Lawrence of Arabia

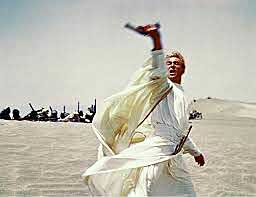

"The trick is not MINDING that it hurts."

(Dir. David Lean) (1962)

Despite Lesley having almost invariably impeccable taste, we strongly disagree with her charge that this is the Worst Movie of all Time. Dare we suggest L was prejudiced by the abundance of sand, the monolithic presence of her beloved Peter O’Toole, and the undeniable fact this is a ‘blokes’ picture’?

Long (few films these days have an overture, an intermission, an entr’acte) but not overlong (compare and contrast The Hobbit), this is film history on an heroic scale, focusing on T(homas). E(dward). Lawrence’s fostering of the revolt in the desert by numerous squabbling Bedouin tribes, against the casual disregard of their Turkish overlords in the dying days of the Ottoman Empire.

Whilst the British expeditionary forces were equally disdainful of the Arabs, their eyes turned towards the western front in the Great War, Lawrence had the perspicacity, the understanding of Arabia and an instinctive feel for opportunity, to strike a decisive blow against the enemy whilst outgunned, out-manned and out resourced. He understood, as Peter O’Toole says as Lawrence in the film, that the Arabian ‘desert is an ocean in which no oar is dipped, and on this ocean the Bedu go where they please and strike where they please.’

Lawrence understood the disparate group of people the rest of the world called Arabs, though he was frequently frustrated by them. In Seven Pillars of Wisdom, he said they “were a people of spasms, of upheavals, of ideas, the race of the individual genius. Their movements were the more shocking by contrast with the quietude of every day, their great men greater by contrast with the humanity of their mob. Their convictions were by instinct, their activities intuitional.”

They had a moment in their long and charged history where they could shine…and either they blew it, or others, as usual, blew it for them. It remains one of the most important issues for humanity – how do we reconcile the passion of men? Without killing them all, that is, as we are wont to do at times, imaging ourselves as gods?

David Lean and his crew spent over a year, what must have seemed an eternity, in the desert. The Arabian landscape is challenging and extraordinary and Lean is said to have drawn some inspiration from the desert scenes in John Ford’s classic The Searchers.

Together with Peter O’Toole, the desert is the star. Lean wrings every dramatic drop from the landscape. There are the opening scenes of Lawrence’s journey to find Price Faisal. There is the famous entrance of Omar Sharif at the well. There is the crossing of the Nefud desert en route to attack Aqaba, sneakily, from the land, where we have the sterling quarrel between Lawrence and Sherif Ali (much derided by P’s better half elsewhere) about going back to rescue the stranded Gasim and the moment when he returns from God’s anvil, having saved the wretch from certain death, a moment to melt (almost) anyone’s heart.

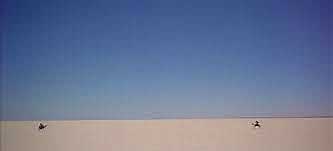

The art direction, the score (and the period songs), the cinematography, are a dream. It must be seen at a cinema, where it seems to be painstakingly painted on the screen. Consider, for example, the early scene changes from Lawrence’s dark little map room, to the officers’ mess, to Mr Dryden’s superb office, where Lawrence says that going into the hellfire of the Arabian sands is ‘going to be fun’, to a desert sunrise that dissolves to a grand vista of mountainous sand dunes in an impossible, unworldly land scape, two camels and their riders a speck on the horizon. This to the sweeping, soaring music of Maurice Jarre as conducted with Sir Adrian Boult, imitated but never matched, let alone bettered.

The script is literate and informed, with well-rounded characters, occasionally straying into caricature. Michael Wilson supplied the history and politics; Robert Bolt the dialogue and a few touches emphasising Lawrence’s essential strangeness and suggesting his ambivalence in personal relationships.

There is an interesting array of performances. Peter O’Toole annoyed some with his playing but if you consider it seriously, he does very well portraying such a scratchy, oblique, tormented character, who is so uncomfortable in his own skin yet who aspires to greatness of the most flamboyant kind. T.E. was more of an insider than Bolt writes him and it is fair to say the overall production values have a deifying effect, but O’Toole’s Lawrence is neither statue nor puppet. What it amounts to, at the end of the so-called Golden Age of Film, is an old fashioned Star Turn. (And nil nisi bonum).

Omar Sharif is charismatic as Sherif Ali, Lawrence’s second banana. Anthony Quayle is solid and stolid as Major Brighton. Anthony Quinn, the all purpose ethnic, is wonderfully thorny and earthy as Auda, the Howeitat chieftain.

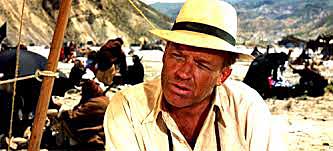

Jack Hawkins is terrific as a wily General Allenby, constantly declaring himself a simple soldier yet exploiting the inspirational Lawrence for all he’s worth.

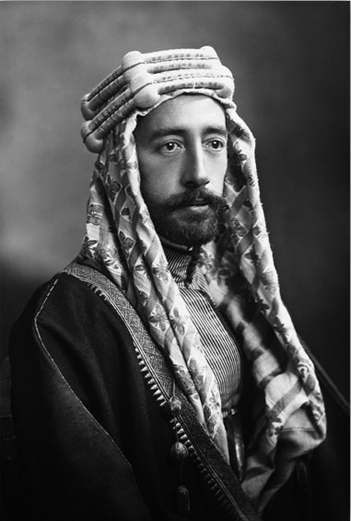

Alec Guinness had a surprisingly close resemblance (though paler) to the man who would become Faisal I, King of Iraq. Peter Sellars had great fun doing the Guinness walk as Faisal, but truth be told, it is a good portrayal of a lofty warrior king with a cunning sense of advantage. One great moment in the film comes during the parley over the spoils after the fall of Damascus, when Faisal says, evenly, of Lawrence that we (the Arabs and the British) “are both glad to be rid of him, are we not?” Yet he also says to the departing figure, without irony, “What I owe you is beyond evaluation.”

In fact, you can never keep strict accounts when dealing with politics in the middle east. By 1920, Faisal was ejected from Syria, without any strong opposition from General Allenby. Lawrence intervened and ensured Faisal had a throne in Mesopotamia, with the British pulling the strings. Faisal out-manouevred them and gained independence for what was now called Iraq (being created, along with Syria, in the Sykes / Georges-Picot carve up of the Levant and points west), only to lose patience with his subjects and pass away in a luxury hotel in Switzerland in 1933, aged 50.

In retrospect, this is a shame, given Iraq’s benighted history since then. However, as is implicit in the film, all gains in war are fleeting, the parties neglecting to remember Clausewitz’s famous dictum that ‘an object should be relinquished when its value was outweighed by the cost of its gain.’ In any case, the historical aspects of the film are very flimsy indeed. The grudging statement, made by Hawkins as Allenby on the steps of Westminster Abbey, to the effect that the revolt in the desert played a decisive part in the middle eastern campaign, is pretty much a load of codswallop. Plenty of Arab tribes stayed with the Turks, who happened to be bugging out of Arabia in any case, as the Ottoman Empire dissolved.

Claude Rains is suave as Mr Dryden from the Arab Bureau. Arthur Kennedy as Jackson Bentley (a sort of Lowell Thomas) reprises his knowing and cynical reporter from Elmer Gantry. Jose Ferrer is wonderfully creepy as a Turkish Bey with eyes for Lawrence. Various supports mug and leer but we commend Michel Ray and John Dimech as Lawrence’s servants/acolytes, Zia Mohyeddin as a guide and I. S. Johar as Gasim.

In the final analysis, despite the carping about accuracy and a vague sense of over-ripeness, Lawrence of Arabia is a wonderful elegiac film, an exemplar, in fact, of old fashioned epic film-making.

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

1 Comment