In Search of Wagner

The sentimental Marat

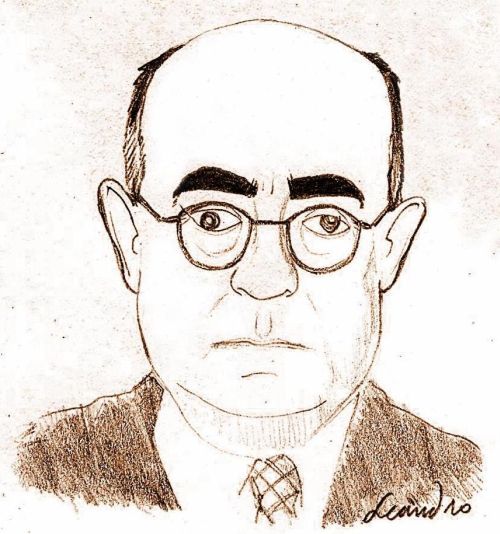

(By Theodor Adorno) (written 1937-38) (Rodney Livingstone translation) (2005)

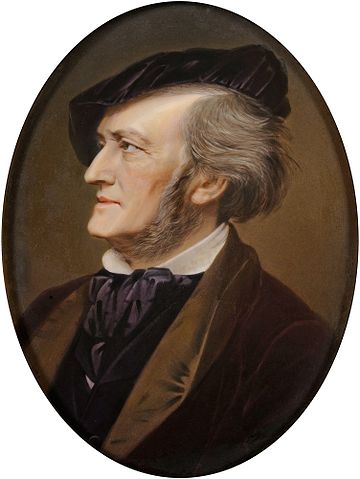

Whilst Adorno (1903 – 1969) was a thinker of wide learning and deep perception, here he is defeated by Wagner, as well as by his own Frankfurter-Marxist dogma and drab obsession with the dialectical. He’d love to dismiss RW as repulsive, dangerous, tin-eared, a Jew-baiter and Jew-hater, formless and, worst of all, bourgeois; yet a kind of intellectual honesty keeps creeping-back in to Adorno’s highly profound skull that undermines all of his grumbling. Wagner is not only sui generis; he is unimpeachable; Adorno’s brilliant attacks, often highly personal, fail utterly, proving our point beautifully. (Wagner would have laughed till he wet his silk underpants).

This book is ponderous, over-freighted with theory, and whilst short, is written in a dense fashion that often collapses under the weight of too many concepts advanced at one and the same time, and bent-out-of-shape by Adorno’s desire to crush the Maestro. Yet all he does is demonstrate how, beneath the barnacles of his apparent musical formlessness, artistic revanchism, anti-semitism and other personal odious qualities, Wagner remains one of the four greatest musical geniuses of history*. Michael Tanner in Wagner rightly says: “Theodor Adorno’s In Search of Wagner is important because of its author, showing how a thinker of genius can be led by reacting to Wagner’s art into wild postures of rejection, and sneaking admiration.” (p.225)

My German is far too weak to read Adorno in the original and comment on the translation by Rodney Livingstone (‘das ist schade’) but I suspect that Adorno is the one to blame for swampy paragraphs such as this:

“The melodic endings within the unending melody are all too apparent. They are only just negotiated by stereotyped interrupted cadences, such as the ‘resolution’ of the dominant seventh onto the second inversion of the dominant seventh of the dominant.” (Forget the technical nature of the opinion, just consider the horrendous syntax, so horrendous as to be truly German.)

However, Adorno has a hell of a lot of fascinating things to say, and whilst he largely stirs a storm in a Nymphenburg tea-cup, he identifies several things about Wagner that, in the final analysis, don’t matter, but cannot be ignored:

Item One: His persona

He is accused (and surely, rightly convicted) of sentimentality, particularly in the cadging for sympathy. Yet off-putting and, indeed, sinister as that quality is, you excuse it in Wagner, who set himself one of the greatest tasks in the history of Art, a re-making of old forms anew. For that, he gets a special pass in TVC’s opinion. Be that as it may, Adorno does pin the butterfly adroitly, especially in his account of Wagner’s perverse sense of humour that appalled his friends, Liszt and Nietzsche among them. Adorno properly cites the weird, cruel and stupid cat-and-mouse game with Hermann Levi, when “every soothing word is accompanied by a new sting…[showing a] sadistic desire to humiliate, sentimental conciliatoriness and above all the wish to bind the maltreated Levi to him emotionally…”

The anti-semitic and rascist streak will always loom large in Wagner, of course. It’s the worst thing about him. Adorno finds his proofs of an all-encompassing pathology in the form of Alberich and Mime from The Ring, and Beckmesser from Meistersinger. (In addition to the fruitful harvest from his many tasteless essays.) To us, Wagner’s prejudice smacks of theory rather than practical malignity, akin to the chap who says “All lawyers are lying, robbing swine; My lawyer, however, is terrific.” In other words, we find his Jew-hate detestable but not subversive of his works, and in practical terms, not necessarily evil or universal. (Adorno might like to read some of his pal, Karl Marx, for perspective on this.)

Item Two: Formlessness

“[In Wagner] all true polyphony is frustrated…Wagner’s melody is in fact unable to make good its promise of infinity since, instead of unfolding in a genuinely free and unconstrained manner, it has recourse to small-scale models and by stringing those together provides a substitute for true development.” (Arguably correct, yet polyphony in many operas is just showing-off, and Wagner had a higher purpose.)

Item Three: Lack of harmony

“…there is an absence of tension in Wagner’s harmony as it descends from the leading note and sinks from the dominant into the tonic. It is the fawning stance of the mother’s boy who talks himself and others into believing that his kind parents can deny him nothing, for the very purpose of making sure they don’t.”

Well, for one I’d suggest that Ted has another listen to the Liebestod, the Siegfried Idyll, Act II of Götterdämmerung, the Fire Music, Trauermarsch, the overtures to Tannhaüser, Lohengrin and Meistersinger, the Good Friday music, even the Ride of the Valkyries, and then shut the heck up!

Item Four: The Dilettante

This is a serious charge, also made by Thomas Mann, who had a bit of time for Wagner (but also for Adorno). We find ourselves voting ‘not guilty,’ purely on the basis that perhaps only Leonardo could reach across such divides as Wagner did in his effort to attain gesamtkunstwerk. The old crack that Wagner was ‘impressionistic’, writing for the ‘unmusical,’ to be heard from a great distance rather than the Viennese chamber, fails to persuade, even though we concede that with Wagner, one often does not surf the wave but watches it from the shore. So what? As for Adorno’s charge that “garrulousness and complacency…mar Wagner’s work at every point,” we say, with the very profoundest respect: “Get your hand off it.”

Item Five: Theatricality

Adorno believes this “repellent aspect of his composition..is grounded in this regression...a museum of long-forgotten gestures…” We would dare to suggest that more theatricality (which in our book means a better sense of a complete presentation of emotion-evoking technique) would have enhanced the operatic work of one whose music attained similar heights…say, Mozart? Wagner’s music-dramas, with influence from Beethoven, Weber and Jew-Boy Mendelssohn, made cinema intellectually (perhaps even to an extent technically) possible, so consider this statement by an early master of that genre, as to theatricality: “I have this terrible sense that a film is dead – that it’s a piece of film in a machine that will be run off and shown to people. That is why, I think, my films are theatrical, and strongly stated, because I can’t believe that anybody won’t fall asleep unless they are. There’s an awful lot of Bergman and Antonioni that I’d rather be dead than sit through. For myself, unless a film is hallucinatory, unless it becomes that kind of an experience, it doesn’t come alive. I know that directors find serious and sensitive audiences for films where people sit around peeling potatoes in the peasant houses – but I can’t read that kind of novel either. Somebody had to be knocking at the door – I figure that is the way Shakespeare thought…”** We venture that Ted’s “embarrassing feeling that someone is constantly tugging at his sleeve” when listening to Wagner, merely reflects his own aridity of feeling.

Item Six: The Enemy of History

Adorno and his ilk are the o-so-clever suppressors of the human spirit; naturally Wagner is accused as “not only the willing prophet and diligent lackey of imperialism and late-bourgeois terrorism…[but he] also possesses the neurotic’s ability to contemplate his own decadence and to transcend it in an image that can withstand that all-consuming gaze.” His music, Adorno bleats, is the ‘commodity’ and exchange mentality of ‘high capitalism.’ Oh dear. Perhaps Adorno would rather sit with Brecht, Grass, and the East German artistic cabal that used to lick Erich Honecker’s boots (figuratively speaking), and watch a Maoist staging of Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy, rather than, for example, attend a good production of The Valkyries, Parsifal, or Tristan und Isolde. It is true that Wagner tended towards a nihilistic weltanschauung; to deride him as a Hobbesian ‘apostate rebel’ is a tad rich.

But Adorno comes around, and verifies or identifies the following:

“[Wagner remarked] that, when listening to Mozart, he sometimes imagined he could hear the clatter of dishes accompanying the music. Contemporary attitudes towards the musical inheritance suffer from the fact that no one has the confidence to be so disrespectful.”

“…the characteristic chord with the allegorical rubric ‘Spring’s command, sweet necessity’ in The Mastersingers, which represents the whole element of erotic passion and hence summarizes the whole action…is indeed the epitome of the musical modernity of the nineteenth century, [which] did not exist before Wagner…few aspects of Wagner’s music have been as seductive as the enjoyment of pain.”

“The art of orchestration in the precise sense, as the productive share of colour in the musical process ‘in such a way that colour itself becomes action’ is something that did not exist before Wagner.”

And, writing in exile before Hitler’s final conflagration, there is at last, this insight:

“Anyone able to snatch such gold from the deafening surge of the Wagnerian orchestra, would be rewarded by its altered sound, for it would grant him that solace which, for all its rapture and phantasmagoria, it consistently refuses. By voicing the fears of helpless people, it could signal help for the helpless, however feebly and distortedly. In doing so it would renew the promise contained in the age-old protest of music: the promise of a life without fear.”

(We add that the Verso edition of this book has an excellent forward by Slavoj Žižek, who is inclined to be less dogmatic than Adorno.) All in all, an interesting and provocative read, but ultimately wrong, invariably Dead Wrong!

[* Need you ask? Wagner, Bach, Beethoven and Mozart (with Schubert, Mendelssohn, Handel, Haydn, Chopin, Rossini, Grieg, Puccini/Verdi and Tchaikovsky in close pursuit…)] [**Orson Welles.]Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

0 Comments