfection of brevity with which Dante encapsulates difficult and large matters. Take, for example, his (as it were) temporal depiction of the timeless:

“Nor did He lie asleep before the Word sounded above these waters: ‘before’ and ‘after’ did not exist until His voice was heard.” (Pa. XXIX)

Or this precursor to C.S. Lewis; “The double grief of a lost bliss is to recall its happy hour in pain.” (Inf. V)

“nor can we admit the possibility of repenting a thing at the same time it is willed, for the two acts are contradictory.'” (Inf. XXVII)

Or this paradisiacal arbitrariness: “…the Supreme light fittingly makes fair its aureole by granting them their graces according to the color of their hair. Thus through no merit of their works and days they are assigned their varying degrees by variance only in original grace.” (Pa. XXXII)

Dante was only aged 9 when he first saw Beatrice, “the woman whom my mind beholds in glory…” In Purgatory, Beatrice does not so much replace Virgil as allow Dante to supplant Virgil. Whereas the great and the almost good revere Virgil (e.g. Sordello kneels before him: Pg. VII), he is the past. B is a super Muse, telling Dante to ‘man up’, ‘dry your eyes, Bono’ and ‘suck it up’. “‘Dante’” she says, naming the great man for the first and only time, “‘do not weep yet, though Virgil goes….Did you not know that here man lives in bliss?’”

“Hey, good lookin'” (painting by Henry Holiday)

It is chilling to consider literary fashion. There really ought to be no such concept. Yet, as J. B. Priestley reminds us in Literature and Western Man (1960), “…the enlightened age of Voltaire looked down on Homer and Dante and regarded Shakespeare as a clown and a barbarian…”

But Dante Alighieri is secure. His proud shadow falls even on poets who never heard of him.

The influence of Dante’s work is, obviously, immense, too gargantuan and complex to cover here. Just a few examples will serve TVC’s purposes:

Ezra Pound, in Canto XXXVIII, cites Paradiso XIX, concerning debasement of currency. Dante dressed this sin (his charge against Philip of France) as one of a salad; Pound, alas, tended to focus, to an unwholesome degree, on usury and currency speculation.

T.S. Eliot, in The Waste Land, footnotes Inferno III and IV, but his whole poem is drenched in Dante. In his little book on Dante, he observes: “The majority of poems one outgrows and outlives, as one outgrows and outlives the majority of human passions: Dante’s is one of those which one can only just hope to grow up to at the end of life.”

In just about every celestial painting by William Blake, and others, one sees the cantos of Dante.

Osip Mandelstam, during his exile in the Urals, wrote Conversation About Dante. He identified the way Dante loosed his demotic Tuscan on the world and helped clear the way forward. He said this: “The creation of Dante is above all the emergence into the world arena of the Italian language of his day, its emergence as a whole, as a system.” George Steiner, in his difficult but rich book, After Babel, highlights “Mandelstam’s penetrating comment on Dante and on linguistic form [which] echoes his own asphyxia under political terror, in the absence of tomorrow.” Steiner goes on to consider Rudolf Borchardt, who concluded that “Dante’s absence from the history of the German language and of German sensibility in the period 1300-1500 destroyed deep logical and material affinities between German feudalism and the ‘classical’ Christendom of the Provence and of Tuscany.”

Marx and Engels recognized Dante’s power, and hoped to harness it to their political purposes, acknowledging him as the canon of the middle ages. In the preface to the Italian edition of the Communist Manifesto, Engels wrote: “The first capitalist nation was Italy. The close of the feudal Middle Ages, and the opening of the modern capitalist era are marked by a colossal figure: an Italian, Dante, both the last poet of the Middle Ages and the first poet of modern times. Today, as in 1300, a new historical era is approaching. Will Italy give us the new Dante, who will mark the hour of birth of this new, proletarian era?” [No.]

H. W. Longfellow was the first American translator of The Divine Comedy. In his poem, Divina Commedia, he sang: “And the great Rose upon its leaves displays Christ’s Triumph, and the angelic roundelays With splendour upon splendour multiplied: And Beatrice again at Dante’s side No more rebukes, but smiles her words of praise.”

He mesmerized his own generation as well. Vasari notes that Michelangelo “much delighted in readings of the poets in the vulgar tongue, and particularly of Dante, whom he much admired…”

Giotto first met Dante in 1305 and whilst most of his figures in profile look disturbingly like Marlon Brando, this would seem to render the poet aged about 40.

*DANTE’S PEAK: To climb the mountain of works on the Divina Commedia, one might usefully start with two books and their selected bibliographies: The Cambridge Companion to Dante (1993) edited by Rachel Jacoff and Dante and His World (1966) by Thomas Caldecot Chubb. Also see Giovanni Boccaccio, Life of Dante (1374).

Continue Reading →

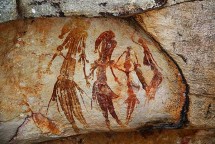

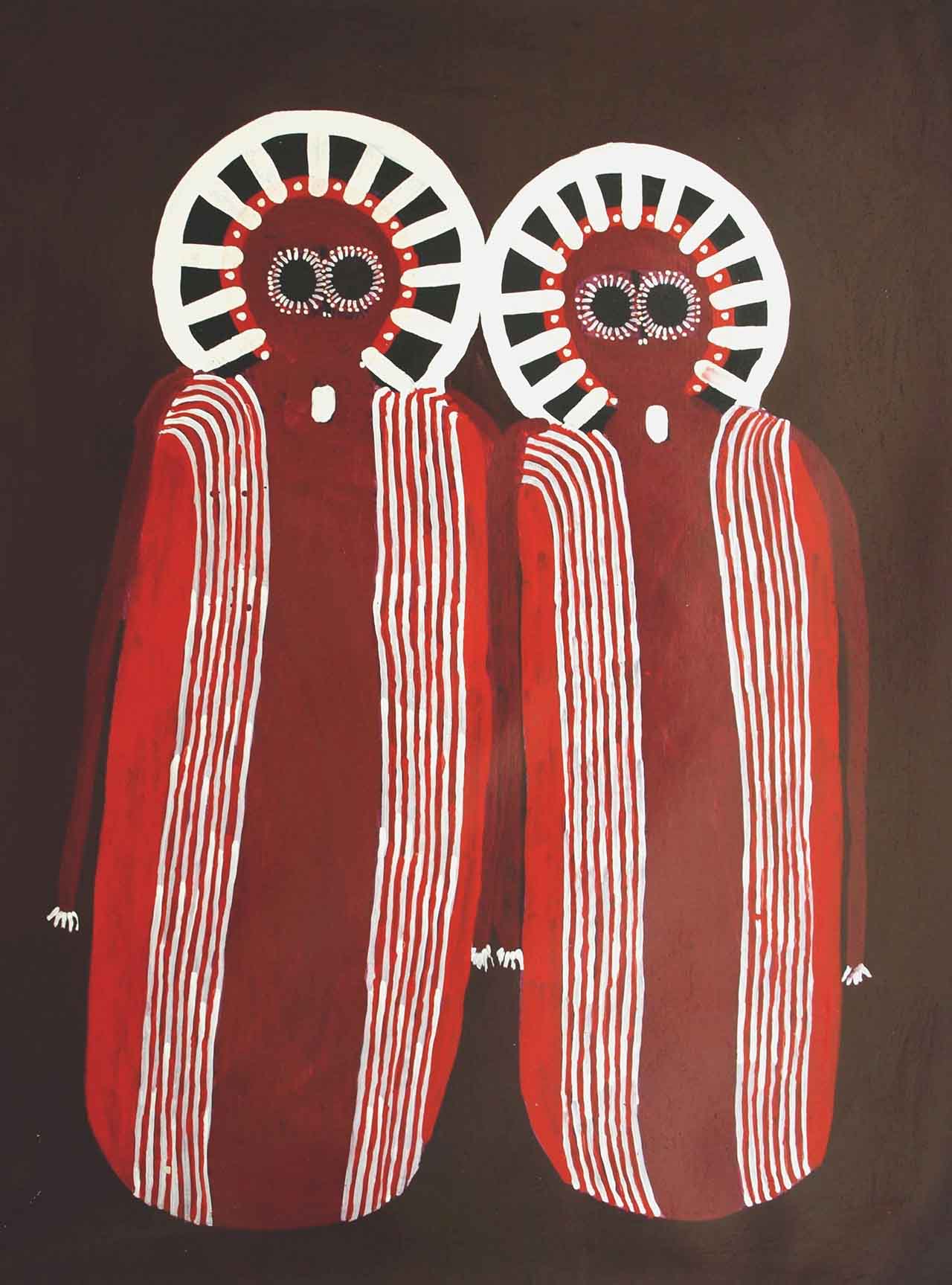

Aboriginal Art

(by Howard Morphy)

A sumptuous, encyclopaedic and expert review of indigenous visual art from ancient to modern times, from representative to decorative to spiritual to political, covering all mediums; yet another beautiful Phaidon addition to the good art libraries. Published in 1998, it could do with a new edition (to cover ‘newbies’ such as the contentious Sally Gabori, 1924-12/2/2015).

By Jack Dale Mengenen

-dreaming.jpg)

Clifford Possum Tjapaltjarri, ‘Love (Sun) Dreaming,’ (1972)

Duel

(Dir. Steven Spielberg) (1971)

TVC’s all-time favourite trucking movie. Even with the padding of additional scenes to lengthen the story for theatrical release after its debut on U.S. television, it is still a masterwork of ruthless economy in its staging, editing and plot. Dennis Weaver is the perfect Mr. Average who plays a little chicken with a foul, evil-looking old rig, and gets a hell of a lot more than he bargained for. Everything hangs together – everything is plausible – the tension is built up seamlessly and then, “there you are: right back in the jungle again.” Spielberg is probably the world’s most famous director of our generation (and deservedly so) but he hasn’t done anything better than this.

Continue Reading →Suddenly Last Summer

Sydney Theatre Company, Opera House, March 2015

A thin story, not as shocking now as it was when Tennessee Williams wrote it, or even when it was filmed in 1959. Presented here as a sort of live cinema – for much of the play the actors are videoed as they perform in a pot-plant garden behind the screen on which the video is shown. Doors and windows open and shut. Robyn Nevin doesn’t really have much to do. Eryn Jean Norvill as Catherine and Mark Leonard Winter as Dr Cukrowicz are impressive. Sebastian’s part is effective and powerful. An odd choice of play for such an inventive presentation.

[Marginal note: P watched the last 20 minutes on closed circuit TV from the bar at the Op House – prima facie, a talkfest in a garden of statuary. Robyn Nevin seemed reduced to reacting from a chair, which she did more happily in The Castle. She deserves better.] Continue Reading →The Buried Giant

(by Kazuo Ishiguro)

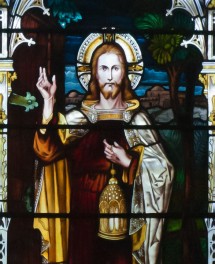

A plodding tale about memory, being nice to one another and Sir Gawain. Fittingly, the dragon who may or may not be the villain of the piece is thin, bloodless and apparently asleep. The plot meanders episodically. The characters Axl and Beatrice are loving and real in their way, but the other characters are indistinguishable. There is no soul, no gravitas, no depth. Is the giant Arthur? or the dog of war? or does it have some eschatological meaning? Either way it stayed well buried.

If one wishes to read about King Arthur’s nephew, try Sir Thomas Malory (picture of the Grail on the Round Table by Évrard d’Espinques, c.1475)

Continue Reading →