The Varnished Culture's Thumbnail Reviews

Regularly added bite-sized reviews about Literature, Art, Music & Film.

Voltaire said the secret of being boring is to say everything.

We do not wish to say everything or see everything; life, though long is too short for that.

We hope you take these little syntheses in the spirit of shared enthusiasm.

‘Nothing Better than the First Attempt’: Cabaret Life Drawing

(Cabaret Life Drawing, Adelaide Cabaret Festival, 11 June 2022)

A very pleasant hour passed in the Cabaret Festival’s Spiegeltent on the Festival Centre Plaza. This was a life drawing session (not really a lesson, more like a brief taste with a light touch). The assembled throng, their creative impulses enlivened by a glass of wine and some piano and bass versions of songs such as Puttin’ on the Ritz, Tea for Two and All of Me, attempted to depict model Letitia, striking various classy poses in an elegant gown (see below).

It was conducted by Adelaide Central School of Art graduate Ruby Chew (below) [BA Visual Arts Hons. at Adelaide Central School of Art (2010), along with further study at Central Saint Martins, London and the Florence Academy of Art, Florence]. Ruby’s work has been accepted into the prestigious Helpmann Academy Graduate Exhibition, where she was awarded the SALA Prize, part funding her first solo exhibition, and the Hill Smith Gallery/Helpmann Academy Travel Prize, funding a 3-month artistic development trip around the UK and Europe.

Ruby has exhibited, taught and held residency positions interstate and overseas. She has had numerous solo exhibitions, notably Portraits at Magazine Gallery (2011), Spitting Image at Hill Smith Gallery (2012) and The Difference Between Things at Floating Goose Studios (2021). Her website is: http://www.rubychew.com/

Ruby ran us through a number of exercises designed to afford amateurs an entrée into the creation of charcoal drawings of the model and her surrounding artefacts. It mattered not that the overall feel was more salon than cabaret club: using charcoal, tissue for shading and a portable board standing-in for an easel, we attempted continuous line drawing, drawing “blind” and using the non-dominant hand (we suppose a property lawyer would call it the ‘servient hand’) to draw, or try to draw, in a fun and relaxed atmosphere.

Near the end of the session, Rosie Russell joined Letitia as an additional model, while she belted out an impressive version of “At Last” with the support of the two excellent musicians.

We can’t say our efforts will be hung in any gallery walls, but this no-pressure workshop was a playful gift and for us, a gentle opener to the Cabaret Festival.

As that talented rogue, Picasso, said, “In drawing, nothing is better than the first attempt.”

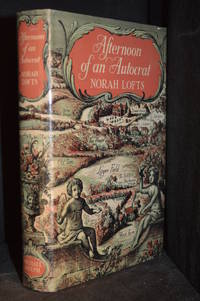

Continue Reading →Afternoon of an Autocrat (Norah Lofts)

Norah Lofts (1904 to 1983), mostly forgotten in this twilight of the gods, was a popular English novelist. Afternoon of an Autocrat *(1956) is set in Suffolk, in the fictitious village of Clevely at the time of its ‘enclosure’. In Britain, thousands of ‘Acts of Enclosure’ were passed between 1604 and 1914. A passel of commissioners, (susceptible to good hospitality, spite and whim) would descend upon a village and delineate how fields and hitherto common lands were to be parcelled out to those with claims evidenced by writing, social superiority, ancient usage or bribery.^

Part One, (“Afternoon of an Autocrat”) makes short work of the stolid squire of Clevely. “On the third Saturday afternoon of October, in the year 1795, Sir Charles Augustus Shelmadine set out on what – though he naturally had no notion of it – was to be his last ride.” When Sir Charles dies, so does the village’s bulwark against enclosure.

Sir Charles’ cold and debauched heir, Richard, succeeds him and in Part Three – “High Noon of a Changeling” – is persuaded by the ‘lisping’ Mr. Montague Ryde Montague to petition for enclosure. “‘I cannot, of course, guawantee that you will do as well out of your enclosure as I did at Gweston,’ he warned. ‘I was deucedly lucky in my commissioners and in the number of fellows who either had no claim to show or couldn’t pay their share of the expenses. Now there is a hint! Don’t twy to keep down expenses.’..”

These kinds of arbitrary land allotment practices led in part to the Torrens Title System of Land Registration which was developed in The Varnished Culture‘s home state of South Australia. It grew out of the confusion and inequity of the recording of land rights in a long and dodgy system of Deeds or scratches on a village milestone. The poor men of Clevely generally cannot prove their claims. “‘Matt Juby dug up a paper, and Amos Greenway…[did spell]…it out for him; and that told how way back his careful old great-great-grandad did get leave from the Squire to build a cottage and graze his beasts…Maybe we all had papers in the past; but you know how it is, sir – folks that can’t read or write don’t set such store by papers as them that can. And there ain’t much space for hoarding such things.'” “‘One chap’d even got his paper – little old black scrap of stuff that was too, and nobody could read it…” “the sort of thing we all had, no doubt, till some silly young bitch used ’em as hair curlers...”

Any lucky villager allotted land must pay a fee and fence the land at his or her cost within a certain period of time, or forfeit the land. Those who thus acquired a landholding which had previously been divided into a number of small pieces of land usually prospered. Others, such as the paupers in the ‘hovels’ of Clevely, now denied the use of ‘The Waste’, were left with the use of the land between the highway adjacent to their dilapidated cottages and the fence immediately behind them, making the tilling of land for potatoes or the feeding of livestock impossible. So they left and sought work, or fell upon the miserable charity of the parish.

Lofts has an acute psychological sense and an unsparing eye which she uses to create demented rich woman, ill-used wife and religious maniac alike. There is an unnecessary supernatural overlay concerning a young woman, Damask Greenway, who takes revenge upon the young man who jilted her, Mithraic rites and a man who (through a Faustian bargain) can neither divest himself of good luck, or die. “‘But to return to Mundford, the sight of him makes me expectorate – he must be hard on eighty; and yet he doesn’t look it, does he?’ ‘So perhaps the rumours are right. He always wins; he does not grow old…'”

The interest in this story lies in the individual villagers, who are (until perhaps a final soft landing) spared none of Loft’s unsentimental assessment or the indifference of fate while stumbling through the desperate issues of poverty and the interplay across generations of meanness, generosity, misunderstanding, old loves and enmities.**

Norah Lofts

Six the Musical

(Her Majesty’s Theatre, 27 May 2022)

Six the Musical, a pop music retelling of the story of the wives of Henry the Eighth of England was royally received in London, New York and Sydney. We are pleased to say that the Adelaide audience loved it just as much as Henry VIII adored Anne Boleyn, and not just at the beginning of it all. The capacity crowd cheered when the six wives appeared in a London pea-souper of dry ice mist and they were on their feet dancing when the queens gloriously asserted their individuality and agency at the end of the 75 minute feminist joy fest.

Wisely, the obvious comparison to Tudor Spice Girls and the old mnemonic “Divorced, beheaded, died…divorced, beheaded, survived,” were got out of the way early on. Each of the unfortunate women sang a solo number – unapologetic in the case of the famously ambitious Anne Boleyn and melancholy in the case of the softer Jane Seymour who died in childbirth. Best though were the numbers when all six joined in – exuberant, on-key and energetic.

The small stage of Her Majesty’s Theatre (or should that be Her Majesties’ Theatre?) – closed for years in order to be renovated to look exactly the same, right down to the inconvenient foyer – was adorned only with with cathedral shaped “windows”, thus putting all the emphasis on the performers and their costumes. These Tudor-meets-jazz-ballet costumes were, in part, perhaps a letdown. The skirts worn by Anne Boleyn (Kala Gare) and in particular, Jane Seymour (Loren Hunter) were oddly proportioned and unflattering. Katherine Howard (Chelsea Dawson) though, all in pink, was appropriately sexy as she reminded us that Anne Boleyn was not the only one who lost her head due to (apparent) adultery.

Catherine of Aragorn (Phoenix Jackson Mendoza) was the most Tudor, pearl-studded and glamorous as befits perhaps the only legitimate queen. Anne of Cleves (Kiane Daniele) was made to look peculiar and unattractive in accordance with her reputation. Catherine Parr (Vidya Makan) (the survivor) was decked in an oddly modern jumpsuit and virtually crownless.

This show is not for those wishing to perfect their knowledge of English history: it reinforces the clichés in an anachronistically and manipulative modern light, but it does enliven our understanding of these 16th century historical figures as real people. In an imaginative coda the women talk about what they might have been, had they not caught the cruel eye of a lascivious and inconstant monarch. No man appears on stage to dim their light – no Henry, no Wolseley, no Cromwell, no Pope. The most excellent band is all female.

Flower Drum Endures – Thank God

(17 Market Lane, Melbourne) May, 2022

Mrs. Appleyard says to Mademoiselle in Picnic at Hanging Rock that Bournemouth was “a delightful place. Nothing changed…ever!”

The Varnished Culture says the same for Flower Drum, tucked away in the heart of Melbourne, just off Bourke Street. We have been coming here for years, whenever commitments bring us to Melbourne. Melbourne has become problematic. Its great high style now looks like Srebrenica after the Serbs finished with it, or Paris churches after the Jacobins. A smoking ruin of a one-party state, where everyone is tolerant of lies, the citizenry does not expect government corruption but demands it, tribalism spills out far beyond the MCG, and totalitarian rule advances with a smiley face, it is ironic that a Chinese institution stands firm, and almost alone, against the barbarians. Indeed, the Chief Barbarian is said to do many of his deals here.

The atmosphere is impeccable. The waiting staff, better dressed than most customers, are magnificent. The food and cellar are superb. We add a star from our last review, recognising that quality and consistency in these troubled times is to be cherished.

We had, after some champagne to whet the appetite:

A Sauté Crayfish Omelette that was divinely fluffy; a lovely Quail Sang Choi Bao with Chinese pork sausage, onions, spring onion, water chestnut and bamboo shoots (iceberg lettuce cup, thank heavens); a Seafood Dumpling Soup; and of course, the classic Peking Duck, each pancake individually wrapped for the diner and served with an artistically arranged plum sauce (see below). Some home made ice cream to share for dessert. All washed down with a couple of bottles of Petaluma Riesling.

The staff do not regard the menu as sacrosanct – special requests are no problem. The wine list is dazzling but there are bargains to be found.

Make sure you book, because the place fills up fast. We arrived early for Monday lunch service but were soon joined by a large cohort of diners, including some very impressively attired Chinese-Australians, obviously regulars.

[2023 UPDATE: TVC attended Flower Drum in April and are pleased to report that it remains the best Chinese Restaurant in the World.] Continue Reading →Lohengrin

(Melbourne Arts Theatre, 21 May 2022)

Lohengrin marked the end of Wagner’s ‘first phase’ and remains one of his loveliest operas, in musical terms (the overture alone is a gorgeous amuse-bouche)*. The story is, of course, very silly: Elsa (Emily Magee) is accused of doing away with her brother, heir to the Throne of Brabant, the charges levelled by nasty Telramund and his ‘handler,’ Ortrud (the very fine and sexy Simon Meadows and Elena Gabouri). King Heinrich (Daniel Sumegi) calls for divine intervention, and after some nervous foot-shuffling by the assembled knights, there, in a puff of swan feathers, is “X” (Jonas Kaufmann) to engage in battle with Telramund to answer the charge.

After that, it is a matter of the thwarted villains’ plan to disrupt the nuptials and jump the inheritance queue to the throne. Meanwhile, the marriage between X and Elsa is imperilled by X’s Michael Corleone-like refusal to have Elsa ask him about his business, or even his name, which seems to us somewhat arch – even Kaufmann has objected that “Elsa’s not ready to go to bed with a guy whose name she doesn’t even know!” In the event, the hero triumphs, but at the last, curiosity kills the cat.

It is a great cast. We found Gabouri and Meadows fashionable jet-black yet oddly sympathetic bad guys, in great voice and cutting a fine dash; Magee’s Elsa was terrific; though Sumegi, and Warwick Fyfe as the Herald (see below), have little to do, they were suitably magisterial with their booming bass voices. The Opera Australia chorus were in peak form, somehow managing to finesse the clichéd wedding march into a thing of beauty. The Orchestra Victoria (including some impressive heraldic brass in the theatre boxes) under a relatively inexperienced Tahu Matheson, were impeccable. In particular, he and they generously made way for the star of the show, Kaufmann, to soar above the pit without forcing his voice on us – thus managing to retain the precious harmonies of the score by signing pianissimo in extended fashion. It was a real treat to see this Opera Rock Star in a full opera finally, after his wonderful concertized Parsifal in Sydney previously.

As usual, and increasingly these days, The Varnished Culture had quibbles with the mise en scène. Much of the time this managed to keep out of the way, yet it intruded jarringly at times. It was a Regietheater conceit of Olivier Py, originated at the Théâtre Royal De La Monnaie in Brussels, and featured some harmless anachronisms: the sets were to represent ruined post WWII Berlin, including a stopped clock set at five past twelve (‘Zero Hour’ in 1945). The three-tiered wall of bric-a-brac (see top image above) was meant to convey German cultural heritage** – including signage bearing such names as Goethe, C.D. Friedrich, Hegel, Schiller, Heine etc., perhaps a deliberate contrast to the anonymity of the protagonist. During the extended Act III tête-à-tête between Lohengrin and Elsa, the pair wended their way up the stairs of this structure, singing sweetly to each other. All very well to this correspondent, sitting smugly in the first row of the Circle, but a friend with a much better eye and ear in the top tier reports that their voices were muffled and their bodies virtually invisible, drowned in the glare of the surtitles board and Opera Australia electronic badging. Shows that you must rehearse properly. Especially at these prices.

Moreover, there were the usual grab-bag of dopey flourishes. A small boy wandered around, toying with a crown seemingly made of brown butcher’s paper (that’ll be Gottfried, we guess). Lohengrin formally appears, on Shanks’ pony, fiddling with a small mound of ‘swan’ down. Why the Herald lollygags about, taking camera snaps, is beyond us. The duel to clear Elsa’s name is rendered by a chess game and some calisthenics at the rear (we would have preferred an old-fashioned sword-fight, even with clock hands). Similarly, we could have done without the gymnastic Chippendale showing off his pecs in Act III.

“Be All That As It May,” Lohengrin was still a treat. The matinee we attended was highly and deservedly enthusiastic at curtain.

![Opera Australia: Lohengrin review [Melbourne 2022] – Man in Chair](https://simonparrismaninchair.files.wordpress.com/2022/05/lohengrin-opera-australia-warwick-fyfe.jpg)

The Dying Citizen

(By Victor Davis Hanson) (2021)

This is a thought-provoking argument that the classical concept of citizenship (the essence of a democratic nation) as developed and refined from the Greeks, Romans, and ‘aristocratic’ revolutionaries, is becoming denuded of meaning or relevance, and that a new tribalism (subject to a new “balkanized spoils system“) is fast replacing it, per the convenience of the governing elites (on the divide-and-rule paradigm). The author ranges wide but without attenuation, contrasting citizens with peasants (we prefer the more colouful term ‘peons’), residents and tribes, and then showing how the very concept of American citizenship – necessary in a diverse nation of 350 million people – is fast fraying; due to the permanent state of unelected bureaucrats, governing elites that treat the citizenry as roadkill on the golden highway to utopia, and, on a higher and more abstract level, the rise of (in practice, totalitarian) globalisation. As Lionel Shriver, with reference to this book, put it*; “Globalisation, mass unassimilated immigration and the left’s cultivation of self-disgust have steadily turned us into mere residents, with no fervent commitment to a shared culture and past.”

“In The Dying Citizen, Hanson outlines the historical forces that led to this crisis. The evisceration of the middle class and the rise of inequality have made many Americans dependent on the federal government…open borders and the elite concept of “global citizenship” have rendered meaningless the idea of allegiance to a particular place…identity politics have eradicated the idea of a collective civic sense of self. A vastly expanded bureaucracy has overwhelmed the power of elected officials, thereby destroying the sovereign power of the citizen.”**

Some examples from the book:

“Simply put, corporate America wanted cheap imported labor without the bother of unionization. Hand in glove with business, the progressive Left agreed with virtual open borders. Progressives assumed either that massive influxes from an impoverished Mexico and Central America would eventually lead to a politically useful new demography or that the United States should use its resources to help the foreign poor by inviting them to enter America.”

“How odd that America’s current progressive turn to tribalism and primary self-identification by race and gender is reactionary to the core…identity politics is at its essence precivilizational…Once tribalism takes hold, it is almost impossible to thwart this ancient narcotic or to prevent it from destroying the centuries-long and much harder work of establishing multiracial nationhood and citizenship.”

“…the charge that…'”systemic racism,” permeates all of American society is rarely demonstrated. Still, the charge is put to good use by the industry of diversity that must find ever-subtler ways of tracking down biases by employing terms like “microaggressions” and “implicit bias” that reveal by their very qualifiers a poverty of such overt pathologies.”

The ‘deep state’ emerged howling from the swamp when Donald Trump was elected President. A cabal of forces – the bureaucracy, the arms of government, corporate America, including Big Tech, State houses, and, critically, the Fourth Estate – allied in an effort to sweep him away, in Wotan fashion. It worked. But what of the cost? As the author observes: “…when journalistic bias is institutionalized and serves the state with the speed and electronic massaging of the internet, the citizen becomes orphaned from the world around him.”

Of the absurd aspects of globalisation, Hanson is particularly on song: preening Davos hypocrites; virtue-signalling, treacherous billionaires and academic groves both extolling the humanity of their commercial overlords, the Chinese Communist Party; jet-setting warmists; the deeply woke deep state; traitorous ‘citizens of the world’ who deprecate border walls whilst building them around their residences, for whom a national constitution is but a guideline. Referring to governance in California, where he lives, Hanson notes the global symposia held there where handwringing over foreign poverty and destitution occurs, while that great state degenerates into a basket case, where the fabulously rich and the most wretched untermensch live almost side by side, akin to the stark divide one sees in places such as Rio. His take:

“In sum, globalization rests on few poorly examined laws…Discussions of abstract cosmic challenges – achieving world peace, cooling the planet, lowering the seas, dismantling secure borders – are psychological ways to square the circle of failure to solve concrete problems at home from war to poverty.”

Hanson ends the book with a comment on the rise of a nationalist (Donald Trump) and how his somewhat inchoate attempts to revive American citizenry were done down by the very forces now hell-bent on turning the idea of America into an irrelevant and irrational confusion, as seen in that wrought by the puppeteers of the current administration. Under President Biden, the southern U.S. border is a porous catastrophe, with some 2 or more million undocumented and un-vetted illegals entering and at large, along with hefty supplies of Chinese-supplied fentanyl and Covid-19; An emotive and brain-addled foreign policy conducted by officials who seemingly can’t read a map or have never won a war; An education establishment bent on Marxist indoctrination, gender propaganda and racked by anti-Americanism; Soaring inflation higher than any in the last two or three generations, amounting to a new payroll tax; Burgeoning crime left undisturbed by law enforcement and prosecution; Mass confusion over which tribe is in the ascendant at any time and tribal identifiers drawn from wish and affect rather than logic and fact; An Executive that flouts Court Orders and carries little weight with the Legislature, and two people occupying the highest positions and authority in the U.S. who are manifestly unequipped for the role.

One wonders if American citizenship is dead, or just coughing up blood. Truly, there are signs of a re-set. One can but hope.

Convenience Store Woman (Sayaka Murata)

(2018 translation from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori)

Keiko Furukura isn’t a convenience store worker, she is part of a convenience store. “I was wasting time talking like this. I had to get myself back in shape for the sake of the store. I had to restructure my body so it would be able to move more swiftly and precisely to replenish the refrigerated drinks or clean the floor, to more perfectly comply with the store’s demands”. Keiko is content living as a cell in a convenience store, but her family and her (very few) friends are not content. “‘Keiko, aren’t you married yet?’ ‘No, I’m not.’ ‘Really? But…you’re not still stuck in the same job, are you? ‘ I thought for a moment. I knew it was considered weird for someone of my age not not have either a proper job or be married because my sister had explained it to me.” Keiko has to have things explained to her because she truly has no idea how to be ‘normal’. She mimics other people. “I’d noticed soon after starting the job that whenever I got angry at the same things as everyone else, they all seemed happy…Now, too, I felt reassured by the expression on Mrs. Izumi and Sugawara’s faces: Good, I pulled off being a ‘person’. I’d felt similarly reassured any number of times here in the convenience store.’

Keiko has worked part-time at the Hiiromachi Station Smile Mart for eighteen years. Five or more mornings each week, Keiko recites the shop pledge and the six most important phrases for customers. Then she follows her routine; restocking shelves, working the till, shouting greetings and the details of the daily specials at the top of her lungs. (Those daily specials include such delights as the mango chocolate bun and chocolate-melon soda). At night Keiko nourishes and rests herself in her tiny, cockroach-ridden apartment so that she can efficiently serve the store the following day. On her days off she visits her friends, not because she enjoys doing so, but because it’s the only connection she has “to the world outside the convenience store” and it seems to be the normal thing to do. These friends, and particularly their husbands, think that Keiko is very odd indeed, but she doesn’t notice. Her sister is at her wit’s end. “‘Ever since you started working at the convenience store, you’ve gotten weirder and weirder. The way you talk, the way you yell out at home as if you were still in the store, and even your facial expressions are weird. I’m begging you. Please try to be normal!’ She began crying even harder. ‘So, will I be cured if I leave the convenience store? Or am I better staying working there? And should I kick Shiraha out? Or am I better with him here? Look, I’ll do whatever you say. I don’t mind either way, so please just instruct me in specific terms.

There are hints that Keiko, lacking understanding and emotion, could be dangerous. She hits a boy with a shovel and thinks how easy it would be to silence a crying baby with a knife.

In order to be more socially acceptable, Keiko has moved a male former co-worker, the ghastly Shiraha, into her apartment. It’s a beautiful relationship. (Shiraha speaks: “People who are considered normal enjoy putting those who aren’t on trial, you know. But if you kick me out now, they’ll judge you even more harshly, so you have no choice but to keep me around,’ Shiraha gave a thin laugh. ‘I always did want revenge, on women who are allowed to become parasites just because they’re women. I always thought to myself that I’d be a parasite one day. That’d show them. And I’m going to be a parasite on you, Furukura, whatever it takes.’ I didn’t have a clue what he was going on about. ‘Well anyway, what about your feed? I put it on to boil, and it should be done now.’ ‘I’ll eat it here. Bring it to me, please.’ I did as he said and put the boiled vegetables and white rice on a plate and took it into the bathroom. ‘Close the door behind you, will you?'” )

Shiraha’s endless references to the Stone Age don’t bore Keiko particularly. Nor does she understand them. Shiraha again: “‘ That’s why contemporary society is dysfunctional. They might mumble nice things about diversity of lifestyles and whatnot, but in the end nothing has changed since prehistoric times. With the birthrate in decline, society is regressing rapidly to the Stone Age, and it’ s going beyond life just being uncomfortable. Society has reached the stage in which not being of any use to the village means being condemned just for existing.’ Shiraha wasn’t just picking on me; he was openly expressing his fury against society. I wasn’t sure which of us he was angrier with. He seemed to be just throwing out words randomly at whatever happened to be in his sights.”

Due to her new relationship, and to her amazement, Keiko, becomes an object of interest to her co-workers. “I was shocked by their reaction. As a convenience store worker, I couldn’t believe they were putting gossip about store workers before a promotion in which chicken skewers that usually sold at 130 yen were to be put on sale at the special price of 110 yen. What on earth had happened to the pair of them?”

Convenience Store Woman is often called funny, comical. It is, but in the wry manner of Flannery O’Connor, John Kennedy Toole or the Evelyn Waugh of “The Loved One” (although these were greater authors of the grotesque than Murata (yet?) is.) It is also a perceptive study in, to use the woke term, ‘neurodiversity’. At a mere 163 pages, Convenience Store Woman is just the right length, best downed in one gulp, like a chocolate-melon soda. Unlike the soda though, it’s worth trying.

Crossroads (Jonathan Franzen)

The first volume of Jonathan Franzen’s saga of contemporary American family life, “Crossroads” (2021) promises less to come.

The Hildebrandts of New Prospect are falling apart and they don’t know it. Worse still, they are unremittingly dull, and the author doesn’t know it. The hypocritical, craven pastor father, Russ, lusts after a parishioner. He despises his peculiar and repressed wife, Marion. He loathes a popular youth worker at the church ‘Crossroads’ group. He acts inappropriately with teenaged girls. That’s about all he does. The Hildebrandt parents barely register their children – the all-American elder son, the thinly-realised daughter, the drug-addled middle son and the barely-there youngest child (who is clearly being saved for the sequels). However, after a crisis Russ and Marion are shocked into noticing and indeed, doting on one of their turgid offspring at the expense of the others.

The Hildebrandts and their circle are all generally unobservant, unpleasant people which wouldn’t matter if they were of interest, but they are not. Russ and Marion’s pasts are probably the best parts of the novel, but by the time of the current action, they have become dreary people raising dreary children. Franzen spells out every character’s every thought. Characters talk things through in just the way real people don’t. “‘I don’t know how it happened,’ Russ said. ‘How I came to hate you so much. It goes way beyond pride – it’s basically consumed my life, and I don’t understand it. How can I be a servant of God and feel this way. Just being in this office is a torture. The only thing I can say in my defence is that I can’t control it. I can’t think of you for five seconds without feeling sick. I can’t even look at you now – your face makes me sick.’ He sounded like a little girl running to her parent with hurt feelings. Mean Rick made me feel bad. ‘If it’s any comfort,’ Ambrose said, ‘I don’t like you, either. I used to have a lot of respect for you, but that’s long gone.”” Marion even gets her own therapist to explain herself to in expository dialogue.

There is a long late section about a church working camp supposed to benefit Navajo communities. It feels manufactured and allows Franzen to patronise the reader with his views of ‘spirituality’ and ‘social justice’. Just what this book needs; a sermon.

There are some nice scenes – a frightening car ride in Italy; the teenaged drunken Perry disgracing himself at a clergy party:-

“Reverend Haefle placed a gentle hand on Perry’s shoulder. More roughly than necessary, Perry shook it off. He knew he needed to calm down, but the heat in his head was extraordinary. ‘This is what I’m talking about,’ he said very loudly. ‘No matter what I do, it’s always me who’s in the wrong. You’re all saved, but apparently I’m damned. Do you think I enjoy being damned?’ A sob of self-pity escaped him. I’m doing the best I can!’ The living room was now completely quiet. Through tears, he saw twenty pairs of clerical and spousal eyes on him, among them, near the front door, to his shame and dismay, were his mother’s.”

Franzen has taken on big issues. The dangers of sliding past family members until you collide, wasted years, blinkered self-absorption, responsibility to the community, individuality, how to be good, God, Jesus, sex, drugs, long hair, sex, Jesus and drugs. But the book has no depth. Franzen’s efforts to evoke the numinous and ineffable are given in trite discussions between clergy or Perry’s drugged ravings.

Perry Hildebrandt, by the way, is alleged to have an IQ of 160. We see no evidence of his supposed genius other than his rants when high. Which read like a paraphrasing of a Wikipedia entry. “‘…She’s a total F-O-X. And I don’t mean some esoteric oxyfluoride salt of xenon, although, interestingly, they’ve synthesized some salts like that, in spite of the supposed completeness of xenon’s outermost electron shell, which you’d think couldn’t happen, and, yes, I realize I digress. My point in mentioning chemistry was that it’s not the point, but you must admit it’s pretty incredible. Everyone assumed that xeon was inert, I mean it’s such a credit to the fluorine atom – its oxidizing powers. Wouldn’t you agree that it’s incredible.”

The book takes no risks with character or plot. That is not to say that either should be unrealistic – this is, after all, a study of mundanity (with aborted sojourns in the foothills of philosophy) but we feel that Franzen is husbanding the people and the twists of fate for the later books in the trilogy. For example, a character who should be dead is spared. The reader is not.

Nitram

(Directed by Justin Kurzel) (2021)

Suspense need not be a mystery. Out of the so-called 7 plots, the dramatist’s art is to finesse the selected one. As with Shakespeare, it matters not that we know the ending. In Nitram (‘Martin’ backwards, as is Martin), the story (about Martin Bryant, going ‘postal’ in April 1996) is notorious. Here, the director creates an intimate, very private background to a very public tragedy, and does it with great depth of feeling and beautiful pacing.

It is a small town saga (the south-east coast of Victoria standing in for Port Arthur, probably for political reasons, or perhaps basic human sensitivity), as we meet Martin (never, by our reckoning, named throughout), an overaged child, obviously challenged and with arrested development, apt to do dangerous things, and his desperately miserable parents. The futile efforts to treat his mental problems are disturbing and overfamiliar, evoking a desire for the building of a new, kinder Bedlam. Inevitably, the issue of access to guns arises – a worthy debate, discussed in our account of the real event (linked above) but here it is not sledgehammered home (and probably does not need to be).

After want and emotion conquer logic and fact, Martin moves out, and then in with the crazy cat lady, for whom he has failed to mow the lawns. She turns out to be a rich eccentric (natch) who stakes Martin in his absurd ambitions – till it all goes wrong.

Lottery of Life

There can be no quarrel with the acting. Judy Davis, as harsh-but-fair Mum, and Anthony LaPaglia, as weak, defeated and ineffectual Dad, are superb. Essie Davis is wonderfully blurry as Helen of the dogs and cats. The supporting cast are all good, particularly the not-so-nice surfie (Sean Keenan) who decides, in good time, to stop razzing Nitram. The film belongs to Caleb Landry Jones, however, as the man-child. He has specialised in portrayals of damage (Get Out, Three Billboards…) and here he is vibrant with anger and confusion, and with an authentic Australian accent to boot.

The conclusion may be discreet, even tasteful, but the build-up has been so vivid by then as to leave the viewer vaguely cheated of a violent catharsis. Ignoring the massacre is a plausible move from an interesting director prone to strategic mistakes – vide his Macbeth. Elephant managed to show a rampage without being exploitative: surely here a way could have been found (perhaps showing Nitram on his lethal errand without displaying the bodies piling up). Along the way, there are touches here and there that whilst satisfying dramatically are freighted with the baggage of elucidation: for examples, Nitram recalls burning himself with his beloved firecrackers – and resolves to keep on lighting them; Mum tells Helen about the time sonny went missing and laughed at her fear and pain. These would apply to a thousand healthy boys: there really need and perhaps should be no attempt in an entertainment such as this to even try to explain.

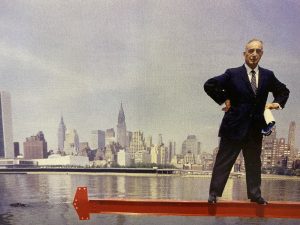

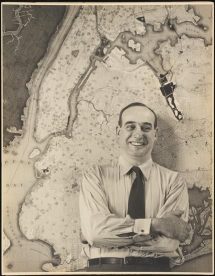

Continue Reading →The Power Broker

(Robert Moses and the Fall of New York) (by Robert A. Caro, 1974)

That this brick of a book (well over a thousand pages) about public infrastructure is so compelling is due to, first, its traverse of key decades in the rise of America (1920s to the 1960s); second, the author’s awesome depth of research and keen grasp of his subject; and third, the subject himself: the most famous public official in New York (perhaps America), Robert Moses (18 December 1888 – 29 July 1981), a humanities man, without engineering qualifications, who yet singlehandedly matched the Pharaohs and the Romans in empire building. Under Moses’ forty odd years in power, his list of NYC credits is staggering (this link is not exhaustive: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Robert_Moses_projects) and includes over 650 playgrounds, over 100 state parks, over 400 miles of parkways, countless urban expressways, bridges linking the NYC boroughs, tunnels linking them under the waters, man-made beaches, boat basins and aquatic infrastructure, low rent housing apartments, causeways and dams, the United Nations complex, the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Shea Stadium, the NYC Coliseum, the Astoria Pool, the 1964 World’s Fair, and a myriad other bits and bobs. He “built public works costing, in 1968 dollars, twenty-seven billion dollars.”

Obviously Moses was the greatest planner (and, crucially, implementer) of public works in the history of the United States, perhaps of the whole modern world. Caro tracks and acknowledges the tremendous achievement, but he also does what few did during the reign of Moses – count the cost. Moses conceded that:

“You can draw any kind of picture you like on a clean slate and indulge your every whim in the wilderness in laying out a New Delhi, Canberra or Brasília, but when you operate in an overbuilt metropolis, you have to hack your way with a meat ax.”

Moses destroyed as fervently as he created. And he did whatever it took, engaging in corrupt behaviour so noxious that he would have faced charges but for the key fact that he never lined his own pockets. Indeed, power was his drug, not love, fame, nor money. As Lord Acton said, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men.” Robert Moses is a classic example, a perfect specimen, at whose door many floral tributes lie, and for whom the operative word is “lie.” He brooked no arguments; he never changed his plans.

Caro follows Moses from his fairly comfortable youth and student days at Yale and Oxford. While an idealist, he displayed early signs of sharp practice. And after his attempts at public service reform (pursued by him with enthusiasm, naivety and arrogance) left him bruised and blackballed by the New York Tammany machine, he became “scornful…of what he had been.” Forming a deep alliance with NY Governor Al Smith in the 1920s, Moses became not only adept but supreme in the dark arts of governance (persuasion, intimidation, dissembling) – and got his first taste of power. He learned by watching Smith “twist arms, offer incentives and drop, one by one, with matchless guile, the veils from in front of threats.” But Smith had a strong social conscience and tried hard to help the helpless. Moses was less idealistic: he preferred to use power to realise his dreams.

He started on Long Island. Put in charge of State Parks, he wheeled-and-dealt with breathtaking deviousness, flair and diligence. Appropriating, haggling, exploiting the good will, slow wit and altruism of others, he grabbed or re-claimed land and created some 20 major state parks on the island (not Arcadian glades that some of his old-money patrons desired, but ‘working parks’ which were often “banal“) – with major expressways or parkways to access them from the boroughs to the west. For a man that never learned in 93 years to drive, he enabled New York over time to be engulfed by the automobile: creating great new expressways through his autonomous vehicle – the commissions and authorities gathered under the heading ‘Triborough Authority,’ which became (through private bonds and public tolls) richer and more powerful than the City of New York itself. He used that power to blackmail (and at times avenge) the so-called powers-that-were. Sheer talent and hard work were not enough: at some point, this remarkable man, who had long studied and tried to repair local government, concluded that the only way was to skirt, ignore, and supplant it. With Smith’s complicity, he tweaked legislation and executive action to ensure that he kept total control of planning, finance, acquisition, construction, and remuneration. He made a quango not dependent on public finance. He became a one-stop shop, if you wanted any development done in NYC.

Along the course of such development, he rode roughshod over the rights of landholders. He evicted (sometimes prematurely and capriciously) a quarter of a million poor people (many African-Americans and Hispanics, not his preferred people) from rent-controlled apartments and left them to find other accommodation. He ignored the law, often ordering his construction crews to demolish before an injunction was granted, sometimes even afterwards. He would misrepresent the costs of a project, knowing that by the time it was underway, elected officials were compromised and powerless not to appropriate further funds. “Misleading and underestimating, in fact, might be the only way to get a project started.” He hid inconvenient facts, demonized opponents or even those with legitimate questions, and viciously used and abused the power of the press, especially of his friends at the New York Times and The Daily News. Having made one disastrous run at the Governorship in 1934, he instead skirted, ignored and supplanted democracy. But he also out-thought and out-prepared adversaries and generally bested them in argument (and invective). It is significant that, with no driver’s licence himself, he turned his limousine into a mobile office, working and planning and plotting as he was chauffeured all over the City and State of New York: he was simply more driven than anyone else.

NYC Mayors, from the formidable Fiorello La Guardia to the dilettante John Lindsay, tried to control or eject him: they failed. Governors, from Franklin D. Roosevelt to W. Averell Harriman, tried to do so: they failed. (FDR even tried when he became President in 1933 – he failed, asking an aid, “Isn’t the President of the United States entitled to one personal grudge?” to be told “No“). Moses would threaten to resign, knowing he was indispensable, which for quite some time, was true. He would threaten to go to the press. He would call in all his rent & fee seeking pals and partners in the unions, banks, construction companies, et al to write memos, make calls and spread smears. He would bully anyone. Once Triborough was established, it was financially independent and all-powerful, and virtually untouchable until bad decisions and decay started to afflict Moses’ built legacy, lost fights tarnished his reputation and hold on a new generation of the pressmen, age weakened his grip, and a Governor whose wealth and ambition put him above everything, prevailed: Nelson Rockefeller.

The Power Broker is a superb study of politics and power, and a biography that brilliantly proves Solzhenitsyn’s dictum, in The Gulag Archipelago, that “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”