The Varnished Culture's Thumbnail Reviews

Regularly added bite-sized reviews about Literature, Art, Music & Film.

Voltaire said the secret of being boring is to say everything.

We do not wish to say everything or see everything; life, though long is too short for that.

We hope you take these little syntheses in the spirit of shared enthusiasm.

All of Us Strangers (2024)

(Director Andrew Haigh)

Adam (Bill Paxton look-alike Andrew Scott) is a desolate would-be writer, living alone. After a fire alarm in his London tower block he meets Harry (Paul Mescal) who is, strangely, the only other inhabitant of the building. Harry wants to party the night away, but Adam sends him home. Soon after this, for reasons which are not clear, Adam goes to a park near his childhood home (set in the house in which director Haigh was raised) and meets his father, apparently by chance. Adam starts to spend time with his parents whom he hasn’t seen since one evening in the 1980s when he was a pre-teen. Which is unsurprising, given that they died that night. His parents (Claire Foy and Jamie Bell) are no more surprised to see Adam than he is to see them. Mum and Dad look as they did 30 years ago, although Adam is now in his forties.

Back in the near-deserted tower block, Adam does let Harry into his flat and they take their clothes off almost immediately. (In real life do all gay men jump on each other within five minutes of meeting? Or is this just on screen? Asking for a friend). Their relationship develops into something, but it’s tepid. Neither of them seems to have anything else to do and neither is particularly appealing.

After the (obligatory) ketamine-fuelled LGBTQ+ dance-club scene, Adam becomes increasingly confused, as are we. Is he drug-addled? Mentally ill?

This is a very good film. More is going on than first appears. It is ingenious, affecting and puzzling; but it could have been a great film. The ideas and the feels are undercut by the banality of Adam’s obsession with talking to his parents non-stop about how awful it was to grow up being homosexual. These speeches are preachy and out of date, particularly given that Adam’s parents seem quite okay with his sexuality. Really, if you met your long dead parents who were now somehow here and in their thirties, wouldn’t you have something to talk to them about other than how you used to cry in your bedroom because you were bullied at school? You might, for instance, ask them where they’ve been, is there a god and how they’ve kept their hair so nice after three decades in a box.

Do take note of the shirt Harry is wearing when he first knocks on Adam’s door.

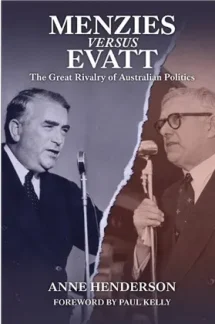

Continue Reading →Menzies versus Evatt

By Anne Henderson (2023)

Robert Menzies and Herbert Evatt were both born before Australia was – in 1894 to be exact, in the colonies of Victoria and New South Wales respectively, but they would blossom under the soon-to-be-created Federal Commonwealth. Their natural intelligence and Victorian work ethic set them on the path to success, and to some degree, Australia became the better for their struggle, in that they brilliantly represented, and advocated for, different yet necessary principles and practices of the nation’s democracy.

Menzies went to the Victorian bar, and still in short pants lead in the Engineers’ Case (1920), a seminal constitutional decision for federalism, establishing, in Sir Owen Dixon’s words, that under the Federal Constitution, “a power to legislate with respect to a given subject enables the Parliament to make laws which, upon that subject, affect the operations of the States and their agencies.” It was unclear that an award on employers in a certain industry could bind employers in a State that were government instrumentalities. Menzies, opening the batting before the High Court on a case stated, ran the line that the interveners were to be regarded as trading rather than governmental corporations. Justice Starke said this was “nonsense.” With the impetuousness of youth, Menzies replied “Sir, I quite agree.” He submitted that if he was allowed to question and challenge earlier decisions of the Court, he could put a better argument. After retiring for a time, the Court returned, adjourned the case to allow intervention by all concerned States and a full argument, with explicit leave to challenge any earlier decision of the Court. Stirring stuff. Note that Evatt appeared as junior counsel for an opposing party. Later, Menzies entered politics on the conservative side, and became Prime Minister in 1939.

Evatt was no less distinguished. After honourable service to the NSW Bar and State Government, he was appointed (by the financially and intellectually bankrupt Scullin government, but let that pass) to the High Court (aged 36!). A man who, to borrow Gore Vidal’s phrase, lived in a rarified world of theory, he was neither popular on the Court nor a ‘team player,’ and in 1940, he resigned his commission and stood for federal parliament in 1940, in the seat of Barton, winning by a handsome margin.

There had been some previous desultory exchanges between them, but from the time of Evatt’s election, the pair found themselves in the political sphere, destined to become mortal enemies. In this compelling book, the author traverses the events whereby these two brilliant, dedicated and proud men came into war with each other, creating firestorms that sucked much oxygen out of public discourse for at least twenty years. In the final analysis, Evatt, whilst perhaps the genuine genius of the pair, lost the war because he bit-off more than he could chew, he was chronically disorganised and lacked the trust to delegate, he pursued an ideology already proved as far too altruistic for humans, and his unique talent for personal relationships made adversaries of those that could have been friends. He was also, near the end, probably certifiable, surely paranoid at the very least.

Henderson concentrates on the Big Issues where battlelines were drawn. First, the election of John Curtin in 1941 (when Evatt became both Attorney-General and External Affairs Minister: a staggeringly burdensome remit – think of Mark Dreyfus and Penny Wong in the one person – or wait, forget that – bad example). Then, Evatt’s conduct of Prime Minster Chifley’s idiotic push to nationalise Australia’s banks. WWII having concluded, undeclared WWIII started, and the Cold War covered Menzies, and especially Evatt, with its umbra. In a sense, Evatt was a man out of time by 1949: his sterling but sterile work with the United Nations, where he created a path to Universal Rights deemed essential post-Hitler, was rendered otiose by the Soviet Union’s invention of Universal Misery. His last, great, and stylish act, to lead the charge to defeat Menzies’ cynical attempt to dissolve the Australian Communist Party by legislation, turned out to be a good intention leading him down to political Hell.

The Australian people tend to be suspicious of government overreach. They turfed-out Chifley’s government over bank nationalisation, a national coal strike, post-war rationing and an ambiguous approach to the iron curtain. But then Menzies arguably stepped over the line himself. He sought to banish the Australian Communist Party, by legislation, and if this failed, by Constitutional change. One suspects that, like the Abba song, he felt he would win if he lost. For though Evatt opposed the bill, Menzies was re-elected in 1951; though Menzies lost the 1951 referendum to ban the ACP, the result was to tar Evatt as ‘soft on communism,’ split the Labor Party and consign it to the wilderness for 23 years.

Let’s take some samples from Anne Henderson’s book as to these issues:

“Once in the position of prime minister a second time. lessons learned over decades saw Menzies become a careful strategist…believing in a style of delegation that left his minsters free to deal with their departments without interference. By contrast, Evatt was a chaotic manager…He expected to be central to all business.”

“While recognising Evatt’s achievements and the energy he expended in this, Hasluck found Evatt to be “emotionally simple and intellectually complex”…”

“In the heat of battle, so to speak, Menzies and his colleagues had not considered the extent of the (CPA ban) bill’s assault on, possibly, ordinary Australians…Menzies was forced to advise the House of Representatives on 9 May that among the list of 53 communist union officials he had given names for in a speech to parliament on 28 April there were five persons who were not communists.” (Reversing the onus of proof is always attractive to the persecutor, but likely to cause injustice).

When Evatt appeared before the High Court in the Bank Nationalisation case, he started off by asking two of the judges to recuse themselves because their relatives had bank shares. And though he then addressed the Court, ponderously and in his usual shrill voice, for 18 days, as David Marr observed, quoted in the book, “He was returning to the High Court which had been happy to see him go seven years before and the animosities had not subsided with time.” (The following year, 1949, Evatt bent the ear of the Privy Council for 22 days – to no effect).

Menzies told a journalist, ahead of the 1954 election: “I would leave politics this 1954 but for Dr Evatt. He’s a menace to Australia and he must be kept out of office by hook or by crook.”

Evatt’s promises to anti-communist Catholic power-broker B.A. Santamaria “…was a shopping list to die for among Movement supporters but it did not fool Santamaria who felt it rather disgusting and went home and told his wife he had met a man without a soul.”

Labor was tipped to win the 1954 election but Menzies, it was claimed, pulled ‘2 rabbits out of the hat’: first, he hosted the newly crowned Elizabeth in February and March 1954. And then, there was the Petrov affair. Vladimir Petrov, Consul at the Soviet Embassy in Canberra, had defected and Menzies took the opportunity, while Evatt was out of town, to announce an espionage Royal Commission: two classic ‘wedges”, even though it seems Menzies may not have planned it so neatly. Henderson writes: “…after three days of strongly supporting the government’s stand on Petrov and the commission…Evatt launched an attack on Menzies…which accused the PM of “sly insinuations” and “making a crude attempt” to disparage the previous administration’s Security service handling.” The economy had picked up and that played to the Liberal’s strength. But it would be hard to discount the effect of the photo, prominently published, of a distraught Mrs. Petrov (one shoe missing), being hustled to a plane at Mascot airport by Soviet goons.

Evatt made things much worse in the wake of the Petrov affair. When the Royal Commission gathered speed, it was revealed that several of his staff had been involved in Soviet shenanigans. And then Evatt decided, in August 1954, to appear before the Commission as counsel. He should have kept a 1,000 miles away. His splenetic, paranoid and bizarre performance was seen as evidence that he was having a nervous breakdown, “shouting his conviction that the documents in the case [were] concoctions.” The Commission removed him as an advocate. Henderson cites Ligertwood J stating: “I have read all the documents, the Moscow letters and any other relevant material and, I repeat, every one shows how fantastic is the allegation that they were forged for the purpose of injuring the Labor Party of Australia.” “The other justices immediately concurred.” Then Evatt ‘doubled-down’ and spoke at length in the Parliament, again ventilating his conspiracy theory. Menzies played him on the break, replying mildly (but lethally) that the House had just witnessed a “very uncommon privilege…[to having] heard counsel who has unsuccessfully advanced certain arguments before a tribunal have the opportunity to advance them for a second time before a tribunal which has not heard the witnesses and has not read the detailed evidence…That is something I cannot remember in my fairly long experience of public affairs.”

Then Evatt, seeking evidence relevant papers had been fabricated, wrote in 1955 to what he thought an impeccable source as to their dubious provenance: Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov. Enough said.

It would have been an appropriate ‘Beria Moment’ for the Labor Party to have had Evatt metaphorically executed, especially when he called for the expulsion of a subversive element – Victorian Catholics, treacherous anti-communists or ‘traitors’ as he called them. A dumb, fascistic move, revealing an authoritarian streak that had previously broken from cover only occasionally. Henderson speculates on whether Deputy Arthur Calwell could have calmed matters, or knocked Evatt off. Fred Daly, that classic insider, was scornful of Calwell: “pathetic…hesitant, uncertain and waiting for Evatt’s job”. The Victorian branch of the party was purged, a fatal schism was created, which in the author’s view, was brought about because Evatt was at base, “an intense secularist,” anti-Catholic more than anti-communist, a naive internationalist who forgot, or never learned, that politics is above all local.

After more election defeats, where the party still could not bring itself to defenestrate its “brilliant boy,” Evatt was offered a slot as Chief Justice of the NSW Supreme Court by State Labor, whereupon he left the political stage in 1960. But Menzies, perhaps remembering his undertaking to keep Evatt out of power ‘by hook or by crook,’ may not have relaxed his vigil totally until Evatt died in November 1965. Menzies retired as PM in January 1966.

Continue Reading →The Zone of Interest

(Directed by Jonathan Glazer, based on the book by Martin Amis) (2023)

Poland is one beautiful country; with a plethora of mountains, verdant meadows, sea-coast, and more lakes than most. Which explains why so many imperialists wanted their grubby hands on it. In 1939, for example, as a result of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, Poland was neatly sliced into two zones. One zone, the Russian one, executed an unknown number of Poles, sometimes with organisation, at other times in a haphazard panic. The German zone, where Poles (and others) were dealt with under typical Teutonic efficiency, is the ‘Zone of Interest’ in this film. That’s where Auschwitz was built, a complex of over 40 concentration and extermination camps which, over the period 1940 to early 1945, killed well over two million people.

Cue Jonathan Glazer (Under the Skin) and his take on Martin Amis’ 2014 novel, that channels Hannah Arendt, Schindler’s List, and all the rest. Many folks will think a film riffing on the well-worn trope of ‘banality of evil’ to be silly, or, worse, boring. For this reviewer, it is neither: rather, a riveting, edge-of-the-seat, domestic thriller, with amazing sounds, surreal touches (a phosphorescent Polish girl secretes apples behind the slave-worker shovels at night) and a dash of Wannsee Conference pathology. But it fails nevertheless, as all Shoah films must, for reasons we will attempt to explain.

The film’s intent is clear, and on its own terms, works well enough. Rudolf and Hedwig Höss (Christian Friedel and Sandra Hüller) and their five winsome children are living the dream in an idyllic country manor, with attentive servants, food on fine china, abundance and a lovely large walled garden, including a massive greenhouse. The film opens on a picnic by the river, a walk through the woods, home in two splendid motor cars, and then packing the children off to sleep. But, hang on…peeping above that garden wall next morning is what looks like a death camp – and here’s Rudolf in uniform, riding though the camp gate – to carry out his basically administrative tasks (logistics of rubbish disposal cycles, energy supply, fertilizing the greenery, the selection of work force (including the Joy Division), chastising staff for picking the flowers in an unruly manner, having supply-trains met, etc.)

At Casa Höss, hand-me-down clothes, a fine fur coat and jewellry, and teeth, are wheeled in from next door. ‘Cars’ keep ‘backfiring’ in the distance, preceded by yelling and barking. Rudolf and eldest son go horse-riding, commenting on the fauna while men in striped pyjamas are marched through the sward. Some agreeable fishing and swimming is disrupted by unidentified river impurities. Hedwig’s mother (Imogen Kogge), from modest circumstances (she lost her bid for a deportee’s curtains) marvels at how well things are with her daughter, until she sees what goes on at night over the bad-neighbour fence (about the only peep we get, until the film’s end).

After Mother leaves her breakfast, and a note the next morning, Hedwig lashes out at one of her Polish servants, observing tartly that she could have her husband scatter her ashes. The juxtaposition, of interior scenes of quiet and occasionally noisy domestic life, with the heavy-hints of genocide next door, will pall with many while it will resonate with many.

After some bureaucratic shuffling, Rudolf is to return home to assume charge of the final solution as it goes into even higher gear. From a palace reception in Hungary, imminent target for deportations, he ambles among the guests in a distant manner, oddly reminiscent of the finale to The Leopard, has a desultory conversation with his wife, and then prepares to leave to assume his important new role, attacked by nausea as he descends the dark stairs. And that is about it. Interspersed throughout are some blank, coloured screens, dread musical tweaks that combine yawps, groans and burps from hell, and enough static, often silent, set pieces to fill an Ingmar Bergman festival.

It is difficult to know what to make of this. Certainly the film is watchable; certainly it is not for all tastes. The acting and production are first class. But what does it achieve, exactly, since it poses as much more than art or entertainment? The discretion in not showing us directly how the Final Solution is playing out, yet the continual coy hints at it, begin to look like a hollow cabaret-turn. The madness of crowds is a phenomenon that continues to baffle the best minds and give succour to the worst souls. As we see, the view of fellow humans as filth, or rodents, goes on and on, and is probably endogenous, such that peace for all time becomes unimaginable. But how do you film that?

We can do no better than quote Clive James, in a slightly different context, here: “As with Stalin’s Great Terror, only a madman could guess what was on the way. Even the perpetrators had to go one step at a time, completing each step before they realised that the next one was possible. The German Jews were the most assimilated in Europe. They were vital to Germany’s culture – which, indeed, has never recovered from their extinction…The whole Nazi reality was a caricature. The more precisely you evoke it, the less probable it looks…There is no hope that the boundless horror of Nazi Germany can be transmitted entire to the generations that will succeed us. There is a limit to what we can absorb of other people’s experience. There is also a limit to how guilty we should feel about being unable to remember…Santayana…said that those who forget the past are condemned to relive it. Those who remember are condemned to relive it too. Besides, freedoms are not guaranteed by historians and philosophers, but by a broad consent among common people about what constitutes decent behaviour. Decency means nothing if it is not vulgarised. Nor can the truth be passed on without being simplified. The most we can hope for is that it shall not be travestied.“*

[*”The Observer”, 10/9/1978, reviewing Holocaust.] Continue Reading →One Day (Netflix 2024 British television series.)

If you can be bothered starting this listless series, we recommend that you binge watch all 14 (!) episodes because once you switch off, you’ll never bother going back.

To start with, the plot is suspense-free. Rich golden rich boy Dexter meets socialist Emma (a girl from the wrong side of the tracks and of another race) at a posh university. They go their separate ways until..! Whatever could happen?!

Even this hackneyed story could be worth watching – Leo Woodall (previously seen in White lotus 2) is terrific as the languid upper-class Dexter – although he could do with some concealer around the eyes. He is desperately and steadfastly in love with feisty Emma (Ambika Mod) for reasons best known to bad casting agents. Mod has a perpetually miserable long sad face. She barely smiles for the first twelve (!) episodes. Dex becomes a tv presenter. Emma becomes a socially aware teacher (of course). They remain best friends, which is difficult to accept, given that Emma meets everything that Dexter says or does with a contemptuous sneer and insults – he’s a privileged hedonist, his tv career is a measure of how shallow he is, he is not politically aware.

When he takes her to a swish restaurant and demonstrates a development of sophisticated tastes, Emma throws a public tantie. When the selfish, cruel, boring and smug Emma calls him these names (and others) the audience wonders why he bothers with her at all. Leo’s Dex is vulnerable, unanchored and has the patience of a saint. Emma is a nasty, self-obsessed sad sack.

After some years of taunting and deriding Dex, Emma decides that she might as well give him a go. It’s not clear why, because, after all, it’s not like she has to settle – she is also inexplicably irresistible to all men – not just poor Dexter,

The support actors are very good and do what they can with the standard roles of faithless spouse, jealous spouse, aristocratic parent and supportive friend. Add the clichés of the genre – unhappy separate marriages, humiliation at a baronial pile, a friend’s hilarious wedding, Paris, a surprise return to the turgid plot – stir with a misery stick and you’ve got One Day. The last episode is, admittedly, quite affecting but that is entirely due to Leo Woodall and it is not worth the long journey.

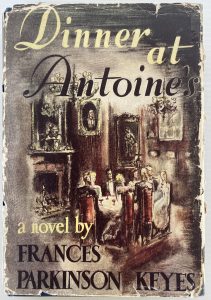

Continue Reading →Dinner at Antoine’s (Frances Parkinson Keyes)

(1949).

“Keyes” rhymes with “skies” not “keys”. Being privy to arcane pronunciations is the sort of marker which separates those who are in New Orleans Society from those who are not. Only the former know that the sidewalk in 1940’s-50’s New Orleans is called the “banquette”. Only the former are admitted to Antoine’s Restaurant on St Louis Street without a long wait on the banquette, if at all. Orson Foxworth is certainly one of the former and, on a warm afternoon, is immediately lead into the special lunch room when he entertains his niece and several intimate friends.

The layout and history of the restaurant are expanded upon in great detail, as are Foxworth’s equally ridiculously named guests – Leonce St Amant, Caresse LaLande, Sabin Duplessis. Foxworth’s guests are beautiful and fabulously dressed. Meet Amelie – a youthful and soigne widow. “Her corn-coloured hair lay in great coils above the soft ringlets which framed her radiant face. Her big blue eyes snapped and sparkled. Her delicately rouged lips parted over tiny white teeth. Her svelte figure triumphed over the exacting cut of her dress“. Keyes never met an adjective or adverb she didn’t want to work to death, sometimes to unintended effect. “Snapping eyes” and “tiny teeth”? Don’t feed Amelie after midnight. Foxworth’s Washington niece, Ruth Avery, “attractive and intelligent and well poised and pleasant and dependable and sincere” is the only one with the name and hair (natural chestnut curls) of a real human. Ruth is visiting her suave Louisianan uncle in louche New Orleans and looking to get hitched.

Nor are we spared descriptions of the the food at Antoine’s – presumably on the real menu of the real restaurant in the immediate post-war period. It sounds revolting. Take huitres Foch, “So he spread toast with pate de fois gras, and heaped fried Louisiana oysters on top of that, and poured Madeira sauce over the whole thing“. If you don’t like the sound of that, you can have “glistening, ruby-coloured” globules of shrimp in aspic.*

The clothes of past beauties are given a similar close study, including annual pageant winners from 1900. The present belles are described too. We already know that Clarinda has dreamy eyes, a slow, charming smile, slow grace, tapering white fingers and exquisite oval nails. Now we see her…. “evidently on the point of starting to a large afternoon party, for she was dressed as if for some festive occasion. Emerald green plumes swept gracefully across her glossy hair from the crown of her small sable hat; her close-fitting jacket and full, ankle-length skirt were make of emerald green velvet, sable trimmed, and she was carrying a large sable muff. Framed as she was by the white columns, she might have stepped straight from a canvas by Goya; yet this exquisite picture seemed to have been mysteriously modernised by the hand of some still greater master.” The sort of great master who imagines Sherwood Forest/Gone with the Wind themed afternoon parties.

The mansions are equally lovely and outdated. “The regalia which Odile had worn as Queen of the Pacifi completely filled a glass-walled cabinet and several similar cabinets were crowded with Dresden china, Dutch silver, snuff boxes, and other miscellaneous bric-a-brac. A series of antique fans, encased in frames which followed their shape, and a set of bisque figurines, representing amorous shepherds and coy shepherdesses, added to the general effect of artificiality and uselessness.”

The staff and servants do not have beautiful visages, figures or minds. They are not quite human. “The maid’s prompt appearance suggested that she might have been lurking nearby hoping for just such a summons. At all events, when she entered her expression was one of eager anticipation. And this became even more marked as she rolled her large velvety eyes from one pile of clothing to another. ‘You may have all the things on the bed, Lop,’ Caresse told her. ‘That is, you may take them away and divide them with Ona. Mind you don’t try to play any tricks though. I’ll check with Ona later and find out whether you’ve been fair.’ ‘Ain’t gwine play no tricks, Miss Caresse. Ah don tol’ Ona already you was a-fixin’ to give us some of yo’ pretty clo’es. Us’n mightly proud to git ’em, Ah kin tell you.’ Lop reached over the bed and swept the clothing that lay there into her covetous arms….She laid down the others and bent to pick up the straying garments, gasping with incredulous delight.”

An international merger and a murder mystery scaffold all of this. A pistol appears in the first act. There’s a faithless husband, a saintly doctor, a missing note, a purloined key, a fake alibi, a roving reporter, shadows on a blind, inscrutable foreigners and long discussions about opportunity and motive. These shenanigans do not convince. Nor does the rather odd incident in which a lifelong playboy bachelor suddenly ditches the chaste object of his many years of adoration when she says the wrong thing; spurns her utterly, and almost immediately thereafter, falls instantly in love with the perfect (much younger) woman who has admired him from afar and is only in the book for that plot point.

So, this book and its characters are vapid, generally pretty, overrated and rather amusing. We feel that at times Keyes is as contemptuous of her characters as she is adoring. She knows that they are all rather silly and tasteless. If you like that kind of society, now and then, then this will amuse you.

[* Sounds like the kind of Louisianan fare described by A.J. Liebling – ed.]

Ezekiel 25:17. “The path of the righteous man is beset on all sides by the inequities of the selfish and the tyranny of evil men.”

A Poor Thing Indeed

Poor Things (Directed by “Yorgos” Lanthimos – 2023)

What do Lanthimos’ “Poor Things” and M. Night Shamalayan’s “The Village” films have in common? They are the latter works of erstwhile promising directors. Lanthimos’s “The Lobster” is fabulous. As is the rightfully feted Night Shamalayan’s “The Sixth Sense”. Original, surprising and engaging works. After that, Shamalayan made the hold-your nose “The Village.” Lanthimos took a step down to the so-so “Killing of a Sacred Deer” and then nosedived. “Poor Things” is twaddle. Sadly, it looks like it’s all over for these two.

“Poor Things” has beguiled critics with its steampunk, big-sleeved art direction. But that’s all there is. The task of the aesthetic is to distract the poor viewer from the tired plot, the thin characters and heavy-handed message. Dr. Godwin “God” Baxter (Willem Dafoe) is a mad scientist of the old kind. (Yes, like Frankenstein, yawn). He creates “Bella”, a monstrous meld of an adult suicide and the brain of her baby. Bella lurches about à la Elsa Lanchester and refers to herself in the third person. There’s no sense to the rate at which, or how, she develops. We are enjoined to see the uninhibited toddler in a woman’s body, which seems counterproductive, given this film’s alleged “feminist” purpose.

Bella wants to be independent, so she goes off with seedy adventurer Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffulo). Ruffulo is too old and soft-centred for this role. Dashing and irresistible he is not. Bella enjoys her independence – being locked in a chest, abducted, dancing like a maniac, working in a brothel – all the great feminist desires. She has already decided that when the fun is over she will go home and marry weedy needy Max (Ramy Youssef). As all good feminists do.

By the time Bella gets home, the viewer is sick and tired of seeing Emma Stone in every kind of see-through outfit, writhing away joylessly. Hitched to a sadist who caused her inner adult to suicide, she escapes and takes over God’s conceit of playing Dr. Moreau.

Stone does well enough with the clumsy script. The viewer cannot, however, say how Willem Dafoe performed because his entire performance is a mass of gruesome facial scar makeup and stomach tubes. Like Bella herself, “Poor Things” is a ghastly, humourless hybrid, with no sense of timing and no soul.

Continue Reading →Maestro

(Directed by Bradley Cooper – Netflix, 2023)

Maestro is not a biopic of Leonard Bernstein, a popular and influential conductor, composer and musicologist. We do follow his career, but high and low points are marked by whirls of scenic grabs and musical snatches. The film’s focus is on Bernstein’s long and bumpy marriage to Felicia Montealegre, going from breathless first-flush intimacy, to star couple, to cold understanding, to a final tenderness. Whilst this renders the film a little thin, putting it mildly, it succeeds upon its chosen horizon.

This is due to great turns by Bradley Cooper and, in particular, Carey Mulligan, as the happy/unhappy/tolerating couple (who converse at His Girl Friday speed and with Robert Altman-style clarity). At their fashionable apartment during Thanksgiving, she tells him “you’re going to die a lonely old queen” if he is not more careful (and discreet). This prediction turns out to be true, emphasised at the moment of that prediction by the passing of Macy’s giant Snoopy balloon. There are many soirées that convey an empty Truman Capote feel, although we may have missed the famous ‘radical chic’ party as the scenes hurtled past.

Music being more talked-about than heard throughout, the longest performance piece is Bernstein’s famous conducting of Mahler’s Resurrection Symphony in Cambridgeshire, where Lenny and Felicia resurrect their relationship to an extent. Bernstein was very much a ‘hands on’ emotional conductor, and this part of the gnostic discipline comes out, but we learn nothing. However, the film is well worth watching, even if it cannot teach us.

Continue Reading →Dream Scenario

(Directed by Kristoffer Borgli, 2023)

“The general function of dreams is to try to restore our psychological balance by producing dream material that re-establishes, in a subtle way, the total psychic equilibrium.” (Carl G. Jung, “Approaching the Unconscious.”)

“Humani nihil a me alienum puto” (“nothing human is alien to me”) – Terence.

If the ‘ Viennese quack’ (according to Nabokov) Sigmund Freud is correct, all dream content is disguised wish-fulfillment. So mind what you wish. In Dream Scenario, Professor Paul Matthews (a sublime Nicolas Cage) is a balding, middle-aged academic, the type Dirk Bogarde used to play – bright, ineffectual, wistful, querulous – who is neither published (well, he’d have to write something), nor quoted (unless plagiarized) nor noticed. His wife (Julianne Nicholson) cares for him in a condescending fashion, and his daughters and his biology students find him uncool, harmless and unmemorable.

Then comes the event sociological: Matthews starts turning up in people’s dreams. Even people who have never seen or heard of him. Initially, within vividly-filmed sequences of ‘elusive dreams of private persons to which we hold no key’, he’s just there in the background, a self-conscious extra: walking by a bad car accident; raking leaves, ambling by while a girl seeks to avoid alligators by climbing on a piano; loitering during an earthquake at the college; inspecting mushrooms while a man is hunted by a blood-drenched assailant. He’s thrilled to find himself famous, and seeks to exploit this fame to get his swarm-theory book (not yet written) published. But the social-media-savvy talent agents (Michael Cera, Kate Berlant, Dylan Gelula) want him to become the face of that tempestuous refreshment, Sprite, and in the case of Gelula, to re-create an erotic dream, which turns out rather badly in real life.

The dreams start turning quite dark, in a way that sees Matthews go from curio to outcast, in an amusing and provocative reflection on the transience of fame, superficial and fragile social mores, and cancel culture, reminiscent of the recent Black Mirror episode, “Joan is Awful.” But then, like a discarded meme or an over-extended twitter-fight, the film runs out of puff, focus, and ideas, and folds like a cheap suit. The Professor (unlike ‘Frank Underwood’ (aka Kevin Spacey, another negation victim) from House of Cards) spurns an offer to be interviewed by conservative pundit Tucker Carlson; meant as a hip, woke, smirking, cultural reference, it was in fact a big ‘miss’ – The Prof. should have appeared with Carlson; it would have resurrected the character, and beguiled us in a way that the film’s conclusion did not.

Continue Reading →The Ring in Brisbane

(Lyric Theatre, Queensland Performing Arts Centre, Second Cycle: 8, 10, 12, 14 December 2023)

Like Wagner’s monumental work, the first ever staging of The Ring in Brisbane grew in the telling. It was commissioned in 2017, and advertised in early 2019, with bookings in a ‘shuffle format’ scheduled from 13 June of that year, for performances in November/December 2020. Then a Sino/American research project let a bat loose from Hell, and gross inconvenience, and death, ensued. The Ring was set aside, although not as long as Wagner did while he fretted, and tinkered, and researched. With a revised cast, it was finally staged up-north in December 2023. Touted as the first ‘digital’ version of the production (cf. Ulrich Melchinger, Kassel 1970-74; Harry Kupfer, Bayreuth 1988/1992), we’ll have a bit to say about that below.

But the 2nd Cycle was, overall, a triumph. [TVC has a few quibbles, stated below, but really, who cares?] Early mail insinuated that the Queensland Symphony Orchestra had been a tad scratchy in round 1; however, by the time cycle 2 came around, conductor Phillipe Auguin, a Ring veteran, had knocked all into shape. (I think Donner’s hammer was out of synch with the orchestra, and Siegfried’s hunting horn missed a beat once in Götterdämmerung, but these don’t even count as quibbles.) White-haired, smiling, and seemingly avuncular, Auguin, we understand, is selector’s choice in a long line of disagreeable Conductors (e.g., Toscanini, Solti, Fritz Reiner, and in the land of make-believe, Tár). But he and his musicians get kudos for a magnificent performance over 4 long evenings.

Das Rheingold opened the batting, and was fine, although one’s first encounter with Chen Shi-Zheng’s design felt like having chugged one too many martinis. Some of the staging was annoying. Alberich as a toad was woefully inadequate. The piling-up of gold to “hide” Freia was another visual fail. At the conclusion, the ascent to Valhalla, the rainbow bridge through the mist was represented by a long, luminous spike piercing the roily heavens, akin the end of the old Dr. Who programme. No problem with that, but moving side panels blundered into view, containing a digital decorative meld of colours and shapes straight out of William Morris, Leon Bakst and the Saville studio. Wotan’s and Fricka’s introduction was straight out of The Mikado.

The cast were wonderful, particularly Warwick Fyfe as Alberich (though his costume made him look like a cross between Gregor Samsa and Grizzly Adams). Deborah Humble as Fricka, and Hubert Francis, as Loge, were also stand-outs. We thought Daniel Sumegi was strangely muted as Wotan, but he roared back in Die Walküre. The lithe Rhinemaidens skipped and slid down the props with élan.

There was a closing, irritating, thigh-slapping dance number that added approximately nil, a superfluous trope appropriated from some Maoist wet-dream opera such as “Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy,” or “The Red Detachment of Women.”

Die Walküre

Perhaps the most crucial chapter in the saga was very forcefully played and sung: Lise Lindstrom has grown since her Brünnhilde in 2016 and here she was sublime, matched by Sumegi’s Wotan, their urgent discourse under a digital backdrop of circles and cobwebs, which we thought appropriate. Humble as Fricka was superb, as were Anna-Louise Cole and Rosario La Spina as Sieglinde and Siegmund. (I spoke to one of the musicians afterwards, who described playing Walküre as “fun.” We wouldn’t have put it like that, but 10/10 for enthusiasm.)

Once again, some grumbles about staging are apt. On the whole, minimalism (à la Wieland Wagner) reigned, thankfully. We didn’t understand the speedboat chassis on which characters respectively lounged and then dragged, or the table in Hunding’s hut which bastardised Brancusi, Henry Moore and the worst of modern plastic art. But the dragon of fire encircling the sleeping Brünnhilde was terrific, evoking memories of Elke Neidhardt’s Adelaide Ring.

Siegfried

The night belongs to Siegfried and Stefan Vinke, who continues to grow in the role, along with Lindstrom’s Brünnhilde. Sumegi, now the ‘Wanderer’, his bête noire Alberich (Fyfe), Andreas Conrad as Mime, Andrea Silvestrelli as the voice of Fafner, and Celeste Lazarenko as the athletic Woodbird (actually, her stand-in), are very good. Liane Keegan sings at low volume, which suits the portent of Erda’s warnings, undermined as they are somewhat by her strange garb, making her seem like the fifth Banana Split. And there are more dancers, twirling their infernal ribbons, which might have put the orchestra a bit out of time.

Götterdämmerung

This is the closest Wagner gets to the Nibelungenlied, and it is a most satisfying closing-of-the-circle, well done by all, in particular the real hero of the whole saga, Brünnhilde. Once again, we worried that either she or Siegfried would fall off the rock – it looked over 15 feet high, with no guard rails. Also, while it was pushed into position by the camouflaged minions, it creaked quite noisily (WD-40, anyone?). We did, however, like the Wizard of Oz-like door under which Alberich gets into a sleepy Hagen’s head, and the hunting ground, a wintry array of Patagonian mountains and a moon that went from Melancholia to Lord of the Rings.

The director had decamped after Cycle 1, we heard, having urged his players to declaim impassively (!) – We suspect this bit of directorial chauvinism was disregarded by the players once the director left, given the work represents one of the loftiest heights of romanticism, and is a pre-Freudian masterpiece, fortunately played as such. But if our mail is accurate, it does explain something of the sterility of aspects of the operas in this production. Chen has been reported as saying “Opera as a performance, as theatre, isn’t my cup of tea.” However, the production did spurn the wan flatulence of Regietheater.

In any case, and notwithstanding the truly idiosyncratic staging of the world’s final immolation – Brünnhilde and a Mechano warhorse around and atop a pile of generic supermarket tins, doused in bleach, while a truly crazy bunch of CGO swirled about – could not defeat the simply gorgeous music, song, and emotion as we all ‘saw the world end.’ Andrea Silvestrelli, highly effective earlier as Fafner and Hunding, was, as a sonorous and vigorous Hagen, outstanding in a crowded field of sheer brilliance. The audience gave a long standing ovation that was neither phony nor excessive.

Digital Effects

The digital effects were generally impressive (hundreds of LED screens, video material and sensors in the ensembles), although often they were too busy, distracting, or intruded for reasons unclear to this correspondent at least (“Effects without causes”?). The technology will enable future productions to be more portable and economical, but as tended to be the case in this production, the risk is the temptation to explore the medium at the expense of clarity and concision. The drizzled titles at the start of each opera included Chinese characters (we surmised, translations), which were neither ‘provocative’ nor ‘insightful.’ But the visuals were often beautiful: for example, the falling golden leaves in Die Walküre, which owed much to digital effects; and the funeral procession to the Trauermarsch in Götterdämmerung, which did not. It was brave to try it and it has, quibbles notwithstanding, succeeded.

The Ring remains one of the peaks of western art, a necessary rampart, still, against the barbarians and their scrobbling retinues.

A Thank-you to the Richard Wagner Society in Queensland

At the splendid Tattersalls club in Brisbane on the afternoon of 9/12/23, RWSQ gave one of a series of receptions to celebrate the Ring in its fair city. Wagnerians had come from far and wide. The President of the Society, Rosemary Cater-Smith, was regrettably indisposed; Professor Colin Mackerras AO gave the welcome and introduced the Society’s new patron, Heldentenor Bradley Daley, who belted out Siegfried’s song whilst he forges Nothung. Being within a few paces of Bradley, the force of his voice was particularly powerful.

(Incidentally, TVC, as usual, funded attendance at the Brisbane Ring out of its own shallow pocket.)

Continue Reading →Back to Otto’s

(Southbank, Brisbane, December 2023)

We were last at Otto in 2021 – and had a wonderful lunch. Dinner this time, and just as good, actually even better. It was prefaced by a 90-odd minute power cut at our hotel (and the Queensland Premier hadn’t even formally stepped down yet) but after we were able to return to our room and freshen up, it was a short walk along the Brisbane river to this lovely restaurant.

Service was impeccable; tables were not too close but not overly distant either. We were under cover but over the water’s edge, making us feel both daring and comfy.

L had Paccheri ai Frutti di Mare, long tube pasta with Moreton Bay bug, squid, blue swimmer crab, confit tomato, garlic, chilli and basil. Despite the abundance of ingredients, it was light and finely balanced. P plumped for Anatra, duck breast sliced into bite-sized chunks, with rich cherries, roasted baby onions and almonds – lovely. By the time we’d helped that down with a Le Battistelle Montesi Soave Classico, the only room for dessert was a glass of champagne.

Otto is a perfect special occasion restaurant.

Continue Reading →