Modern Art Theory

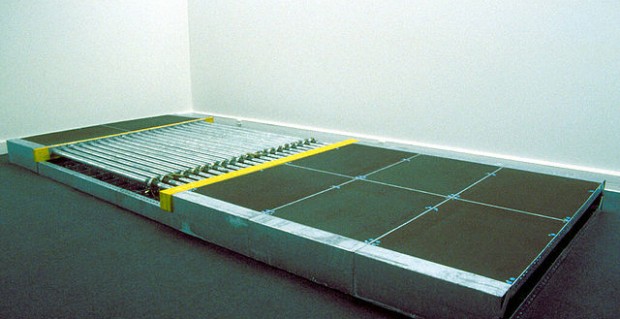

(Bosslet Public Art, 1988)

Here’s a a link (see below) to a highly entertaining and rather persuasive rant from Paul Joseph Watson, about the essential bogus nature of much modern art. It’s a fight no-one can win, of course – you can debate aesthetics till the sun blows up.

But it is true that expensive modern art carries a strong whiff of elitism about it. Style is loosed from substance. Then style is discarded, as a rhetorical flourish. What is left? Modern art. In a piece entitled “The Perils of Painting Now”*, Jed Perl reports, possibly ironically:”A few years ago, the Luxembourg & Dayan gallery hosted a show of “Unpainted Paintings,” featuring works made using Kool-Aid, urine, fire, and silver foil, on supports that included a piece of shag rug. Massimiliano Gionio, the New Museum curator who organized the retrospective of Albert Oehlen’s work, which is a mash-up of glib pop culture references and scabrous abstract brushwork, writes that the artist’s goal is “to paint while at the same time denouncing the inadequacy of painting.”‘ [The New York Review of Books, September 24, 2015, p.55.]

Only deep in the bowels of bureaucracy do you encounter torments to language obtaining from the world of contemporary art. Terms and phrases pack and move on, quick as Harold Hill skipping town. Installations are now ‘site specific’; Bridget Riley’s Static III with its diagonal lines of black dots on white, is, according to the artist, “a mass of tiny glittering units like a rain of arrows.”

In honouring the worst public art in Britain, Stephen Bayley observes that “Public art may be hard to define, but it is always easy to detect: shrieking for attention, but pitiably inarticulate.” [“Public Offence” Spectator 6/2/2016.] This is where the florid verbiage comes in: as a cloak for a thief. How thoughtlessly wise Matisse was to admonish embryonic artists to first cut out their tongues!

Contemporary art seems designed to serve the purpose, as Robert Hughes put it, of hanging on a wall, getting more expensive. Today, for example, we read that Jack the Dripper’s Number 17A sold for two hundred million dollars, and Willem De Kooning’s Interchange for three hundred million. A monkey could produce better than these works, but if they please the man who bought them, fair enough: “money spent is money earned.” Roger Scruton memorably wrote: “In a curious way [the modernist establishment, kitsch and pop] belong together; they are the great forms that lie beached on the shore of human leisure as high culture recedes…[which] triggers the quick response of the establishment critic, who knows that he will make no mistake by praising it, for the very reason that no-one, not even the artist, will understand why he does so. To the same cause may be attributed the invasive nature of post-modern art, its tendency to colonize every available inch of floor, wall or ceiling, in order to drive out from our perceptions all that is not art…”

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

0 Comments