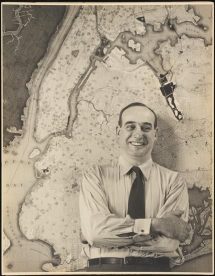

The Power Broker

(Robert Moses and the Fall of New York) (by Robert A. Caro, 1974)

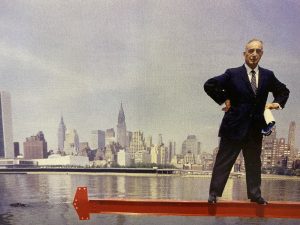

That this brick of a book (well over a thousand pages) about public infrastructure is so compelling is due to, first, its traverse of key decades in the rise of America (1920s to the 1960s); second, the author’s awesome depth of research and keen grasp of his subject; and third, the subject himself: the most famous public official in New York (perhaps America), Robert Moses (18 December 1888 – 29 July 1981), a humanities man, without engineering qualifications, who yet singlehandedly matched the Pharaohs and the Romans in empire building. Under Moses’ forty odd years in power, his list of NYC credits is staggering (this link is not exhaustive: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Robert_Moses_projects) and includes over 650 playgrounds, over 100 state parks, over 400 miles of parkways, countless urban expressways, bridges linking the NYC boroughs, tunnels linking them under the waters, man-made beaches, boat basins and aquatic infrastructure, low rent housing apartments, causeways and dams, the United Nations complex, the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, Shea Stadium, the NYC Coliseum, the Astoria Pool, the 1964 World’s Fair, and a myriad other bits and bobs. He “built public works costing, in 1968 dollars, twenty-seven billion dollars.”

Obviously Moses was the greatest planner (and, crucially, implementer) of public works in the history of the United States, perhaps of the whole modern world. Caro tracks and acknowledges the tremendous achievement, but he also does what few did during the reign of Moses – count the cost. Moses conceded that:

“You can draw any kind of picture you like on a clean slate and indulge your every whim in the wilderness in laying out a New Delhi, Canberra or Brasília, but when you operate in an overbuilt metropolis, you have to hack your way with a meat ax.”

Moses destroyed as fervently as he created. And he did whatever it took, engaging in corrupt behaviour so noxious that he would have faced charges but for the key fact that he never lined his own pockets. Indeed, power was his drug, not love, fame, nor money. As Lord Acton said, “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men.” Robert Moses is a classic example, a perfect specimen, at whose door many floral tributes lie, and for whom the operative word is “lie.” He brooked no arguments; he never changed his plans.

Caro follows Moses from his fairly comfortable youth and student days at Yale and Oxford. While an idealist, he displayed early signs of sharp practice. And after his attempts at public service reform (pursued by him with enthusiasm, naivety and arrogance) left him bruised and blackballed by the New York Tammany machine, he became “scornful…of what he had been.” Forming a deep alliance with NY Governor Al Smith in the 1920s, Moses became not only adept but supreme in the dark arts of governance (persuasion, intimidation, dissembling) – and got his first taste of power. He learned by watching Smith “twist arms, offer incentives and drop, one by one, with matchless guile, the veils from in front of threats.” But Smith had a strong social conscience and tried hard to help the helpless. Moses was less idealistic: he preferred to use power to realise his dreams.

He started on Long Island. Put in charge of State Parks, he wheeled-and-dealt with breathtaking deviousness, flair and diligence. Appropriating, haggling, exploiting the good will, slow wit and altruism of others, he grabbed or re-claimed land and created some 20 major state parks on the island (not Arcadian glades that some of his old-money patrons desired, but ‘working parks’ which were often “banal“) – with major expressways or parkways to access them from the boroughs to the west. For a man that never learned in 93 years to drive, he enabled New York over time to be engulfed by the automobile: creating great new expressways through his autonomous vehicle – the commissions and authorities gathered under the heading ‘Triborough Authority,’ which became (through private bonds and public tolls) richer and more powerful than the City of New York itself. He used that power to blackmail (and at times avenge) the so-called powers-that-were. Sheer talent and hard work were not enough: at some point, this remarkable man, who had long studied and tried to repair local government, concluded that the only way was to skirt, ignore, and supplant it. With Smith’s complicity, he tweaked legislation and executive action to ensure that he kept total control of planning, finance, acquisition, construction, and remuneration. He made a quango not dependent on public finance. He became a one-stop shop, if you wanted any development done in NYC.

Along the course of such development, he rode roughshod over the rights of landholders. He evicted (sometimes prematurely and capriciously) a quarter of a million poor people (many African-Americans and Hispanics, not his preferred people) from rent-controlled apartments and left them to find other accommodation. He ignored the law, often ordering his construction crews to demolish before an injunction was granted, sometimes even afterwards. He would misrepresent the costs of a project, knowing that by the time it was underway, elected officials were compromised and powerless not to appropriate further funds. “Misleading and underestimating, in fact, might be the only way to get a project started.” He hid inconvenient facts, demonized opponents or even those with legitimate questions, and viciously used and abused the power of the press, especially of his friends at the New York Times and The Daily News. Having made one disastrous run at the Governorship in 1934, he instead skirted, ignored and supplanted democracy. But he also out-thought and out-prepared adversaries and generally bested them in argument (and invective). It is significant that, with no driver’s licence himself, he turned his limousine into a mobile office, working and planning and plotting as he was chauffeured all over the City and State of New York: he was simply more driven than anyone else.

NYC Mayors, from the formidable Fiorello La Guardia to the dilettante John Lindsay, tried to control or eject him: they failed. Governors, from Franklin D. Roosevelt to W. Averell Harriman, tried to do so: they failed. (FDR even tried when he became President in 1933 – he failed, asking an aid, “Isn’t the President of the United States entitled to one personal grudge?” to be told “No“). Moses would threaten to resign, knowing he was indispensable, which for quite some time, was true. He would threaten to go to the press. He would call in all his rent & fee seeking pals and partners in the unions, banks, construction companies, et al to write memos, make calls and spread smears. He would bully anyone. Once Triborough was established, it was financially independent and all-powerful, and virtually untouchable until bad decisions and decay started to afflict Moses’ built legacy, lost fights tarnished his reputation and hold on a new generation of the pressmen, age weakened his grip, and a Governor whose wealth and ambition put him above everything, prevailed: Nelson Rockefeller.

The Power Broker is a superb study of politics and power, and a biography that brilliantly proves Solzhenitsyn’s dictum, in The Gulag Archipelago, that “the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being.”

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

0 Comments