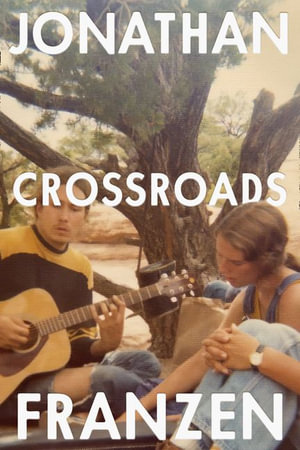

Crossroads (Jonathan Franzen)

The first volume of Jonathan Franzen’s saga of contemporary American family life, “Crossroads” (2021) promises less to come.

The Hildebrandts of New Prospect are falling apart and they don’t know it. Worse still, they are unremittingly dull, and the author doesn’t know it. The hypocritical, craven pastor father, Russ, lusts after a parishioner. He despises his peculiar and repressed wife, Marion. He loathes a popular youth worker at the church ‘Crossroads’ group. He acts inappropriately with teenaged girls. That’s about all he does. The Hildebrandt parents barely register their children – the all-American elder son, the thinly-realised daughter, the drug-addled middle son and the barely-there youngest child (who is clearly being saved for the sequels). However, after a crisis Russ and Marion are shocked into noticing and indeed, doting on one of their turgid offspring at the expense of the others.

The Hildebrandts and their circle are all generally unobservant, unpleasant people which wouldn’t matter if they were of interest, but they are not. Russ and Marion’s pasts are probably the best parts of the novel, but by the time of the current action, they have become dreary people raising dreary children. Franzen spells out every character’s every thought. Characters talk things through in just the way real people don’t. “‘I don’t know how it happened,’ Russ said. ‘How I came to hate you so much. It goes way beyond pride – it’s basically consumed my life, and I don’t understand it. How can I be a servant of God and feel this way. Just being in this office is a torture. The only thing I can say in my defence is that I can’t control it. I can’t think of you for five seconds without feeling sick. I can’t even look at you now – your face makes me sick.’ He sounded like a little girl running to her parent with hurt feelings. Mean Rick made me feel bad. ‘If it’s any comfort,’ Ambrose said, ‘I don’t like you, either. I used to have a lot of respect for you, but that’s long gone.”” Marion even gets her own therapist to explain herself to in expository dialogue.

There is a long late section about a church working camp supposed to benefit Navajo communities. It feels manufactured and allows Franzen to patronise the reader with his views of ‘spirituality’ and ‘social justice’. Just what this book needs; a sermon.

There are some nice scenes – a frightening car ride in Italy; the teenaged drunken Perry disgracing himself at a clergy party:-

“Reverend Haefle placed a gentle hand on Perry’s shoulder. More roughly than necessary, Perry shook it off. He knew he needed to calm down, but the heat in his head was extraordinary. ‘This is what I’m talking about,’ he said very loudly. ‘No matter what I do, it’s always me who’s in the wrong. You’re all saved, but apparently I’m damned. Do you think I enjoy being damned?’ A sob of self-pity escaped him. I’m doing the best I can!’ The living room was now completely quiet. Through tears, he saw twenty pairs of clerical and spousal eyes on him, among them, near the front door, to his shame and dismay, were his mother’s.”

Franzen has taken on big issues. The dangers of sliding past family members until you collide, wasted years, blinkered self-absorption, responsibility to the community, individuality, how to be good, God, Jesus, sex, drugs, long hair, sex, Jesus and drugs. But the book has no depth. Franzen’s efforts to evoke the numinous and ineffable are given in trite discussions between clergy or Perry’s drugged ravings.

Perry Hildebrandt, by the way, is alleged to have an IQ of 160. We see no evidence of his supposed genius other than his rants when high. Which read like a paraphrasing of a Wikipedia entry. “‘…She’s a total F-O-X. And I don’t mean some esoteric oxyfluoride salt of xenon, although, interestingly, they’ve synthesized some salts like that, in spite of the supposed completeness of xenon’s outermost electron shell, which you’d think couldn’t happen, and, yes, I realize I digress. My point in mentioning chemistry was that it’s not the point, but you must admit it’s pretty incredible. Everyone assumed that xeon was inert, I mean it’s such a credit to the fluorine atom – its oxidizing powers. Wouldn’t you agree that it’s incredible.”

The book takes no risks with character or plot. That is not to say that either should be unrealistic – this is, after all, a study of mundanity (with aborted sojourns in the foothills of philosophy) but we feel that Franzen is husbanding the people and the twists of fate for the later books in the trilogy. For example, a character who should be dead is spared. The reader is not.

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

0 Comments