Twenty Thousand Roads

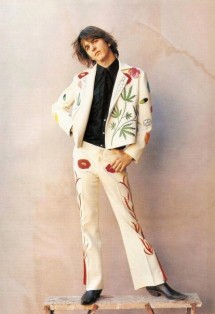

"Just because we wear sequinned suits doesn't mean we think we're great..."

Twenty Thousand Roads: The Ballad of Gram Parsons and His Cosmic American Music (by David N. Meyer) (2008)

Never meet your idols. Gram Parsons didn’t give us a chance, checking out at the age of 26 in September 1973. An insouciant, genial, audacious, southern-fried poor little rich boy, his devotees can credibly claim he fomented or drove the cross-over of American country-rock, a genre that, like its sires, has produced some inspired and much insipid music.

Written, or rather, over-written*, in the excessively familiar, repetitive and talky style of books on popular music, Meyer has done his homework and manages to create a rich world of talented wastrels, blooming in the Summer of Love and withering in the following seasons, along the way creating what is described as Cosmic American Music. Meyer is deeply immersed in the lineage of popular musical forms and tells us much that we knew and much that we didn’t. It is a big, windy book but still full of interest.

Fundamentally, here is a traditional biography, and hence valuable, for amid all the hype and gloss there are facts and impressions (and at times, unnecessary, almost Dickensian, detail) which go to portray a man most readers will have never met, whose artless yet beguiling voice travels down to us from the ether, thanks to various rough and polished recordings.

Born Ingram Cecil Connor III in Winter Haven, Florida on 5 November 1946, to Avis Snively, daughter of an orange grove magnate, and Ingram Cecil “Coon Dog” Connor (a couple of legendary drunks who died well before their time), he adopted the surname of his wayward stepfather, Robert Parsons and shuttled between Georgia and Florida, spending his ample pocket money on records, tape recorders and eventually, musical instruments. He was ‘converted’ by seeing Elvis Presley perform at Waycross, Georgia in 1956, and never looked back.

At school, at college and later, shuffling in and out of a succession of bands with nary a backward glance (“The Pacers”, “The Legends”, “The Rumours”, “The Vanguards”, “The Shilohs”, “International Submarine Band”, “The Byrds”, “The Flying Burrito Brothers”) Gram was the self-assured and sanguine big enchilada of these bands (apart from the Byrds, where an artistic power struggle between him and Roger McGuinn was refereed and then infiltrated by Chris Hillman, during the making of the seminal 1968 album Sweetheart of the Rodeo). But a certain diffidence, dare we suggest hauteur, undermined his ambitions. Meyer’s statement is apt – Gram “avoided success with great dexterity, turning once-in-a-lifetime, career-making breaks into amusing go-nowhere anecdotes” (p. 119).

Parsons struggled with his work ethic. That suggests a combination of a spoiled upbringing, the comforting fallback of a family trust fund paying a healthy annual dividend, a natural tendency to goof off, addiction to increasingly potent drugs and pharmaceuticals, life in L.A. generally, his chaotic home life, a doomed (but, for a time, mutual) limerence or man-crush with notorious drug-fiend Keith Richards, and assorted moody friends and family, a good number of whom were similarly marked for premature release from life.

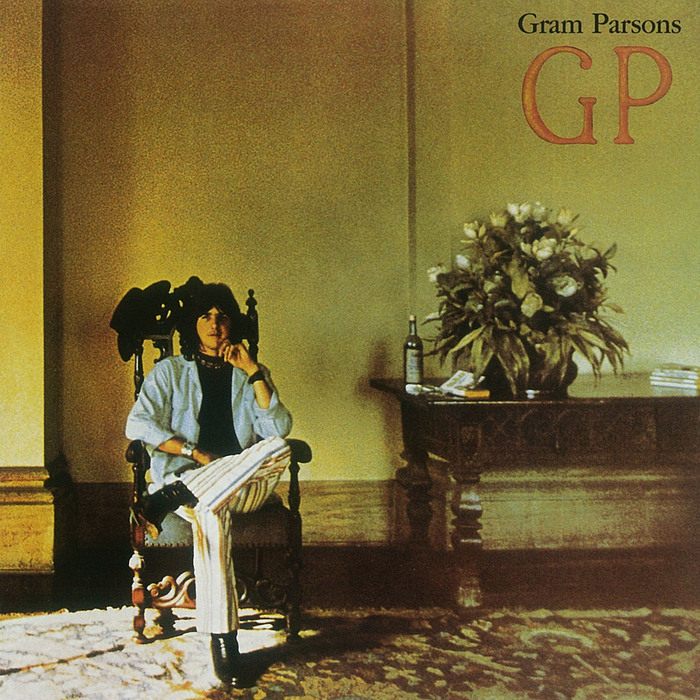

But it also appears to reflect the fact that he thought deeply about what he was trying to do, and worked like a navvy to achieve a genuine breakthrough in the cross-over between pure country music and pop. Such a fusion is not easy, and the fact that he failed (which is why we have Poco, The Eagles, New Riders of the Purple Sage and the ‘twangier’ aspects of the Doobie Brothers) shouldn’t devalue his effort. Whilst The Varnished Culture must admit that the charms of Sweetheart of the Rodeo** leave it cold, GP and Grievous Angel have some lovely things on them, commendable to posterity: “Still Feeling Blue”, “We’ll Sweep Out the Ashes in the Morning”, “Cry One More Time”, “How Much I’ve Lied”, “Cash on the Barrelhead”, “Love Hurts”, “Hickory Wind” and “In My Hour of Darkness.”

These fine albums were commercial flops, and the second had not even been released when Gram Parsons upped and died, from a probable concoction of pills, booze and morphine sulphate on 19 September 1973. Meyer suggests his death was “a classic relapse overdose.” There is a lengthy discussion concerning those with some responsibility for his premature death but, as in the case of another singular star who died young, John Belushi, the cadaver had no-one else to blame. One of his treating doctors is quoted as saying “There’d be times when he’d be taking overdoses where he’d look appalling.”

As befits all legendary doomed youth, Gram’s corpse was stolen and immolated (against the wishes of his family but per his own wish, expressed only months earlier at a fellow musician’s leaden, formal funeral) – his reputation secure and his soul safe at home at last.

This is not the best book about a notable musical figure who lived fast and died young, not by a long chalk, but we are glad to have read it. It did enlighten and inform us on several fronts and it helped us get to know the backwoods boy so special that everyone found excuses for him. It’s a slog of a read but worth it.

[*E.G. Clunky prose is evident in these excerpts: “In Gram’s case, all the archetypes are true but none tell the truth. In tracing his story, I discovered that the man himself, as befits a walking catalog of archetypes, was an archetype magnet of the first degree. And so he posthumously remains” (p. xiii). “These knowing few knew too much to become ideologues. They listened to everything not to determine a moral hierarchy but to discover how primitive American musical forms nourished one another. And because they dug it” (p. 152). “Gram’s fascination [with UFOs] seems an offshoot of his interest in various spiritual quests, and tied to his theological bent. Plus, marijuana was an undeniable factor” (p. 170).] [**The Varnished Culture went back afterwards and gave Sweetheart of The Rodeo another spin. A stuttering mishmash of Tennessee, Bakersfield, Texas and Nashville, the stand-outs are “You Don’t Miss Your Water,” “You’re Still on My Mind,” “Hickory Wind,” “One Hundred Years From Now” and “Life in Prison” – which Merle Haggard song here is oddly reminiscent of “My Love For You (Has Turned To hate)” – are lush enough, but the hippie-billy vocals are toughened-up and suitably bitter. As Meyer points out (p.259) country rock “would slowly devolve, through ever-slicker production and more self-consciously “sensitive” singing, into a blander, cleaner, more accessible, more commercial, and gutless product.” (And by the way, Jo Mora’s 1933 album cover is a classic.)]Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

1 Comment