Vietnam / Iraq

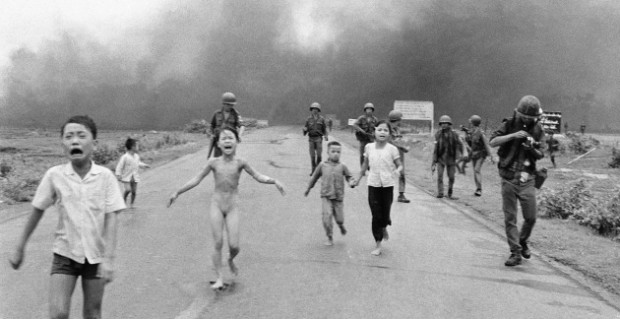

South Vietnamese forces follow after terrified children, including 9-year-old Kim Phuc, center, as they run down Route 1 near Trang Bang after an aerial napalm attack on suspected Viet Cong hiding places, June 8, 1972. A South Vietnamese plane accidentally dropped its flaming napalm on South Vietnamese troops and civilians. The terrified girl had ripped off her burning clothes while fleeing. The children from left to right are: Phan Thanh Tam, younger brother of Kim Phuc, who lost an eye, Phan Thanh Phouc, youngest brother of Kim Phuc, Kim Phuc, and Kim's cousins Ho Van Bon, and Ho Thi Ting. Behind them are soldiers of the Vietnam Army 25th Division. (AP Photo/Nick Ut)

While recently reviewing The Deer Hunter, we strayed In Country, a tangled thicket where the eternal skirmish over Vietnam carries on. Now it is held-up as a mirror to military madness, and as a parable for the incursion / invasion of Iraq. But whereas the strategic argument for Gulf War II remains opaque to this day despite inquiry after inquiry, I suggest that the escalation in Vietnam, as at 1965, is different to the events of 2003 by a substantial degree, rendering most modern comparisons between the two erroneous.

The late 1950s, 1960s and 1970s formed the middle age of the Cold War (a period that included an existential threat to the planet in 1962). In that period, Communist infiltration of nations in South-East Asia took place across the board, by insurgent agents (often hiding behind the skirts of anti-colonialism and national self-determination) and as time went by, it intensified.

In the wake of the Korean War, the Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon administrations faced the challenge of checking aggression by the communist monoliths, whilst attempting to skirt the quagmire of the local insurgencies. President Eisenhower led the creation of SEATO in 1954 (at the same time refusing to bail-out the French at Dien Bien Phu). His administration formulated the ‘Domino Theory’ so derided by later commentators (hostile to the war), and he warned his successor, Kennedy, about the simmering troubles in S.E.Asia, particularly in Laos. For his part, President Kennedy totally believed he had to hold the dominoes steady. So did President Johnson. So did Australian Prime Ministers Menzies and Holt (at some cost in blood, treasure and prestige*).

But did Kennedy’s cautious assistance to South Vietnamese President Diem give way to a full immersion under Johnson just because a Texan shoots first and asks questions later? Or as Oliver Stone would have it, the military-industrial complex so instructed him? Well, no.

The escalation came about due to factors such as:

(1) Increased North Vietnamese activity, including through the Ho Chi Minh trails in Laos;

(2) A probable attack on a US destroyer in the Gulf of Tonkin;

(3) A communist coup in Indonesia (‘the Year of Living Dangerously’), in which Sukarno also threatened Malaysia;

(4) Viet Cong trainees carrying out exercises in Thailand;

(5) Communist guerrillas operating in Burma; and

(6) The shadowy Soviet and Chi-Com patronage of the North Vietnamese forces.

In essence, South-East Asia was one of the hotter gridirons for Cold War conflict in 1964/5 and beyond.

The flouting of the 1973 peace treaty and subsequent fall of Saigon did not lead to a general collapse in the region, and this is tendered as evidence that the Domino Theory was wrong. But the South Vietnamese were overrun in 1975, not 1965. And the North was only emboldened to rat on the 1973 Treaty because Dick Nixon no longer had his finger on the button.

By drawing the line earlier on in Vietnam, bolstering regional neighbours, including via the formation of ASEAN in 1967, and increasing military and civilian support that helped crush North Vietnam’s Tet Offensive in 1968, plus the devastating bombing runs in the early 1970s, the dominoes were kept standing. Vietnam was a local tragedy necessitated by the geopolitics of the global struggle. There were sound strategic reasons to draw the line in that benighted and beautiful country. For these reasons, apart from the trite and undeniable fact that war is hell, Vietnam is not Iraq.

{*The Australian Labor Party maintained an honourable (though misguided) opposition to the War in Vietnam in the late 60s. (The Party conquered its scruples in the 1970s.) When Harold Holt said we were going “All the Way with LBJ”, Gough Whitlam observed that the trouble was, we didn’t necessarily know where LBJ was going. When John Gorton said of our role that we weren’t the Sheriff, “but part of the posse”, Whitlam retorted “Presumably this time we’ll head ’em off at the pass.”] [* UPDATE: 18/8/1966/18/8/2016: 50 years since the battle of Long Tan, our Asian Tobruk, where 19 Australians fell against an opposition of substantially greater numbers. As we write this update, the Vietnamese Government, having pulled the pin at the last moment on a planned and non-partisan commemoration at the battleground, relented and allowed the event to proceed. It would seem they remain as tough in negotiations as in Paris in the early 1970s…]

Leave a comment...

While your email address is required to post a comment, it will NOT be published.

0 Comments