Divina Commedia

See for yourself, or read the Book (painting by Domenico di Michelino, 1465)

(by Dante Alighieri 1/6/1265 – 14/9/1321) (completed 1320)

[Note: extracts are from, and reference is to, the John Ciardi translation]The greatest epic poem of all time (and we can say this with confidence, despite the dodgy standard of TVC’s latin).

It has a brilliantly (classically) simple structure – Recounting, in terza rima, how Dante spends the 1300 Easter vacation on a salvational tour of the worlds of our minds (and souls), guided through Hell and Purgatory by his poetic mentor, Virgil and accompanied by his poster-girl, Beatrice, in Paradise. There they meet Dante’s fiamma benedetta a flame of heavenly wisdom, S. Thomas Aquinas. S. Thomas was a formidable thinker but no great writer. Dante, taking hold of the 13th C theologian, supplied the art. “it is the flame, eternally elated, of Siger, who along the Street of Straws syllogized truths for which he would be hated.” (Pa. X) But he did something more: he created a new universe. And it was a universe that left Aquinas and Augustine, the best of the ancient Christians, pounding in the wake of something strange and monolithically modern. As Harold Bloom said with his usual wisdom in The Western Canon, “The Comedy…destroys the distinction between sacred and secular writing.”

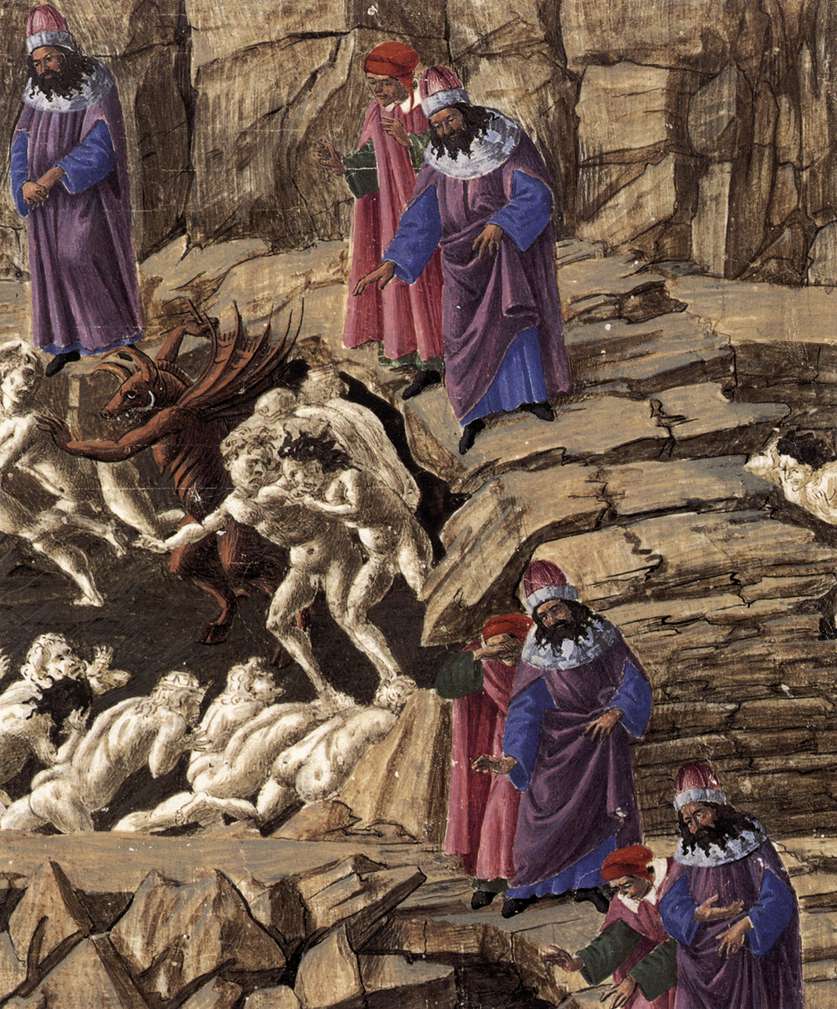

One of Sandro Botticelli’s drawings for Divina Commedia

The Comedy is the product of a literary magpie. Dante’s beak dips into scripture, classical pagan writing, European politics, local and familial affairs. The result of this accumulative density is a tower to house a Dante industry, a tower the height and volume beside which James Joyce Inc. pales into a noon shadow.*

There is a very medieval pattern of symmetrical numbers: we follow the nine circles of Hell, and then say “Hi” to Satan; ascend the nine rings of Mount Purgatory, then, washed clean of sin and ignorance, loiter in Eden and float about the nine celestial spheres before entering the Empyrean and regarding the mystic rose, the kind of trope Guillaume de Lorris wrote about, circa 1237. Ultimately, Dante rests after his work’s outing, musing on Paradise that “…already I could feel my being turned – instinct and intellect balanced equally as in a wheel whose motion nothing jars- by the Love that moves the Sun and the other stars.”

Dante used this gigantic, preternatural road trip to see scores settled, of course: indeed, it constitutes something of a revenger’s fable on the Ghibellines and Pope Boniface VIII, conceived on a titanic scale.

It is the perfection of brevity with which Dante encapsulates difficult and large matters. Take, for example, his (as it were) temporal depiction of the timeless:

“Nor did He lie asleep before the Word sounded above these waters: ‘before’ and ‘after’ did not exist until His voice was heard.” (Pa. XXIX)

Or this precursor to C.S. Lewis; “The double grief of a lost bliss is to recall its happy hour in pain.” (Inf. V)

“nor can we admit the possibility of repenting a thing at the same time it is willed, for the two acts are contradictory.'” (Inf. XXVII)

Or this paradisiacal arbitrariness: “…the Supreme light fittingly makes fair its aureole by granting them their graces according to the color of their hair. Thus through no merit of their works and days they are assigned their varying degrees by variance only in original grace.” (Pa. XXXII)

Dante was only aged 9 when he first saw Beatrice, “the woman whom my mind beholds in glory…” In Purgatory, Beatrice does not so much replace Virgil as allow Dante to supplant Virgil. Whereas the great and the almost good revere Virgil (e.g. Sordello kneels before him: Pg. VII), he is the past. B is a super Muse, telling Dante to ‘man up’, ‘dry your eyes, Bono’ and ‘suck it up’. “‘Dante’” she says, naming the great man for the first and only time, “‘do not weep yet, though Virgil goes….Did you not know that here man lives in bliss?’”

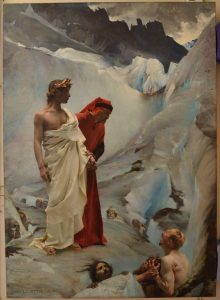

“Hey, good lookin'” (painting by Henry Holiday)

It is chilling to consider literary fashion. There really ought to be no such concept. Yet, as J. B. Priestley reminds us in Literature and Western Man (1960), “…the enlightened age of Voltaire looked down on Homer and Dante and regarded Shakespeare as a clown and a barbarian…”

But Dante Alighieri is secure. His proud shadow falls even on poets who never heard of him.

The influence of Dante’s work is, obviously, immense, too gargantuan and complex to cover here. Just a few examples will serve TVC’s purposes:

Ezra Pound, in Canto XXXVIII, cites Paradiso XIX, concerning debasement of currency. Dante dressed this sin (his charge against Philip of France) as one of a salad; Pound, alas, tended to focus, to an unwholesome degree, on usury and currency speculation.

T.S. Eliot, in The Waste Land, footnotes Inferno III and IV, but his whole poem is drenched in Dante. In his little book on Dante, he observes: “The majority of poems one outgrows and outlives, as one outgrows and outlives the majority of human passions: Dante’s is one of those which one can only just hope to grow up to at the end of life.”

In just about every celestial painting by William Blake, and others, one sees the cantos of Dante.

Osip Mandelstam, during his exile in the Urals, wrote Conversation About Dante. He identified the way Dante loosed his demotic Tuscan on the world and helped clear the way forward. He said this: “The creation of Dante is above all the emergence into the world arena of the Italian language of his day, its emergence as a whole, as a system.” George Steiner, in his difficult but rich book, After Babel, highlights “Mandelstam’s penetrating comment on Dante and on linguistic form [which] echoes his own asphyxia under political terror, in the absence of tomorrow.” Steiner goes on to consider Rudolf Borchardt, who concluded that “Dante’s absence from the history of the German language and of German sensibility in the period 1300-1500 destroyed deep logical and material affinities between German feudalism and the ‘classical’ Christendom of the Provence and of Tuscany.”

Marx and Engels recognized Dante’s power, and hoped to harness it to their political purposes, acknowledging him as the canon of the middle ages. In the preface to the Italian edition of the Communist Manifesto, Engels wrote: “The first capitalist nation was Italy. The close of the feudal Middle Ages, and the opening of the modern capitalist era are marked by a colossal figure: an Italian, Dante, both the last poet of the Middle Ages and the first poet of modern times. Today, as in 1300, a new historical era is approaching. Will Italy give us the new Dante, who will mark the hour of birth of this new, proletarian era?” [No.]

H. W. Longfellow was the first American translator of The Divine Comedy. In his poem, Divina Commedia, he sang: “And the great Rose upon its leaves displays Christ’s Triumph, and the angelic roundelays With splendour upon splendour multiplied: And Beatrice again at Dante’s side No more rebukes, but smiles her words of praise.”

He mesmerized his own generation as well. Vasari notes that Michelangelo “much delighted in readings of the poets in the vulgar tongue, and particularly of Dante, whom he much admired…”

Giotto first met Dante in 1305 and whilst most of his figures in profile look disturbingly like Marlon Brando, this would seem to render the poet aged about 40.

*DANTE’S PEAK: To climb the mountain of works on the Divina Commedia, one might usefully start with two books and their selected bibliographies: The Cambridge Companion to Dante (1993) edited by Rachel Jacoff and Dante and His World (1966) by Thomas Caldecot Chubb. Also see Giovanni Boccaccio, Life of Dante (1374).

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

4 Comments