A Bigger Picture

By Malcolm Turnbull (2020)

To re-tell a recent joke, with apologies to Frankie Boyle, Turnbull’s memoir is not like Turnbull the man, in 2 respects: it has a spine, and you may not want to put it down. Yes, we’re on record as not being Malcolm fans, for whom this pretty well written and interesting book is designed, though it holds wider interest in following the August path of destiny for Australia’s 29th Prime Minister, a path strewn with garlands and fleeting triumphs, told in a voice of peerless self-confidence, well described by Jonathon Green in the Sydney Morning Herald as “first person magnificent.”

In a soft (the creators of Frontline would have called it a ‘flirt-piece’) yet revealing interview by Leigh Sales on ABC’s 7.30 programme, Mr. Turnbull kept stressing that his (legendary) ambition had a purpose…”I always wanted to get things done…to effect change, to effect reform.” Leaving aside the risible claim that change and reform were effected on his watch, this No-Power-Without-Purpose mantra sums-up Turnbull, explains his formidable personal trajectory, and demonstrates that he was never a true conservative.

As the late Roger Scruton explained, “The subjection of politics to determining purposes, however ‘good in themselves’ those purposes seem, is, on the conservative view, irrational. For it destroys the very relationship upon which government depends. This, the conservative might say, is the true source of the absurdity of communism: that it saw society entirely as a means to some future goal. Hence it was at war with the very people it had set out to govern.”*

YOUNG MALCOLM

Mr. Turnbull’s book is in 5 parts: beginnings (1954-1982), his legal and business activities and entry into politics (1983-2003), his rise to leader of the opposition and fall (2004-2013), his time as loyal (yes, that’s what he says) servant of the Abbott Government (2013-2015) and his stint as Prime Minister (15/9/2015 – 24/8/2018).

Malcolm was formed, uno ictu, such that he was never really a child. Here are some examples of his time in short pants: “We rented [in Vaucluse]…from a frightening old man called Clarrie Ball, who lived next door in Flat 1 with a snappy dog that didn’t like me…”

“The Sydney Grammar boarding house at St Ives was a brutal, badly managed place. Bullying was rife and I was particularly unpopular.”

“Next door was the classroom where he taught 1A – the brightest of the new boys, including me.”

“I loved history, often embarking on my own independent research…I probably didn’t know the word for it then, but it was the start of a lifelong interest in historiography…”

“One master was especially sleazy. When I was 14, my friend Ted Marr and I went to see Alistair Mackerras to complain about him. Alistair was an unworldly man, an innocent in many ways, and he couldn’t understand what our concern was. I told him that if he didn’t move the master out of the boarding school, I’d walk across the park to see the chairman of trustees, whom I knew to be the very grand Sir Norman Cowper, senior partner of Allen Allen & Hemsley.”

(In other words, he was a prig and a bully from early on.) He was unlucky in his parents: Coral Lansbury left for another man when he was only 10, and rarely kept in touch; she is remembered here with justifiable coldness, and may help us understand his extremely close bond to wife Lucy. His father, a gadabout and ultimately successful hotel broker, whom he adored, died in a light plane crash when the author was 28.

The co-captain and senior prefect “…left Grammar filled with confidence, ambition but above all curiosity.”

He went to Sydney U and immediately sought to be elected editor (he lost to a communist) and immersed himself in political journalism. His 1975 obituary for labor firebrand Jack Lang is somehow apt: “He was convinced of his own rectitude and regarded anyone who disagreed with him as a saboteur.” Turnbull found attractive the reportage “where the journalist is right there in the centre of the story.” He cold-called channel 9 and radio 2SM and got a parliamentary round. “Sitting in the press gallery, watching the politicians clash in the parliament below, I thought, I could do better than that.”

DABBLING

Turnbull was, along with his bête noire Tony Abbott, that quaint curio, a Rhodes Scholar, despite the former’s disdain of “imperial fantasy.” He combined his study of law with running highfalutin errands for Kerry Packer and earning on the side as a Fleet Street hack. (You certainly could not convict Turnbull of laziness). On return to Australia, shortly after rejoining the Liberal Party, he ran for pre-selection in the blue-ribbon Liberal seat of Wentworth, at the tender age of 26. He lost narrowly, not having mastered the art of branch-stacking, which he perfected in 2004. But then he had become Packer’s consigliere, advising on diverse elements of that panjandrum’s empire, including his inquisition by the Costigan Royal Commission (“…I’d resolved to see it through, believing firmly that nobody was better able to get him out of the mess than me.”)

By a combination of grunt work, threats and dirty pool, Packer was vindicated. And then another triumph: Turnbull’s victory in the over-hyped Spycatcher case, an ill-judged attempt by the British Government to stop the publication of a poor book that had pretty much washed-around the public domain already. Turnbull made more of this rather ho-hum legal victory than Nixon did of the Alger Hiss case.

RICHES

Still, he was on his way. Having staked a name and reputation for himself, and free of Packer, he formed a lucrative partnership with Nick Whitlam, and spent the next several years making a lot of serious money – which is impressive if all you want to do is make a lot of money. He writes: “Nick Whitlam became unhappy; Neville [Wran] and I never understood why.” Note that Whitlam himself riposted in the 25/4/20 ‘Weekend Australian,’ “Not true. Neville knew. Everyone in the firm knew. It was because of [Malcolm’s] unwillingness to work as a team, his unwillingness to think beyond the transaction at hand…Most left the firm when I did…[one’s] “parting shot was: “I know, Malcolm, you think that you are the smartest in the room here at Whitlam Turnbull; let me include you in a secret: you are alone in that belief.””

DITCHING THE QUEEN

That belief flowered of course, and Turnbull, disgusted with the thought that Australia could share a head of state with another country, formed in 1990 the Australian Republican Movement. He opines: “Nobody could seriously contemplate leaving the powers of a directly elected president in the undefined, and thus potentially uncertain, world of convention” which perfectly encapsulates the superior stability of a distant crowned head following convention to a partisan local one bound by a set of constrictive and myopic rules.

He quotes himself: “Australians should be able to pick up their Constitution and find in it an accurate description of how their democracy works” which must seem to most Australians a curious reason for all the ensuing fuss. The referendum was a disaster for the republicans: a damaging rift over the right model arose, and the voters clearly decided that if wasn’t broke, why fix it.

During this time he encountered leading constitutional monarchist Tony Abbott, and he quotes Abbott in referring to him as “the Gordon Gekko of Australian politics.” Turnbull deploys the Soviet tactic of painting Abbott as not only weird but mentally ill, especially when he challenged and supplanted Turnbull as Leader of the Opposition and later when Abbott was PM. Yet there is something in Abbott’s slur that seems less than crazy.

POLITICS

To paraphrase Gough Whitlam paraphrasing Tacitus, “…everyone would have agreed that he was qualified for the post of Leader if he had not held it.”

Turnbull is reasonably intelligent, diligent, and good on detail. The chapters covering his time in the 4th and 5th Howard Governments, in opposition, and as a Minister under Abbott, are patchy but interesting. A policy wonk, his overweening vanity and overconfidence undermined his efforts, demonstrating again why businessmen often flounder in the murky soup of democratic politics (Rudd referred to Parliament House as “Chateau Despair.”)

His chapters on the River Basin Plan, the GFC and the NBN are good, albeit examples of him tackling problems too big for anyone, but his early conversion to Global Warming Theory reminds us that his education favoured humanities and his core competence was finance, not physics or geology: “And I understood then, as the decade that followed confirmed, that the fires, floods and droughts were getting worse and more frequent. And we knew why. It was precisely what the scientists had foretold would be the consequences of global warming...facing the dry and fiery consequences of a warmer climate, we have a moral duty to act...” The consequences for Malcolm’s moral vanity were to be more blatant.

He seems to have been, on more than one occasion, a reluctant usurper: after he defeated Brendon Nelson in a party-room ballot for Leader of the Opposition, he made some incredible blunders. One rather curious and irrelevant one was to be fooled into using a faked email against PM Rudd (‘Utegate’), which blew-up in Turnbull’s face when the fabrication was revealed (he had no part in that, his crime being one merely of naivity). The fundamental, critical misstep arose from his failure to read the signs that his colleagues were fed-up with Rudd’s messianic schemes and the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme was the last straw.

Turnbull thought he had a moral and political obligation to support it: Joe Hockey challenged him but ran on a platform of deferring hard decisions on the CPRS, which revealed him as a political eunuch. Abbott, conceding he’d been something of a ‘weather vane’ on the issue, told Turnbull, apologetically, that he was sorry but he was going to have a go too, based on total opposition to such an idiotic scheme. (That principled conduct is not mentioned in this book).

Abbott won by a vote and eventually became Prime Minister. Turnbull endured many dark nights of the soul but was appointed by Abbott as Communications Minister, where he seems to have made the best of the mess that was the NBN, and renewed his love affair with the ABC. Possibly the most contentious parts of the book cover his shots at Abbott, including his alleged capture by Chief of Staff Peta Credlin, his charges that Abbott was a psychopath and his strangely supine response to a man he says was very dangerous, destroying the Party, and imperiling the nation. But in September 2015, he brought on a challenge – “not because I crave the limelight etc but because I know I would be a better, more contemporary, more liberal PM than he is.”

Part of the problem with these contentious portions is that Turnbull is his own source on important matters. On the Credlin issue, for example, he states that Michael Thawley, whom Abbott hired to head the Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet, was a “counterbalance to Credlin, whose influence and control he believed was excessive.” The source? Turnbull’s private diary, 14/11/2014, and we’re not told whether Thawley said as much, to whom, or if this is simply the diarist’s inference. (Actually, many of the diary entries sprinkled through the book, and the footnotes, struck us as passing strange.)

PRIME MINISTER

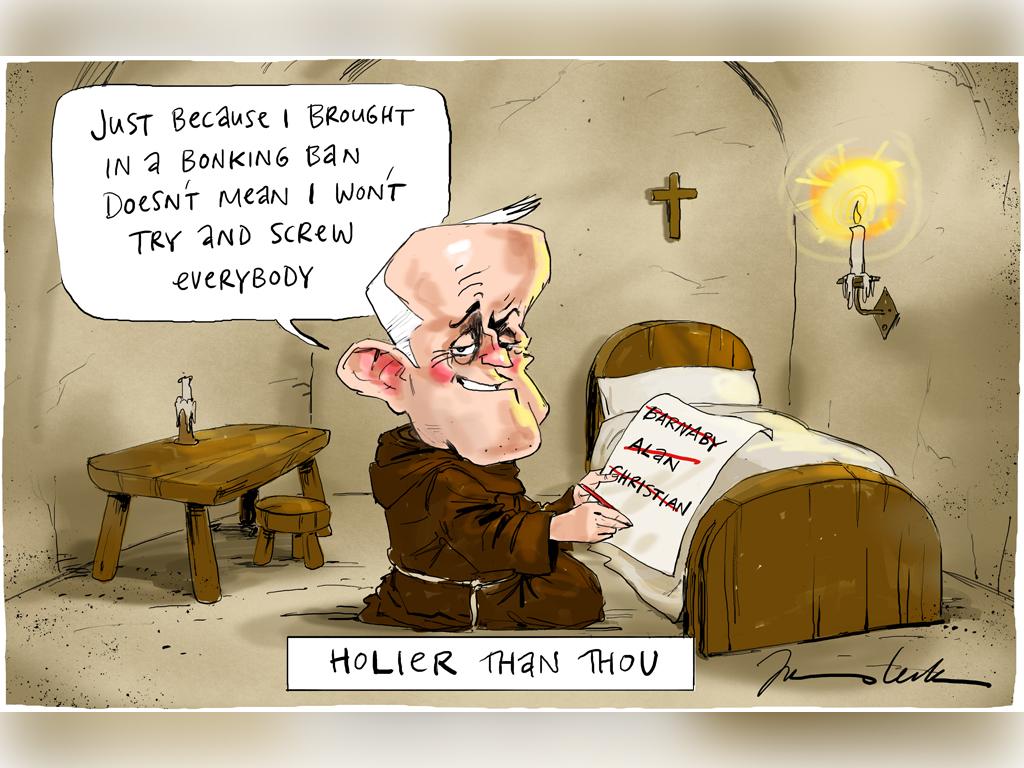

In any event, Turnbull, for all the ‘right’ reasons, masterminded an “elegant” coup against a man he calls a “besieged would-be tyrant,” perhaps forgetting that if this paints Abbott as Caligula, Turnbull is Claudius, a naive and flawed wowser whose edicts included a bonking ban and who was poisoned by his faithful servant. Before the reader shares the coup gastralgia, however, and the feverish ex post facto reasoning by which the author explains it, she has to wade through twenty or so chapters on the Turnbull government, some 350 pages of PM Turnbull’s legacy.

It is a slog, frankly. Instead of summarising it at length, we can synthesize Mr. Turnbull’s achievements thus: He (1) kept most of Abbott’s policies (including on the same-sex plebiscite, border control, national security, and the Paris CO² agreement), except for trivial flourishes such as Knights and Dames; (2) Spent like a drunken sailor on Gonski 2.0, a Julia Gillard initiative; (3) Renewed the Trans-Pacific Partnership, although without the US; and (4) Introduced a bonking ban on government ministers.

That’s about it. To be fair, although he did nothing much on tax, he had a go, and he flirted with grand schemes, à la Kevin Rudd (e.g., Snowy 2.0). But apart from hurling a lot of cash about and blowing numerous thought bubbles, there’s not much to show for almost 3 years, certainly not for the transactional over-achiever he was meant to be, one who “always wanted to get things done…to effect change, to effect reform.” This perhaps explains the disappointment of the very many who had high hopes for Turnbull. (He does get points for telling Rudd to go jump when Rudd – seriously – wanted support for a tilt at UN Secretary-General).

He does himself no favours, in the final analysis, by styling the push against him in the winter of 2018 as some sort of right-wing coup designed to bring Labour Leader Bill Shorten to the Lodge! Not only does this theory look completely deranged, and based on alleged hearsay statements that read literally mean no such thing, it also bears-out the comment of Ross Fitzgerald, reviewing the book in the 2/5/2020 ‘Spectator,’ that “it’s Abbott, rather than Turnbull, to whom the Liberal party really owes an apology.” This closing chapter of Turnbull’s is a sad coda to a fractious administration and a wasted political career.

One startling aspect of the author’s account of the coup is the failure to recognize he was dying by the sword he himself had wielded. He denounces what he refers to as the treachery, deviousness, and undermining by a “gang of right-wing thugs“, including a “foreign-owned media company'” in a mad design to blow-up Project Turnbull. He writes, apparently without irony: “Having been involved in many leadership challenges, it was all horribly familiar.” Indeed. The tactics deployed against him in August 2018 look a lot like those of September 2008 (Turnbull assassinates Nelson) and September 2015 (Turnbull assassinates Abbott).

Turnbull was Selectors’ choice for the White-anting Olympics, having eroded Brendan Nelson as party leader and Abbott as PM. Paddy Manning wrote in Born To Rule: “Turnbull pledged his loyalty to Nelson but gave him absolutely none. He simply refused to accept the decision of the party room, and the undermining began immediately.” So when Turnbull, on 21 August 2018 called a spill to demonstrate how much more loved he was than the despised Peter Dutton, who challenged, he was unpleasantly surprised to find that the vote was 48-35 in his favour, a margin so modest as to be untenable.

This increased the groundswell. Aware hostile forces in his own ranks were closing in, he released information that cast doubt on Dutton’s eligibility as an MP under s. 44 of the Constitution, and insisted that any challenge would need a public petition of at least 43 signatures of Liberal MPs. He thought that Dutton and his allies would struggle to amass that number, and he was right. But by Friday morning, he was given a petition with 43 signatures of his colleagues. His overthrow must have been awfully painful, for him and his family and friends, and he is eloquent about it. But one wonders if he felt even a stab of contrition, a soupçon of empathy, when he read that last entry on the petition? Signed by progressive Liberal Warren Entsch, the signatory added the words: “For Dr. Brendan Nelson.”

Reading A Bigger Picture, which is often interesting and informative, one is nevertheless reminded of Alexander Hamilton to Aaron Burr, who had asked “What was Washington’s most notable trait?” to which he replied: “Oh, Burr, self-love! Self-love! What else makes a god?“**

[NOTES * The Meaning of Conservatism, (2002), p. 13. And would a true conservative hang out with Vietnam protesters, Bob Carr, Jack Lang and Bill McKell, Bob Ellis, Laurie Brereton, Ray Martin, Neil Kinnock, Paul Keating, write for the Nation Review and originate the idea of the Guardian Australia? Turnbull states: “But as I reflected on the two parties, while I admired the romance and history of the Labor movement, I always felt I was a natural liberal, drawn to the entrepeneurial and enterprising.”Later he writes of admiration for Rupert Murdoch in the 1970s because he was, among other things, “politically progressive.” He does confront the smear that Turnbull approached Labor looking for a parliamentary slot and convincingly refutes it, but the fact remains that he would have been perfectly at home in the centrist wing of that party. He criticises Abbott’s government because it “lacked a coherent economic narrative” which would not be a priority, putting it mildly, for a conservative. And he quotes Jack Lang: “The Liberals have no loyalty or generosity – and no gratitude. The Labor party is at least sentimental.” (As if the latter quality was a good thing).]

————————————-

[**Burr, Gore Vidal, (1973).] [A note to the editor: This book has some repetition, some curious and unnecessary digression, and should have been cut (or, as politicians hate that word, ‘tightened’) by at least 100 pages. And we’re not sure these telling statements needed publication:“Inexplicably, we [Turnbull and Robert Maxwell] got on like a house on fire“;

“Turnbull & Partners …were more like Winston Wolf in Pulp Fiction – the people you call when you have a really bad problem“;

“I’m not a hater, as so many people in politics are“;

“Happily, Russel Pillemer and I had more to collaborate on than witness statements for the HIH Royal Commission“;

“I’ve always been pretty objective about myself, tending more towards self-criticism” and

“Peta [Credlin] has always strongly denied that she and Tony were lovers. But if they were, that would have been the most unremarkable aspect of their friendship.”]

Confucius say: Before you start on a journey of revenge, dig two graves.

[UPDATE NOTE: In the Sky Documentary by Chris Kenny, “Men in the Mirror: Rudd and Turnbull” (2 May, 2021), various insiders relate how alike these two antagonists are. Both were regarded as very bright, having great potential, yet failing in the top job. Driven, energetic egomaniacs, with lofty senses of their own superiority, they craved love and applause (both lost parents at an early, vulnerable age) and enthusiastically schmoozed the press to their advantage (and now demonize the same press having been forsaken). Which reminds one of the saying from the Old Testament, “Whoever shall be immersed in water for three minutes shall verily cease to be a c—.”]Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

0 Comments