The Varnished Culture's Thumbnail Reviews

Regularly added bite-sized reviews about Literature, Art, Music & Film.

Voltaire said the secret of being boring is to say everything.

We do not wish to say everything or see everything; life, though long is too short for that.

We hope you take these little syntheses in the spirit of shared enthusiasm.

A Distant Episode

(by Paul Bowles)

Like the cove in George Orwell’s piece about bookshops, we generally ‘do not desire little stories’, yet this is P’s personal favourite, along with Joyce Carol Oates’ Where are You Going, Where have You Been?. Warning: Both stories are particularly nasty.

Continue Reading →The Dinner Game

(dir. Francis Veber) (1998)

Kenneth Tynan said that you have to be cruel to be kind in high French comedy. In the present case, a bunch of nasty Parisian swells convene a regular dinner in which they have to bring along an unsuspecting dill, each with his own dumb hobby/obsession that their hosts can suavely, and discretely, mock. The book publisher’s friend has, by accident, found an idiot for the next round – in fact, he’s a world champion. But most satisfyingly, cruelty loses to stupidity in this sublime Gallic turn, and one also learns how many matches it takes to build the Eiffel Tower.

Continue Reading →A Delicate Balance

(dir. Tony Richardson) (1973)

One Friday night a tense little New England family receives a surprise visit from a couple of old friends. It seems they were at home and suddenly ‘became frightened’ for no apparent reason. So they decide to move in with their oldest friends, opening up some old, and some still warmly moist, scars, testing the limits and concept of true friendship.

More delectable, drunken, hate-filled east coast dummy-spits from Edward Albee. The Varnished Culture always draws the cat’s attention to what might happen to him if he ever “doesn’t like us anymore”.

Continue Reading →Defend the Realm

(by Christopher Andrew) (Other editions entitled The Defence of the Realm)

The author is suited to the task of telling MI5’s story and not just because he’s a Cambridge man. Impeccably credentialed and given an exclusive entreé to classified material, Mr Andrew provides a rational, impartial and exquisitely detailed work, easy to read and to read compulsively.

Continue Reading →

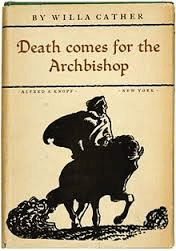

Death Comes for the Archbishop

(by Willa Cather)

A series of disappointingly empty episodes in old New Mexico, where the priests are as mixed a bag as anywhere else.

Continue Reading →Dead Souls

(by Nikolai Gogol)

Gogol was no Dante. He could not legislate in his novels. But he pinned sinners more lethally than most and the wild scheme to buy and sell the dead, today, looks a lot like dealing in derivatives.

The dead souls were peasants who had passed on between official census, and hence you incurred their holding costs (tax) till they were officially designated as dead at the next census. The protagonist, Chichikov, would acquire those dead souls, thereby assuming the tax burden of them, but he would mortgage them as live souls till the next census.

Priestley wrote “On the gothic tower of romanticism, Gogol is responsible for the gargoyles.”

Continue Reading →Dead Man

(dir. Jim Jarmusch) (1996)

Johnny Depp rides again, or should it be sails, into the sunset, only this time, weird works.

[As Depp Indian films go, this is as good as The Lone Ranger is execrable…] Continue Reading →