The Varnished Culture's Thumbnail Reviews

Regularly added bite-sized reviews about Literature, Art, Music & Film.

Voltaire said the secret of being boring is to say everything.

We do not wish to say everything or see everything; life, though long is too short for that.

We hope you take these little syntheses in the spirit of shared enthusiasm.

Tender is the Night

(by F. Scott Fitzgerald) (1934)

Scott and Zelda, Dick and Nicole – these tempestuous marriages merge in Fitzgerald’s most substantial novel, a complete rendering and realisation of the beautiful people of the cote d’azur between the wars. The author referred to the book as “a confession of faith” in a secular sense and there is a touch of Keats in his portrait of the ambitious Dr Diver and his doomed, chivalrous defiance of the rule against falling in love with your patient. Sheilah Graham justly described Tender as “sheer poetry all through, though the story is not so tightly knit as Gatsby.”*

[* The Real F. Scott Fitzgerald, 1976] Continue Reading →The Seed Collectors

(by Scarlett Thomas).

Copy the Gardener “Family Tree” at the opening of this novel and keep it close at hand. Perhaps you will be more successful than I at keeping the characters apart, remembering who is married to whom, who is whose brother and whether or not this sweaty encounter is adultery. The characters all seem to have the same name and hip “lifestyle”. The confusion is confounded by the chop-change style – in case the reader is not confused enough, incomplete passages of pop-psychology, dialogue and cogitation are interlarded without attribution. Is it Oleander, Clem, Charlie, Ollie, Bryony, Holly, Ash, Pi, Fleur, Skye or Pondscum this time? Bryony’s drunken shopping and eating spree – although it seems to be an admonition against consumerism and gluttony, it is by far the best part in the book.

Continue Reading →Headlong

(by Michael Frayn)

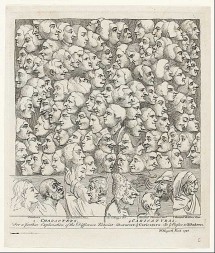

What would you do if you were certain that you had discovered a work of art not so much lost as mythical? A painting beyond value which is being used by rich rural idiots to block the fireplace. Horrible, unhinged, feckless Martin Clay makes that decision instantaneously in Michael Frayn’s Headlong. and then dithers about it until the reader wants to cry. This is a marvellous, unusual and comic book with some weaknesses – for one, the reader will learn more than s/he need ever know about Breugels both with and without “h”s, elder and younger and the bitter relationship between the Netherlands and Spain. I admit to having ‘skimmed’ these sections – a loathsome habit – but they are rather boring to the non-art-smart reader who may be almost as confused by it all as Martin is. The other weakness of the novel is a laughable sexual infatuation and a rather farcical, disappointing ending. But, contemporary fiction seems to have to include boring learned lectury bits, gratuitous sexual obsession and endings that have run out of gas. Frayn can be forgiven these ubiquitous failings because this is a classic. Every bit as good as Sweet Dreams.

Minority Report

P agrees, but perhaps appreciated the Breugelian discourses more, although admittedly, by about page 340, grew a little weary at yet another historicist rant, albeit doubtless inserted to emphasise the narrator’s idée fixe. Headlong is a truly great comic novel, a faux-Flemish waterboarding full of hilarious pain and destruction. One more thing: some current opinion doubts that the wonderfully bizarre painting of a sea scene, with Icarus plunging headlong into the sea as almost a marginal note (see above) was done by a Breugel.

Continue Reading →The Holt Report

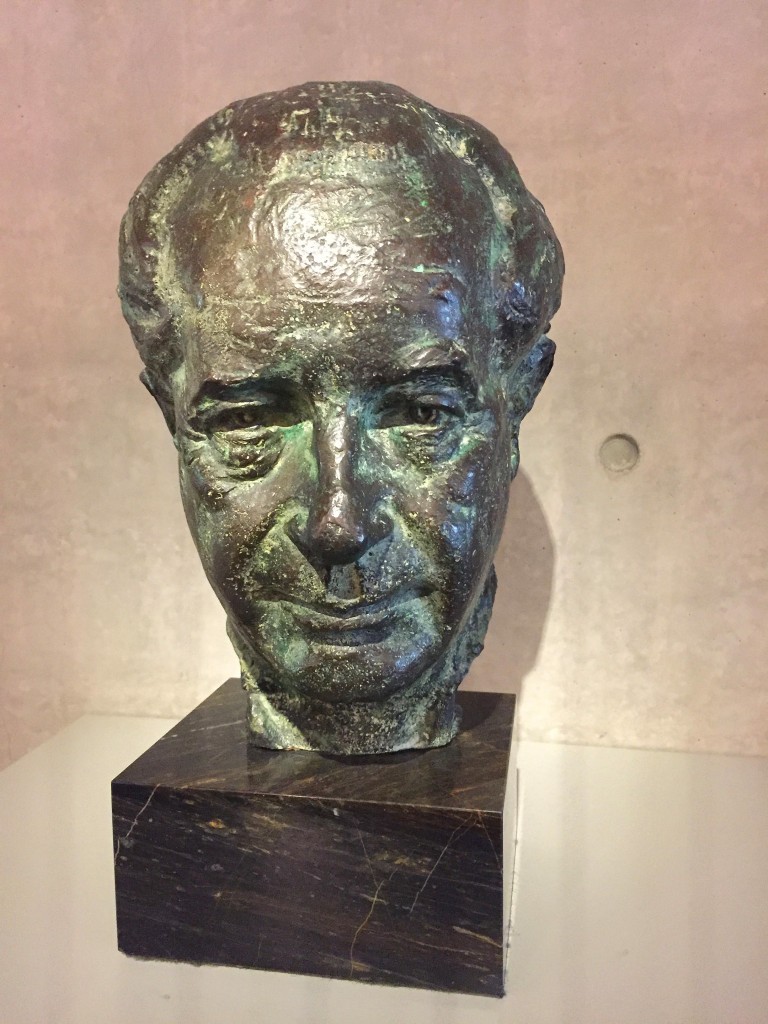

(by John Larkin and Geoffrey Barker) (1968)

Yes, Americans can joke about President Taft being eaten by wolves (particularly greedy wolves) but only in Australia could a serving Prime Minister be taken by a shark. On Sunday 17 December 1967, Prime Minister Holt went for a swim near his beach house at Cheviot, near the Heads leading from Port Phillip Bay, Victoria, into the Bass Strait, and was never seen again.

Though a shark is The Varnished Culture’s preferred theory (and after all this time, chances of finding traces are approximately nil) there are a number of other possible solutions; kelp trapping the body before sea lice demolished it; a Chinese/Russian/North Vietnamese sub; some deranged officer from the Portsea naval academy. No one knows and the disappearance continues to tantalise after almost 50 years. Mr Holt was born in 1908 so it is unlikely that he will appear, for example wandering crazed and long-haired in the Nevada Desert.

Written in taut, factual style with a refreshing lack of purple prose, this short but comprehensive account by investigative journalists from the Age covers all important aspects, including the political fallout and subsequent manoeuvring, reflecting the days of old when the Melbourne Age was a real newspaper. An important short work on a segment of history, reflecting the beginning of the end for the coalition government (1949-1972).

Continue Reading →

The Road to Character

(By David Brooks) (2015)

SBS Australia used to broadcast the Friday editions of Newshour on PBS (the American public broadcaster). That edition has a weekly political wrap-up, usually with Mark Shields and David Brooks. Whilst syndicated columnist Shields is the old-fashioned Big Democrat, Brooks takes on the aura of a Progressive Republican, less comfortable at the country club than, say, at a kaffeeklatsch.

What makes their discussions valuable in particular to us (The Varnished Culture are hardly political scientists or well versed in the ins-and-outs of American politics and policy) is the refreshing and rare civility in their discourse; their mutual willingness to actually hear and consider the other point of view, and the sense of affection for the other, even when in clear and profound disagreement. Yelling is fun on television of course, but would that we had more like Shields and Brooks!

Having got to the point of admitting we would gladly have a chat on almost any topic with Mr Brooks in a bar, we now must confess a rather lukewarm reaction to his latest book. The Road to Character walks a serpentine, contradictory, rather ambiguous road. The signposts along the way are of dubious utility – several historical exemplars are discussed but it is hard to divine any decisive threads, and this dusty track terminates at a reasonably trite dead-end.

This is especially so since ‘character’ is a rather slippery concept. Mr Brooks does not spend much time defining it, although he prefers the eternal “eulogy virtues'” to transitory “résumé virtues”. Character might be informed by actions but remains innate. Or rather endogenous. It may be changed or shaped by nurture, genes, or unusually, by force of will. Yet here is no sense of unifying theory of virtue. In point of fact, the book wallows in the confusion of post-Judeo-Christian moral relativism.

And yet there is plenty here of value, and much sound, uncommon sense. Perhaps inevitably, given the amorphous concepts with which Brooks struggles manfully, one can point to the tipping points in the eternal see-saw between subjectivism (individuality) and social cohesion (prevailing convention) and yet fail to create (as the author heroically attempts) a genuine Humility Code.

Confucius say (Analects): “Take conscientiousness and sincerity as your ruling principles, submit also your mind to right conditions, and your character will improve.”

And Jean de la Bruyère (Characters, translated by Jean Stewart), taking his cue from Aristotle that action is character, says: “No man is so perfect, so necessary to his friends, as to give them no cause to miss him less.”

Continue Reading →Death in Venice

(by Thomas Mann) (1912)

(Dir. Luchino Visconti) (1971)

Gustave von Aschenbach, an artist questing intensely after spiritual perfection, arrives, exhausted, unhappy, at the end of his tether, at the Lido and is entranced by a family staying at the same hotel, including handsome Tadzio in his little sailor suit.

Shaken by his depth of feeling, Aschenbach attempts to skip town but upon a hitch in his arrangements, he decides to return to where he was smitten, and to embrace his doom with a light heart. Mann’s novella is a polished gem, a short and sweet epitome of a bitter quest to steal innocence.

As Visconti told Bogarde: “You know it is about Mahler, Gustav Mahler? Thomas Mann told me he met him in a train coming from Venice; this poor man in the corner of the compartment, with make-up, weeping…because he had fallen in love with beauty…If you ever look upon perfect beauty, then you must die, you know that? Goethe. There is nothing else left for you to do in life.”*

There is little doubt that the older man’s feelings are a bit ‘suss’ (in fact, all of the older men in the picture, especially those given to use make-up, have serious personal issues) but thankfully both novella and film skirt the earthier aspects and concentrate on the pitiful descent of the Apollonian ideal. Visconti directs with a Wagnerian romantic splendour (the sublime opening shot is reminiscent of Rheingold), utilising pieces from Mahler’s 3rd and 5th Symphonies (Orchestra Santa Cecilia conducted by Franco Mannino), lovingly rendering Venice in its tarnished glory, its out-of-season weather, and its grip in the plague of cholera.

Central to the film is the performance of Dirk Bogarde as the obsessed, dying man: a driven composer and conductor of genius (in the novella he was a writer) who returns to embrace the fetching Angel of Death. With very little dialogue, Bogarde builds a complex persona, gives us a back-story, and embodies a moral dilemma, almost from glances alone. It vindicates Norma Desmond’s view that movie acting is primarily to be seen, rather than heard. Because his glances are so powerful and galvanising: when, for example, he decides to leave the train station and return to the Lido, smiling to himself both at the fates and the jolt of his decision, one is tempted to stand and applaud.

In fact, Bogarde’s playing is the apex of his career, a subtle triumph to cap his performances in The Servant and Accident. As Visconti said to Bogarde after filming had completed: “Your work transcends anything that I even remotely dreamed of.”*

Keats wrote, in Ode on a Grecian Urn: ‘”Beauty is truth, truth beauty,” – that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.’

[* Dirk Bogarde, Snakes and Ladders]Continue Reading →

Affliction

(Dir. Paul Schrader) (1998)

Wade Whitehouse, the local sheriff, gets increasingly out of his depth, paranoid and lethal. On a downward spiral, in full view of the whole town, he realizes that when one is “nothing any more”, there’s not much to lose. We all beware the pointless violent denouement in American films (e.g. the otherwise morbidly compelling Taxi Driver), but this bleak masterpiece contains nothing gratuitous (including its finale) and it features superb performances, particularly from Nick Nolte, Sissy Spacek, and a devastating turn by James Coburn as Wade’s monstrous Dad.

Continue Reading →The Servant

(1963) (Dir. Joseph Losey)

From a slight 1948 novella by Robin Maugham, a script worked on by Harold Pinter, and with director Joseph Losey, racked with pneumonia during a brutal winter, phoning instructions to stand-in director Dirk Bogarde (who was the only real name in the cast), this remarkable film, bleak, grim, black with snowy dashes of white, was odds-on to fail.

Tony, a delusional, well-heeled young wastrel (James Fox) has moved in to new digs and needs a manservant for…”well everything! You know.” Gentleman’s gentleman Barrett (Bogarde) fits the bill, despite a venal, visceral, almost innate hatred between him and Tony’s posh girlfriend (Wendy Craig). Why does she react so nastily towards Barrett? Perhaps because Barrett is a wicked, devious, conscienceless adventurer, and a megalomaniac? When Barrett’s “sister” (Sarah Miles) joins the household as maid, the plot thickens and decorum thins.

Tony’s decline is shown in a series of vignettes and conversations, and beautifully suggested by subtly increasing agitated and erratic behaviour. He is a weak, foolish and vulnerable man, whom friend Susan tries desperately (and vainly) to save from his servant, who is as big a slime-ball in a sea of pus one could imagine, the Cockney version of Iago or Edmund, and intent on complete domination in film’s most classic role reversal. With Barrett’s strong will, unscrupulous world-view, and access to the drugs and depravity of the demi-monde, it all spells trouble for Mister Tony.

As David Shipman commented, “The cinema since Theda Bara onwards has offered us studies of decadence, but earlier films seemed like child’s play beside The Servant.” Indeed. Satisfactory on every level, the heart of its great power is an astounding, mighty performance by Bogarde as Barrett, “Weak-strong” as he described him, loathsome and bitter, calculating and cowardly, clever and sociopathic. Bogarde in his memoir Snakes and Ladders recalled his approach to the character – after selecting the shoes, came the details: “Brylcreemed hair, flat to the head, a little scurfy round the back and in the parting, white puddingy face, damp hands…Glazed, aggrieved eyes…His walk I took from an ingratiating Welsh waiter who attended me in an hotel in Liverpool. The glazed and pouched eyes were those of a car-salesman lounging against a Buick in the Euston Road, aggrieved, antagonistic, resentful, sharp; filing his nails. [Refer to the scene of him sitting at the kitchen table after serving dinner to Tony and Susan – glaring off in the mindless distance, a large beer set before him, picking his teeth.] No make-up, ever.”

Pinter’s weltanschauung here is bleak as in Beckett, its remorseless and callous flavour extending to the minor characters. Even the mock and comical Paddy in the pub, who ruminates over his “bit of bad luck,” seems somehow unwholesome. The Varnished Culture orders you to see it (perhaps when not in a light or frivolous mood) – it is not a matter of cultural urgency, but high importance.

Continue Reading →Verdi’s Requiem

SA State Opera Chorus, Adelaide Symphony Orchestra, 26 August 2015

A very nice performance. Having a foretaste of the Requiem at the introductory session held by the Dante Society, The Varnished Culture settled back in the well worn and frayed Festival Theatre, with its ghastly art adorning the foyers (no longer ‘modern’ but eternally bad) for the full rendition of Verdi’s famous Requiem Mass. Coinciding with the staging in Adelaide of Faust, Timothy Sexton conducted the ASO, and, having rehearsed the State Opera Chorus, simultaneously conducted all 64 of them (plus kettle drum player) by alternately waving at the pit and the stage.

The Chorus was led by Teresa La Rocca (Soprano), Elizabeth Campbell (Mezzo), Diego Torre (Tenor) and Douglas McNicol (Bass), all of whom were in impressive form. The piece itself has been contentious over the last century or so – some high churchmen grumble that it is heretical; some dramatists think it narrow; some players and composers found it false (notably Hans von Bülow, although he recanted in the end).

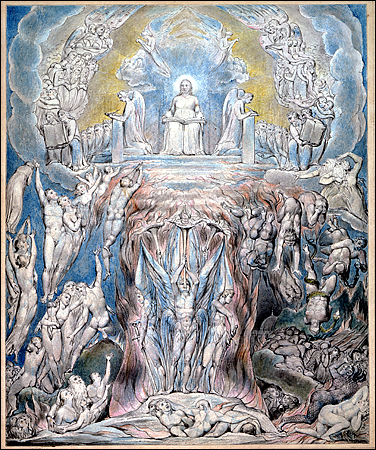

It is certainly a singular piece – neither genuinely liturgical, nor opera, but it still impresses over the course of 90 minutes of twists and turns, from Requiem and Kyrie, a restrained plea for mercy, to the thunder-filled Dies Irae, the famous explosion, akin to a Hell’s Angel riding a motorcycle into the chapel, with its repeated refrains scattered over the subsequent text, through Domine Jesu and the wind-beneath-my-wings feel of the chorus in the Sanctus, the sweet Agnus Dei and finally, the fugue Libera Me, the quiet and personal appeal for acquittal on Judgment Day, an innovation by Verdi, as it is absent from the Requiem Mass on All Soul’s Day.

P’s main reservation is the rather patchy, even loose, effect of the whole. Perhaps a Wagner may have supplied the cohesion? No matter, the individual parts are fine and if a modern audience no longer admits of fear from the reckoning (post-Rapture), the Dies Irae still compels emotion. George Martin* described the Dies Irae thus: “Verdi knocks the world apart with the violence of his music. Four cracks of doom from the orchestra, and the voices begin the dizzy slide into blackness. No one can possibly not pay attention…It is though an angry God had come down in the holocaust and, standing on the altar, was pointing a fiery finger at “you, you and you: damned’…”

* Verdi: His Music, Life and Times (1963, MacMillan & Co), page 407.

Continue Reading →