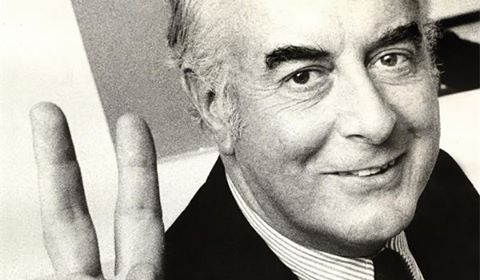

Vale Gough Whitlam

Vale Edward Gough Whitlam (11 June 1916 – 21 October 2014)

After the Australian Labor Party failed to win the cliffhanger federal election of 1961, in which it won no seats in Victoria, the leader, Arthur Calwell, failed to quell the left’s hatred of aid to non-government schools that lost it a stack of votes among working class Catholics.

Eventually, on 8 February 1967, having not held the reins of power for the better part of a generation, federal caucus turned to Whitlam, who stared down the Victorian State Conference in June of that year (saying of their electoral death wish “Certainly the impotent are pure”) and took Labor to a competitive defeat in 1969, saying “I’m rather disappointed in the Prime Minister (Gorton). Before this campaign we had a distinct understanding – that he wouldn’t tell any lies about me, if I didn’t tell the truth about him.” When heckled and asked for his policy on abortion, he replied “In your case it ought to be retrospective.”

Whitlam became Prime Minister on December 2, 1972 (Austerlitz), defeating the ‘Tiberius with a telephone’, William McMahon. In retrospect, the result seems inevitable; Labor under Whitlam seemed fresh and ready to govern. Its campaign slogan, “It’s Time”, together with a catchy jingle, and the leader’s messianic speech at Blacktown Civic Centre on November 13, caught the zeitgeist. In fact, Labor won by a relatively slender margin of 67 seats to 58. It had not been in government federally for 23 years. Nobody in cabinet had ministerial experience. Discipline was not its strong suit – Whitlam observed, “I don’t care how many prima donnas there are in the Labor Party, as long as I’m the prima donna assoluta.”

His government initiated a series of changes and legislative reforms, many of which have endured and gained wide acceptance. On foreign policy, his efforts were decidedly mixed: he recognised, as did President Nixon, the importance of a rapprochement with China; he attempted, in a somewhat ham-fisted way, to ‘broker’ peace negotiations between the US and North Vietnam (but put up blocks against Vietnamese refugees); he apparently did nothing to discourage President Suharto from annexing East Timor; he rather pressured New Guinea into premature independence; he re-established diplomatic relations with North Korea and gave de jure recognition to USSR sovereignty over the Baltic States (for this writer, a crimen exceptum).

Domestic governance was also mixed. Medibank has been a success to date, vindicating either economies of scale or socialised medicine. The axing of university fees enabled a few unworthy paupers (such as this writer) to get a degree but did not last (the Hawke Government abolished it early on). After his Attorney General had raided ASIO (March 1973), Whitlam appointed him to the High Court, sacking the head of ASIO and calling a Royal Commission. He passed the Family Law Act, allowing for divorce based on 12 month’s separation, the Trade Practices Act and the Racial Discrimination Act, key pieces of legislation that endure.

Symbolism is a worthy part of governance. Whitlam took protean and symbolic steps to recognise aboriginal land rights, to implement a national water policy, to drive new enquiries and initiatives into social security, public transport and urban planning. He established the Literature Board and bought Blue Poles.

The critical failure was in finance. Apart from flouting the Thatcherite warning against running out of other people’s money, the government’s methods of raising it, in tight times and with a declining credit rating, were suicidal. On 13 December 1974, the day before the PM got on a plane for an official tour of Europe, Executive Council (not on this occasion attended by the Governor General) gave Rex Connor permission to raise loans of billions of petro-dollars via Mr. Tirith Hassaram Khemlani, a likeable though dubious man.

This authority was revoked on 7 January 1975 but Connor kept it alive and in the meantime, Treasurer Jim Cairns gave letters of authority to raise overseas loans with a brokerage fee of 2.5%. He denied this in Parliament and when Whitlam was sent the letters, he had to sack Dr. Cairns. Connor had to go when the Loans Affair became toxic and Whitlam demanded all communications between the Minister for Minerals and Energy and Mr. Khemlani. Connor supplied all that he said was relevant of substance; the Prime Minister tabled the documents; then a cable was leaked from Connor to Khemlani, dated 23 May 1975 (4 months after his authority had been revoked) stating “I await further specific communications from your principals for consideration.” In these words, innocuous in themselves and of no practical legal consequence, lay the death of the government.

A series of events led to the fall. The loans affair robbed the government of an air of legitimacy. This was the premise for an unprecedented defiance of conventions. The Senate was tied after the 1974 election; then the Premiers of NSW and Queensland refused to appoint two casual vacancies nominated by the party to whom the deceased and retiring members belonged. And then, as opposition leader Malcolm Fraser directed, the coalition-controlled Senate did what it had never done: blocked supply.

Sir John Kerr, a little ‘tired and emotional’ at the 1977 Melbourne Cup

The constitutional crisis of 1975 was a war of nerves between the government and the opposition (Whitlam and Fraser, 2 men with egos the size of the Ritz, were the principal agents of the crisis). Government went on and, given a little more time, Gough may well have prevailed. But the Governor General, Sir John Kerr (who had a pretty big ego himself), broke the deadlock on Remembrance Day, 11 November, by dismissing the government, appointing Fraser ‘caretaker’ Prime Minister and directing a general election. Whilst doubtless legally valid; and justifiable with the government, sans supply, about to issue ‘vouchers’ instead of wages, and with Sir John in a cleft-stick by virtue of his need to keep Whitlam in the dark to avoid the possibility of embroiling the Queen in a partisan cage-fight, nevertheless, this executive action seemed precipitous and unnecessary to many; it certainly looked pretty ‘raw’. (Whitlam remarked that it was “the first time a burglar has been appointed caretaker.”) In the election held on 13 December, Labor, already cast as the villain of the piece, was smashed, winning 36 seats to the coalition’s 91.

“Well may we say ‘God Save the Queen'” quoth Whitlam, “…for nothing will save the Governor-General.”

Viewed in the cold light of history, the Whitlam government was a failure, yet an interesting one. As Whitlam later wrote: “all the effort, all the inevitable setbacks, all the obloquy, all the sacrifices…were splendidly worthwhile.” And his personal story is one of honourable success – a permanent place in history as a warrior of modernity and reform, less a helmsman than a re-designer of the ship.

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

1 Comment