Leonardo da Vinci

(by Walter Isaacson) (2017)

We picked up this heavy tome in Washington DC and carried it all the way home. It’s well put-together, beautifully illustrated, and fairly well organised. Whilst Leonardo the Man remains opaque, this book manages to avoid drowning in the sea of speculation, as a disastrous recent work on Beethoven does not.

An apt pupil…Leonardo’s contribution to Verrocchio’s “Baptism of Christ” was the True Angel, the nether Jesus and the background wilderness

Leonardo da Vinci lived and died 500 years ago, and left behind a tantalising body of mostly incomplete work, in particular, some startlingly radical and luminous paintings, fanatically detailed drawings, and thousands of pages from inspired commonplace books. Although his siege engines and tanks and flying machines, and his mathematics, were mostly twaddle, his relics reveal an astonishing, preternatural polymath, a relentlessly inquiring mind, a perfectionist untroubled by deadlines (to paraphrase Douglas Adams, he liked the gentle whoosh as they passed by).

Isaacson has assiduously pored over the evidence and given a modern gloss on the work, a catalogue raisonné that quite often plods but still reaches apt end-points. However, a very silly decision was made to dress the penultimate end-point with a series of bromides fit for the back of old-fashioned printed bus tickets (of which, more later). It is often, if not always, difficult to write about “Genius” and not sound like a gushing student groupie writing an end-of-term essay, and regretfully, Isaacson falls into this snare on occasion (though who could not?). (In a rather dismissive New York Times review – 1/11/17 – Jennifer Senior suggests that Isaacson “hails many of Leonardo’s creations in the same breathless tone with which a teenager might greet a new Apple product.”) There are also passing descriptions of recent works attributed to the great man (which are mostly best ignored – if they are by Leonardo, and we have doubts, they show Leonardo on off-days).

“The most revolutionary and anti-classical picture of the fifteenth century” (Kenneth Clark) – “Adoration of the Magi” (unfinished)

Vinci had an eagle eye, an enquiring mind and boundless patience. In a brief coda, Isaacson mentions Leonardo’s note to himself to “Describe the tongue of the woodpecker.” The utility of this task is obviously highly moot, yet it sums up the artist’s unquenchable thirst, the kind of hankering that gave rise to the phrase “Renaissance Man.”

Whilst the paintings are exhaustively deconstructed, this doesn’t fatigue the reader in the case of Leonardo, for whom enigma was a matter of aesthetics just as much as the close reading of nature. He took painting from its designation of mere mechanical art and elevated it, according to the principles of Alberti and along the lines of later Renaissance dicta by the likes of Vasari. There is a superior psychological resonance and greater representational humanity in his works whether complete, half-done, in prototype, or aborted. There are also seminal drafting and painterly techniques that he made or established. His new approach to perspective and portraiture are striking examples. The organisation in the most famous half-use of a restaurant table in all art, The Last Supper, is a magnificent display of both.

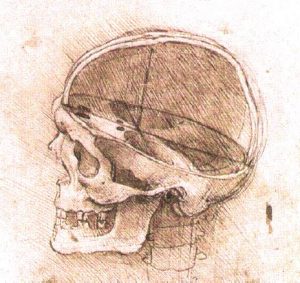

The book also examines Leonardo’s many other interests and obsessions: squaring the circle; the anatomy of beasts and humans and how various of their internal parts work; architecture; geometry; physics; hydraulics; theatrical entertainments; the gay life; the need to eat soup before it cools; the travel of light.

Isaacson puts his central thesis quite nicely in the Introduction: “His scientific explorations informed his art. He peeled flesh off the faces of cadavers, delineated the muscles that move the lips, and then painted the world’s most memorable smile.”

Now for the hard part. Chapter 33 offers a conclusion of sorts. Having deprecated that much-bandied-about medallion, “genius,” he pins it to his subject, with the help of famous philosophers Arthur Schopenhauer and Steve Jobs. Even more haplessly, he finishes with the flourish, “Learning from Leonardo,” where we’re fed 20 aphorisms of a kind which obtain from the more turgid Facebook pages: “Be curious, relentlessly curious…Seek knowledge for its own sake…Retain a childlike sense of wonder…Observe…Start with the details…See things unseen…Go down rabbit holes…Get distracted…Respect facts…Procrastinate…Let the perfect be the enemy of the good…Think visually…Avoid silos…Let your reach exceed your grasp…Indulge fantasy…Create for yourself, not just for patrons…Collaborate…Make lists…Take notes, on paper…Be open to mystery…Try to see the other person’s point of view…” Sorry, that last one popped into our head by accident; it’s one of the thoughts of Kit Carruthers in Badlands. But it seems as valuable as the rest.

We sum up this book by saying it is better to have it than not. In a world saturated with books, this is no praising with faint damns. It is written with confidence, clear, a tad familiar in the American style, opinionated but not lacking in wisdom. It is generally light on context and comparison with fellow contemporary artists (the spat with Michelangelo features) which is a shame. It is therefore not the definitive Leonardo. Kenneth Clark’s 1930s work is probably the best, although now showing its age and dated by the latest research and scientific techniques (although you don’t need an X-ray machine to form a view on the Salvator Mundi or the Monna Vanna).

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

0 Comments