Maybe we should Bring Back the Noose?

Capital Punishment

On 3 February 1967, serial robber Ronald Ryan, convicted of the felony murder of a gaol warder at Pentridge Prison, was hanged in Victoria. 50 years after Ryan, the last man in Australia to swing, new calls for abolition of the death penalty abound. Some 141 countries have either abolished or suspended indefinitely the penalty, or limit it to war crimes, the remaining 57 still applying it to serious crimes. 10 October 2017 was the 15th “World Day Against the Death Penalty.” (In Reversal of Fortune, the Alan Dershowitz character says of the death penalty, “that’s no penalty, you’re Out Of The Game!“)

Recently, the President of the SA Law Society, in a Media Release, asserted that “…the death penalty robs people of the opportunity to rehabilitate, reform, and contribute to society.”

Arthur Koestler wrote a detailed, thoughtful, impassioned and somewhat colourable argument (Reflections on Hanging, 1956) against the noose. The modern trend shows that his views have prevailed. But was he right, or always right?

As he himself conceded, his three months in a Spanish prison awaiting execution during the civil war informed his outlook:

“I have stated my bias. It colours the arguments in the book; it does not affect the facts in it, and most of its content is factual. My intention was to write it in a cool and detached manner, but it came to naught; indignation and pity kept seeping in.”

Koestler begins with a highly charged review of the history of hanging in England (this Part is entitled “Tradition and Prejudice”). He has a fine time citing various lush historical barbarities of the English (Punch and Judy’s hangman; the ‘Bloody Code’ which prescribed death for dozens of fairly benign offences; Pierrepoint’s Assistant Allenby with his pub ‘The Rope and the Anchor;’ the black cap; the Tyburn tree), and he comments with an unfair inference: “Hanging is quite all right for Englishmen; they actually seem to like it; it is only the foreigners who cause trouble. The outsider appreciates neither the clean fun, nor the solemn ritualistic aspect of the procedure, nor the venerable tradition behind it.” He refers to the ‘national disgrace’ of public holiday hangings, the debauchery and mess of bungled drops, and concludes that “they were outbursts of a collective madness, a kind of medieval St. Vitus’s dance.” This diagnosis of a national pathology is akin to that advanced by filmmaker Michael Moore in Bowling For Columbine, where he considers the American obsession with the right to bear arms and identifies a national malaise, with more justification than Koestler’s piece.

(Obviously the Bloody Code was conceived in panic, in the shadow of the tremendous social change of the Industrial Revolution, and without a standing police force. Hence juries tended to acquit where the mandatory penalty was disproportionate to the offence.)

Next, Koestler refers to the notorious and unsatisfactory case of Derek Bentley, a miscarriage of justice that concerns flaws in the process leading to guilt, rather than mode of punishment, and then he accuses the English Common Law, and English Judges, of inhumanity. He quibbles over a mistake made in the course of the 1948 House of Lords debate and claims the error as evidence of the Law Lords’ “amazing ignorance of social history…a characteristic feature of their mentally inbred world.” Whilst conceding the comparatively enlightened manner in which the adversarial system guards against error in the determination of guilt, yet he goes on to claim, memorably, that the “preposterously savage system…[of the] English criminal law is a wonderland filled with the braying of learned asses.”

Whilst savouring such rhetorical blood in his own mouth, the author proceeds to pointlessly touch upon the pillory and other forms of corporal punishment. Whilst Koestler doubts the evidence of a deterrent effect (of which more later), he agrees with Cesare Beccaria that “legal barbarity begets common barbarity,” a neat and pungent phrase uninformed by evidence. The concluding first part of his historical review contains two assertions which it is illuminating to juxtapose:

“The terror of the French Revolution preserves in retrospect the grandeur of a tragic but essential chapter of history. The terror of the Bloody Code was wanton and purposeless, alien to the character of the nation, imposed on it, not by fanatical Jacobins, but by a conspiracy of wigged fossils…the criminal was for them nothing but a bundle of depravity, who cannot be redeemed and must be destroyed.”

And:

“English law is based on tradition and precedent. I hope that this – necessarily sketchy – excursion into the past may have dispelled some of the unconscious preconceptions which cloud the issue, and will help the reader to consider the problem of capital punishment against its historical background, with an unprejudiced mind.”

Next Koestler attempts to demonstrate that the deterrent effect of capital punishment is a fallacy. His first proposition is that hanging has not deterred murderers in the past, a completely true and almost completely empty statement. Second, the surmise that “the range of hypothetical deterrees…is narrowed down to the professional criminal class”, as murder “is a crime of amateurs, not of professionals.” Thirdly, the number of offenders in previous capital crimes diminished after abolition (which ignores recidivists, relies largely on inferences drawn from notoriously unreliable criminal statistics, and also assumes cause and effect.) Next, that the horrors of public executions did not jolt, so why would those conducted behind closed gates? To which we may say, even accepting the assertion, that it is gainsaid by the clamour attending the deaths of Bentley and Ryan.

In Part II of his book, Koestler examines the Law by reference to various principles, case histories, and of course the philosophy of determinism (as a good Marxist would). It is no exaggeration to claim that these chapters add approximately nothing to his argument. He re-visits the argument against deterrence, ignoring that the converse position requires proof of a negative. He ignores the fact that any deterrent effect is often lost because of excessive delays between verdict and sentence. And his point that the rigidity of hanging for murder renders it problematic, whilst sound, evokes the response that reform to allow a more elastic, discretion-based approach, perhaps resting the final determination in the hands of both judge and jury, might well enhance its effect.

For what is served by condemning a man for heinous crimes to imprisonment for life, with no possibility of parole? To catch the fox and put him in a box and never let him go? Whereas death can be a form of redemption and release, and reverence.

As to retribution – we must face the fact that this impulse, that of vengeance, is the most powerful argument for the noose. Koestler recognises this, and deals with it by saying “If, guided by vengeance, we punish the criminal, then we ought also to punish the alcoholic father, the over-indulgent mother who made him into what he is, and his parents’ parents, and so forth, along the long chain of causation back to the snake in Paradise. For they all, including teachers, bosses and society at large, were accessaries to the crime, aiding and abetting the act long before it was committed.” This is the absurd logic of determinism. As for free will, Koestler seems to regard it in the Christian sense as an argument from design, rejecting its aptness to capital correction accordingly. This makes no sense. His conclusion is that “the death penalty, by its very nature, excludes gradings of culpability.” In over 100 pages of his tract, Koestler never mentions victims of murderers, or amplifies his reference to degrees of culpability.

The polemic finishes with the most cited, and most specious, contention in favour of abolition: “Innocent men have been hanged in the past and will be hanged in the future unless either the death-penalty is abolisheds or the fallibility of human judgment is abolished and judges become supermen.” Of course, but the argument from miscarriage is a grumble about erroneous process, not outcome. A jury is likely to be more careful in returning a guilty verdict in a capital case. Legal aid is bound to beef up to eliminate discrimination against poor defendants in such a case. And as to the so-called irreversibility of the noose, ask Henry Keough if a life sentence in prison after a dodgy trial is so great. (On the other end of the spectrum, one might have asked Ian Brady, if life in prison, contemplating the anathemas called down upon his head by his conduct, is preferable to the short drop. As Nietzsche said, “There is a certain right by which we many deprive a man of life, but none by which we may deprive him of death; this is mere cruelty.”)

Finally, we get Koestler’s attack on methodology. It is undoubtedly true that executions go awry, but a quick and relatively humane form of death should not be beyond human ingenuity.

Koestler’s piece is well written but not well reasoned; sets up straw men to knock out their stuffing; and reasons from his own partisan point of reference. Whilst it is eloquent, and perhaps legitimate, to say that some proponents of the death-penalty “believe that legal murder prevents illegal murder, as the Persians believed that whipping the sea will calm the storm“, such a statement represents an overreach that might satisfy the committed abolitionist, but coldly and thinly, fails to persuade the free-thinker.

Christian religion initially promoted the death penalty heavily, relying on literal interpretations of the testaments. Later, the church joined the charge against it. With increasing relativism and secularisation of society, it now may return. The polls bounce about the place on the matter, and at present there is no political push in most parts of the Anglosphere for a return. In Hanging in Judgment: Religion and the Death Penalty in England from the Bloody Code to Abolition (1993), the author (with the unlikely name Harry Potter) states that it is “almost inconceivable that so long as British society remains broadly Christian, the death penalty could be reintroduced.” On the other hand, what is inconceivable before does not remain so in perpetuity. Consider this view: “Abrogation of capital punishment and it’s obliteration from the law, would be a great folly. In the human rights perspective, concretising the human rights of the criminal (perpetrator of a particular offense attracting Capital punishment) by negating Human Rights of the victim is again a murder of justice.” (Henrietta Newton-Martin, International Rights Lawyer).

But can the penalty be wielded in the appropriate case, without loss of charity, without barbarity, without submission to nascent human blood-lust? Without the trap of attempting to legislatively define capital cases, might we reserve the death penalty to those cases where there can be no credible argument that the degree of malignance and barbarity qualifies them?

Whom then would you hang? Let’s consider what might be appropriate cases.

Travers, Murdoch and the 3 Murphy Brothers

On 2 February 1986, these 5 men abducted, bashed, tortured, raped and killed nurse & beauty pageant winner Anita Cobby.

Wikipedia records that “The five men charged, who later all pleaded guilty or were convicted of the murder, had over fifty prior convictions for offences including armed robbery, assault, larceny, car theft, breaking and entering, drug use, escaping lawful custody, receiving stolen goods and rape.”

Wikipedia records that “The five men charged, who later all pleaded guilty or were convicted of the murder, had over fifty prior convictions for offences including armed robbery, assault, larceny, car theft, breaking and entering, drug use, escaping lawful custody, receiving stolen goods and rape.”

These perpetrators are all alive and living at the Queen’s pleasure.

Who else?

They murdered at least 12 young women over a 20 year period.

Wikipedia reports “At least eight of the murders involved the Wests’ sexual gratification and included rape, bondage, torture and mutilation; the victims’ dismembered bodies were typically buried in the cellar or garden of the Wests’ Cromwell Street home in Gloucester.”

Fred topped himself in prison, leaving a note that he was “in perfect peace.” Rosemary continues to proclaim her innocence.

Bronson Blessington, Matthew Elliott, Stephen ‘Shorty’ Jamieson, Wayne Wilmot and Carol Arrow

On 8 September 1988, these 5 homeless people decided “Why don’t we get a sheila and rape her?” Wikipedia states that 20 year old Janine Balding was that sheila. She was abducted from a railway station car park, “partially stripped of her clothing and raped at knifepoint by Blessington, Jamieson and Elliott…On arrival at Minchinbury, she was again raped. She was then dragged from her vehicle, gagged with a scarf, hog-tied, then lifted over a fence and carried into a paddock by Blessington, Jamieson and Elliott. She was then held down and drowned in a dam on the property.”

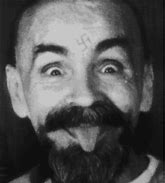

Charles Manson

The head of the Manson Family who directed the murder of 7 people in the summer of ’69 (and who committed 2 other murders).

He was sentenced to death but in 1972 California abolished capital punishment, so he lived to the ripe old age of 83.

Wikipedia reports that at one of his many parole hearings, “The panel also noted that Manson had received 108 rules violation reports, had no indication of remorse, no insight into the causative factors of the crimes, lacked understanding of the magnitude of the crimes, had an exceptional, callous disregard for human suffering and had no parole plans.”

Jeffrey Dahmer

This fellow received a sort of capital punishment – he was murdered by another inmate. Wikipedia notes that Dahmer “committed the rape, murder, and dismemberment of 17 men and boys between 1978 and 1991. Many of his later murders involved necrophilia, cannibalism, and the permanent preservation of body parts—typically all or part of the skeleton.”

The Moors murderers

Ian Brady and Myra Hindley sexually assaulted and killed 5 children in the mid 1960s. Both lived to old age.

The Snowtown Killers

John Bunting, Robert Wagner, and James Vlassakis tortured, killed and stored 11 victims in barrels at a disused bank vault in Snowtown in the 1990s.

Wagner at least was a vigorous supporter of capital punishment. Wikipedia cites his statement from the dock on being sentenced to life: “Paedophiles were doing terrible things to children. The authorities didn’t do anything about it. I decided to take action. I took that action. Thank you.”

Letalvis D. Cobbins, Lemaricus Davidson, and George Thomas

They were all from Knoxville, by way of Heartbreak. They all had multiple felony convictions.

Convicted for the car-jacking, rape, torture and murder of 21 year old Channon Christian and 23 year old Hugh Newsom, in 2007, Wikipedia records that “Christian died after hours of torture, suffering injuries to her vagina, anus, and mouth in repeated sexual assaults. Bleach was poured down her throat and used to scrub her body while she was alive in an attempt by her attackers to remove DNA evidence. She was bound with curtains and strips of bedding, her face covered with a trash bag, and her body stashed in five large trash bags. These were placed inside a residential waste disposal unit and covered with sheets. The medical examiner said there was evidence that Christian slowly suffocated to death.”

Davidson was sentenced to die by lethal injection, but 10 years on, he is alive, on death row in Tennessee.

Jack the Ripper

Over 9 weeks in 1888, 5 women were mutilated with a knife. These crimes (and some others) have been attributed to one ‘Jack’, who wrote to the police: “I am down on whores and shant quit ripping them till I do get buckled.”

Dudley Davey

In 2016 he raped and murdered nurse Gayle Woodford on South Australia’s APY lands, a remote aboriginal community, while Woodford was answering a late-night callout. Davey stole her ambulance, too. ABC news reported that “Davey had a history of violent assaults against women, which had increased in severity over the years.”

On 28 April 1996 at Port Arthur, Tasmania, he murdered 35 people and wounded some 20 others with an armalite rifle and a semi-automatic. First given a rifle at 14, he took to shooting animals multiple times, or firing randomly into traffic (à la Targets). Sentencing him to life imprisonment, Chief Justice Cox stated: “I have no reason to hope and every reason to fear that he will remain indefinitely as disturbed and insensitive as he was when planning and executing the crimes of which he now stands convicted.”

“Not long ago I was much amused by imagining—what if the fancy suddenly took me to kill some one, a dozen people at once, or to do some thing awful, something considered the most awful crime in the world—what a predicament my judges would be in, with my having only a fortnight to live, now that corporal punishment and torture is abolished. I should die comfortably in hospital, warm and snug, with an attentive doctor, and very likely much more snug and comfortable than at home. I wonder that the idea doesn’t strike people in my position, if only as a joke.” – Dostoevsky, The Idiot.

Adrian Ernest Bayley

He raped and murdered 29 year old ABC radio personality Jill Meagher whilst she walked home from a Brunswick pub in the early hours of 22 September 2012.

He raped and murdered 29 year old ABC radio personality Jill Meagher whilst she walked home from a Brunswick pub in the early hours of 22 September 2012.

He has 12 convictions for rape or sexual assault.

Are any of these people likely to avail themselves of, in the Law Society President’s words, “the opportunity to rehabilitate, reform, and contribute to society”?

“Throughout history, it has been the inaction of those who could have acted; the indifference of those who should have known better; the silence of the voice of justice when it mattered most; that has made it possible for evil to triumph.” (Haile Selassie)

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

2 Comments