Uncomfortably Close…the Lawyer in the Freezer

This story is one of the many lurid crime sagas that feature in staid and leafy-green Adelaide. And whilst The Varnished Culture staff all have impeccable alibis, this being Adelaide, we are far-away-so-close to the macabre events of 1979 and beyond. Unfortunately, it is one of several local causes célèbre where the jury’s verdict is in question because they may have been led to rely on tainted evidence – not corrupt evidence; just misleading, or dead-wrong.

THE PLAYERS:

Derrence Stevenson, specialist criminal lawyer (the victim);

David Szach, Stevenson’s teenaged boyfriend;

Dr Colin Manock, forensic pathologist, who gave crucial evidence at trial re time of death;

Gino Gamberdella, chiropractor and friend of Stevenson; and

X, a young man who entered an Adelaide legal office and insinuated that Stevenson was in serious, but not urgent, need of medical attention (this the morning after the disappearance, when the accused was meant to be out of town).

THE (PROBABLE) SCENE OF THE CRIME:

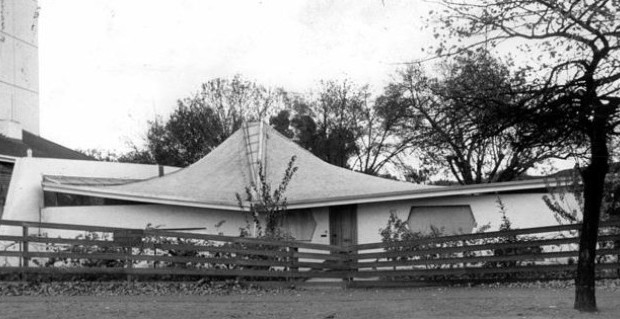

189 Greenhill Road, Parkside: a notorious house on the south side of town – an egregious architectural meld of Jan Utzon and Frank Lloyd Wright, the roof of which was later to become beloved of skate-boarders, served as Mr Stevenson’s home, office, and party-central, in the late 1970s. (See main image).

The building moved from notoriety to infamy in June 1979 when Mr Stevenson, then aged 44, was reported as missing. The word was that police scoured the building, which is as crumpled within as it appears from the outside, but were on the point of leaving, empty-handed, when an officer casually tried to open a freezer cabinet in a small room facing the back of the triangular property. He was unable to do so and on examination, found the unit had been sealed. Once the lid was off, Stevenson was found inside – dead, a bullet wound to the back of his head, his corpse, in a degree of undress, wrapped in garbage bags.

Today Tonight invaded the mise-en-scène one night in an unwelcome attempt to garner footage and a comment from the entirely innocent firm that had acquired the building after Stevenson’s death. It was eventually sold to the Transcendental Meditation Movement, the creation of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (beloved of the Beatles, or some of them), who left for Nirvana around the same time. The building was knocked down in 2008 and the lot remains vacant. Whilst the configuration of the land is apparently consistent with Vedic principles, plans for the site (if any) remain unknown.

FORENSIC AND CIRCUMSTANTIAL ISSUES

Stevenson’s ‘steady’ at the time was 19 year-old David Szach. Szach seems to have been the only suspect in the case. He was charged and convicted by a jury in 1979 and served 14 years of an 18 year sentence. He has maintained his innocence and recently lodged an appeal against conviction, under a new law that allows appeals based on new evidence.

On 5 June, 1979, Dr. Manock attended the freezer room. He observed a body, the subcutaneous tissue of which was still deep frozen, although the unit was not then in operation. His autopsy was carried out the next day. The critical part of his opinion related to time of death, a matter of classic forensic in-exactitude. His conclusion? Death came about 5.45 pm on 4 June 1979, some 24 hours before the police turned the freezer unit off. This is crucial because of evidence Szach was at the house till after 6.40 pm on the 4th. Thereafter, he was on the road to Coober Pedy – 850 kilometres away – in Stevenson’s car. Assuming a lover’s quarrel, that just about tied-it-up for means, motive and opportunity. In recent years however, a number of questions have arisen concerning the reliability of Dr. Manock’s forensic evidence, and an appeal is in the winds, based on new forensic opinion that the time of death presented to the jury may have been ‘shaky.’

Of course, a jury considers all the facts, not just those of the boffins. The jury might have been persuaded of the accused’s guilt without the forensics. But scientific evidence validating those suspicions must, by its very presence, weigh heavily – and two other facts arise, which when one accepts uncertainty over time of death, leave a bad feeling in the bones:

- Witnesses suggested others were present at the Stevenson party-house on the night of 4th June, and several cars were parked outside, including one known to be owned by Mr. Gamberdella, thought to be a ‘procurer’ for Stevenson (he left Australia in the wake of the affair);

- At a little past 8 am on the morning of 5th June, a young man knocked on the door of the Legal Services Commission in Adelaide, wanting to speak to a solicitor about “a crime.” Asked whether he had consulted any solicitor about that, he apparently replied “Only Derrence Stevenson but when I left him last night he was in no condition to act for anyone.” It doesn’t seem that this fellow, ‘X’ could have been David Szach.

What to make of all this? We may never know. Reportedly there have been funding difficulties for the appeal (which may now have been resolved), because Szach served his time, so why bother? But surely the wheels should never stop turning. We have to be sure of guilt, not only to punish or correct, but also to clear the ‘umbrella of suspicion’ hovering over the innocent.

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

5 Comments