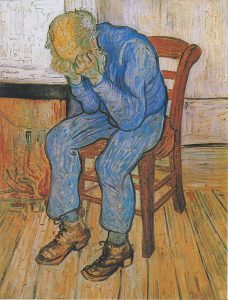

At Eternity’s Gate

(Directed by Julian Schnabel) (2018)

It takes some men a long time to grow up. Julian Schnabel began his career as an artist, allegedly; his notorious ‘plate paintings’ moved Robert Hughes to say of him: “Schnabel’s work is to painting what Stallone’s is to acting: a lurching display of oily pectorals.”* Then he produced a memoir, when only aged in his mid-thirties, without having achieved anything of note – if you want a nasty laugh, read Hughes’ review of it in The New Republic.** Then he found the medium of film, where his talents and sensibilities obviously lie: after Basquiat (1996) a poor biopic of the completely talent-less American pop-artist, he showed promise with The Diving Bell and the Butterfly (2007). Now he turns his attention to a true Giant, Vincent van Gogh, in a new bio-pic that strays from the path of fact but manages to find new truths.

In short, happily (perhaps miraculously), Schnabel’s film is magnificent, a truly moving, revelatory work of art that manages to persuade us of, though not necessarily prove, Vincent’s compulsion to ‘rest the imagination’ through his pictures, to “express what he felt, and if distortion helped him to achieve this aim he would use distortion.”^ Much of the film is dialogue-free, and we get numerous scenes of the artist out bush, communing with and imbibing nature, straining to paint what he sees. The script, incidentally, is not often more than adequate, but what works so well is the “vibe” – the pulse of Gogh’s genius and madness that drive him to do ugly things, paint some very ugly pictures, and produce at least a dozen masterpieces, the stuff that will one day make and break the fortunes of others.

Schnabel uses a restless, almost too inquisitive camera, resting on characters’ chins and stalking them through the shrubbery. P liked, although L didn’t, the director’s conceit of a partially smudged camera, especially when we viewed the world through the artist’s eyes, a comment perhaps on defective vision, frustrated comprehension or simply post-impressionism. Like the dissonant musical score, a splash of piano keys and the odd violin beaten black and blue, the home-craft nature of the production sorts beautifully with the rural squalor on show.

Time to do what actors most like: talk about them. Willem Dafoe is magnificent as Vincent. Though much older than the artist in his last years (Kirk Douglas looked much more like him in Lust For Life) Dafoe channels him perfectly, capturing all of his fears, inhibitions, his social ineptitude, crazes, anger, sense of doom, gentleness and fervour. We see an almost comprehensive sketch – a minor miracle in film biography, as he moons about the countryside; crouches defensively in the asylum or the rectory; and talks with his gentle and protective brother Theo (Rupert Friend) or his painter colleague Paul Gauguin (Oscar Issac, below, in a quiet but sharp performance, rendering the brilliant synthesist in a much kinder portrait than we find in, say, The Moon and Sixpence). Defoe’s playing is so good that we confidently expect him not to win an Oscar, even as a late career present*^.

A number of actors appear, amusingly, as the models for some of Vincent’s greatest hits (see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_works_by_Vincent_van_Gogh): Dr Gachet, Madame Ginoux, the mad soldier in Saint-Paul Hospital, the postie Joseph Roulin. Vincent’s paintings are his biography, so much of the visual script, mainly locations in Paris and Arles, has been done already. But Schnabel’s taste and discretion make a hitherto rare break from cover in this film: we are generally spared touristy flourishes – no bedroom at Arles, thank god. What we do see is the driven genius, happily free from cliche. For example, when Vincent returns to a grim, mistral-frozen, window-rattling, spartan room, he doesn’t make a fire and take a little wine: he takes off his boots and starts, and finishes, a picture of them. By the way, the painterly and sketching activities are beautifully done.

There are some odd jarring notes. When Mads Mikkelson (below), as a priest supervising the artist’s treatment, suggests gently (but persistently) that perhaps Vincent has missed his calling, he draws a riposte from Gogh that he will be appreciated by later generations. This struck us as as a flourish: false, and dumb…not Vincent at all. Dare we suggest that the script was channeling ‘the Plate Man’ at that point?

And the conclusion was somewhat odd. There is no evidence that we know of to suggest that Vincent was shot dead by two boys playing Cowboys and Indians. And we did not quite know what to make of the last scene: a closing-down sale of Vincent’s paintings, with the artist lying in his coffin amid them. This a shot at the rapacious modern art world, we guess, but it sat ill. The better end came after the credits: an epitaph spoken by Gauguin, the screen painted a luminous yellow, Vincent’s favourite colour.

[*Time, 7/8/2012.] [**1987: Hughes’ review is reproduced in his collection Nothing if Not Critical (1990).] [^ E.H. Gombrich, The Story of Art (1950), p. 423.] [*^ As we predicted, Dafoe did not win. As Vincent might have said: “Zo is het leven” (that’s life).]

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

0 Comments