The Varnished Culture's Thumbnail Reviews

Regularly added bite-sized reviews about Literature, Art, Music & Film.

Voltaire said the secret of being boring is to say everything.

We do not wish to say everything or see everything; life, though long is too short for that.

We hope you take these little syntheses in the spirit of shared enthusiasm.

The Undoing

(Netflix – 6 parts) (2020)

We know that bad things are about to happen when a miniseries begins with an attractive couple (Nicole Kidman and Hugh Grant as Grace and Jonathon Fraser) engaging in happy banter and in-jokes with their child (Noah Jupe as Henry Fraser) over a busy breakfast. Their New York apartment is Bohemian and chic, their clothes are Bohemian and chic, Jonathon is a paediatric oncologist, Grace is a marriage therapist for sleek couples and Henry goes to a ludicrously expensive private school which values diversity. You can see the trouble brewing from here, can’t you?

HBO is usually better than this. Grace Fraser is without doubt the world’s dumbest psychiatrist (although she is oddly referred to as a psychologist during a criminal trial). No half-wit who had spent their life alone in a remote cave could miss the mental issues by which someone close to her is beset, and which are displayed with carpet-chewing fervour in the final scene.

The acting is fine, although Noah Jupe is miscast as Henry, he’s too old for his role and, being a hobbit-type, could never be the biological child of Grant and Kidman. Donald Sutherland appears periodically as a sort of Chorus, expressing his loathing for Jonathon (“He’s like me!”). Matilda de Angelis is also miscast, putting in an odd turn as a plump, miserable, irritating femme fatale; looming at every turn. Her appeal is a mystery.

Someone is not where they are supposed to be, someone else is where they are not supposed to be, a third person gets their face bashed in and everyone is a suspect – no surprises there in this sort of by-the-numbers ‘psychological thriller’ (or should that be ‘psychiatric thriller’).

If you do watch this (perhaps for the lovely grey-blue faded beauty of Upper East New York, the John Carpenter-like music or Grace Fraser’s fitted bodice, full skirt brocade coats) skip the tedious opening titles. A red-haired girl wafts about, playing with bubbles while Nicole warbles, “Dweam a Little Dweam of Me”. It goes on for hours.

There’s a trial – of course. It’s risible. The defence lawyer (who seems to run a murder trial on her own) is more of an investigator and New-Age counsellor than an attorney. At one point, remarking that the case against her client is “circumstantial” (in reality there is no case), she says, “we need to offer-up another suspect”. It’s more like a popularity contest powered by Facebook than a trial. [Noma Dumezweni’s performance as the attorney is smart money to win an Emmy, which tells you all you need to know about the Emmys – Ed.]

The revelation at the end was unexpected but that’s because it defies all the laws of physics, chemistry, psychiatry and screenwriting.

Love You Long Time: The Earl of Louisiana

“The Earl of Louisiana” by A. J. Liebling (1961)

Liebling’s witty and nostalgic book shows us something of the old time politics and how it seems fresher and more vibrant than the sterile and shrill shenanigans of today. True, he had to travel to Louisiana (where the citizenry don’t expect corruption, they demand it) and he had a ringside seat to the Long legacy (the famous ‘Kingfish,’ Huey Long, Governor from 1928 to 1932 and a U.S. Senator until his death by gunfire in 1935, had been followed by younger brother Earl, Governor from 1939 to 1940, 1948 to 1952, and 1956 to 1960). Under the law then, a Governor was not eligible to serve consecutive terms: Earl thus decided he’d resign a few months before the end of his term and then campaign to ‘succeed’ his newly installed replacement – something of which even wily older brother Huey hadn’t thought.

From left: Huey, Lucille and Earl Long

Trigger Warning

The Longs were long on populist re-distribution and pork-barreling but they were also anti-racist in a State still prone to segregationist law and policies. Indeed, to effectively ameliorate such pre-Civil Rights Act injustices, it was necessary for an anti-racist to pose as a racist (he handed out quarters to white kids, nickels to black kids). As Earl snarled on the floor of the Legislature – as Liebling notes, being Governor, he probably had no right to speak as the head of the Executive – “you got to recognize that niggers is human beings!” This against a bill to remove black votes from electoral rolls. One lawyer observed to Liebling: “the state was tight as a drum and crooked as a corkscrew; now it’s still crooked, but it’s open to everybody.”

Long was a good ol’ boy but one on the side of the angels, fighting against segregationists, vested interests like Standard Oil, The Times-Picayune newspaper that detested him, and sundry other forces of darkness, but he fought with all the weapons he could amass. His stump speaking was legendary, a discursive, cornpone, meandering blend of invective, confession, pledges and appeals to the Supreme Deity. Of a hostile publisher; “Mr. Luce is like a man that owns a shoestore and buys all the shoes to fit himself. Then he expects other people to buy them.” When he promised to a representative of the cinema cartel to remove a tax on movie tickets, then renegued, his promisee said of his clients, “What do I tell them now?” to which Earl replied, “I’ll tell you what to tell them. Tell them I lied.” What ultimately blindsided him in the summer of 1959, however, when his impassioned speech brought him to the brink of apoplexy, was that his wife, Miz Blanche, would have him committed to a mental hospital in Texas. He did not see that coming.

With typical southern flair, Earl talked his way back to town, sacked the health officials that had facilitated his premature demise, and set his re-election strategy in motion. He fell short in the end, but the ride is wild and Liebling, the urbane staff writer for The New Yorker who fell (a little) under the demagogue’s spell, documents it with wit, affection and coolly measured prose:

“A Louisiana politician can’t afford to let his animosities carry him away, and still less his principles, although there is seldom difficulty in that department.” “Extended on a pallet in a dusty little hotel at Covington, where he lay after winning his way to freedom by firing the hospital officials, he recalled old newsreel shots of Mahatma Gandhi.” “The next sequence was pastoral – on the veranda of Earl’s old-fashioned farm at Winnfield, in his home parish, where it is politically inadvisable to paint the house too often.” “His delivery is based on increasing volume, like the noise of an approaching subway train; when he reaches his climaxes, you feel almost irresistibly impelled to throw yourself flat between the rails and let the cars pass over you.” “Square-chinned and leathery, Roussel has the kind of head Norman peasants carve on wooden stoppers for Calvados bottles.” “Outside, Alick [Alexandria, in the central part of the State] lay prostrate under the summer climate of Louisiana, like a bull pup flattened by a cow.” “The row of glowing cigar ends swaying in unison reminded me of the Tiller Girls in a glow-worm number.” “‘Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do!’ [quoth Earl on the stump in Alexandria] At this point he was interrupted by wild handclapping from a group of elderly ladies wearing print dresses, white gloves, straw hats and Spaceman eyeglasses, who had been seated quietly on the platform…They were under the impression that it was an original line.”

Uncle Earl on the stump

Throughout, Liebling salts his articles (that became this book) with local colour and great set-pieces: Earl’s weird and wondrous shopping trips (he bought in bulk when he spotted a bargain – potatoes, goldfish, alarm clocks, billy goats, pitchforks, country hams, beer, etc); His daily review of form guides and telephoned bets on the gee-gees; Liebling’s visit to gubernatorial candidate Mayor deLesseps Morrison at City Hall in New Orleans (looking over all the autographed photos of the Mayor with various notables, Liebling wrote “I found the entire display an engaging disclaimer of false modesty“); Dining at the Governor’s mansion where one of his servants performs political cabaret turns to general hilarity; ““Vigorous” is another word that Morrison uses too often. It has connotations of hard labor that displeases voters in a warm climate“; In Glasgow covering the UK general election of 1959, dis-spirited by the bland, beige bromides of Macmillan and Gaitskell, he writes: “Nostalgic, I read a quotation from Uncle Earl: ”Jimmie Davis loves money like a hog loves slop.””

In the end, the run-off left standing only Mayor Morrison and Jimmie H. Davis, the eventual winner. Davis, the man who famously wrote “You Are My Sunshine” as well as less wholesome ballads, spelled bad news for the State’s less wealthy African Americans. As the writers of An American Melodrama wrote, “It seems odd that such a sunny fellow is also a relentless segregationist and was the author of the heartless legislation that took Negro women with illegitimate children off the relief rolls and left them to hustle or starve.” Meanwhile, Uncle Earl ran for State Congress, and won, but he died before taking up the office.

And Liebling, the irrepressible gourmand, liked Louisiana cuisine as much as P. J. O’ Rourke did the fried food in Arkansas when he went south to investigate the Clintons and Whitewater. Big, lengthy meals are a staple among politicos – think of the endless rounds of bars, cafes and restaurants inhabited by the crew in The Circus. Liebling was a big boy who liked his food (he liked three dozen oysters as a starter); in the introduction to the 2008 edition of the book by Jonathan Yardley, he reminds us that “in The Earl of Louisiana [Liebling] … recounts stupendous, and to the reader stupefying, repasts in the restaurants of New Orleans – with the result that he became dangerously obese.”

Some examples of this: “Manale’s…provided a glorious lunch of pompanos studded with busters-fat soft-shell crabs shorn of their limbs, which are to the buster-fancier as trifling as a mustache on the plat du jour must seem to a cannibal.” “A PoBoy at Mumfrey’s in New Orleans is a portable banquet. In the South proper, it is a crippling blow to the intestine.” “It was a good dinner, built around mallards shot by one of the guests, who emptied his deep freeze in the name of hospitality.” “The trenchers went around, great platters of country ham and fried steak, in the hands of black serving men, and sable damsels toted the grits and gravy.” “…we sat down to dinner in New Orleans – three dozen apiece at Felix’s and then shrimp and crabmeat Arnaud and red-snapper en court bouillon…” “In Kolb’s they serve planked redfish steak, snapping-turtle fricassee, jambalaya and gumbo, as well as pig’s knuckles and wursts…”

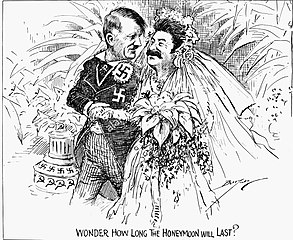

The Belt and Road to Serfdom

(“The Road to Serfdom” by Friedrich Hayek) (1944) [and why it matters now]

“While the last resort of a competitive economy is the bailiff, the ultimate sanction of a planned economy is the hangman.”#

The Argument

In 1933, the year Hitler came to power in Germany, there was a view that the fascists’ National Socialism model (as the joke went, neither nationalist nor socialist) constituted the lees of the empty vessel of capitalism, and that socialism and centrally planned economies represented the vibrant new vintage for the future. That year, Hayek, a Newby at the London School of Economics, wrote a short memo demolishing such nostrums, noting that “the scare of Russian communism has driven the German people unawares into something which differs from communism in little but name.” Nazism, then, was just another form (albeit more vivid in its moral squalor) of socialistic command-and-control as the Soviet system, “not a reaction against the socialist trends of the preceding period but a necessary outcome of those tendencies...the fusion of radical and conservative [Prussian] socialism.” Eleven years later, contemplating the end of the worst global conflict of our times, Hayek expanded such ideas in this book, a landmark and decisive refutation of socialism.

Essentially, Hayek demonstrated, socialism calls for central planning – government control over prices, incomes, property, resources, enterprise and endeavour; rejection of the free market and its ‘chaotic’ setting of prices, incomes, property, resources, enterprise and endeavour. He proved by historical example and clear logic that socialism, even implemented with the purest and most altruistic intent, could only be meaningful through coercion – totalitarianism, tyranny, despotism, and oppression in the name of liberation. He quotes Alexis de Tocqueville on the authoritarian nature of socialism (1848): “Democracy attaches all possible value to each man; socialism makes each man a mere agent, a mere number. Democracy and socialism have nothing in common but one word: equality. But notice the difference: while democracy seeks equality in liberty, socialism seeks equality in restraint and servitude.”

In other words, socialism renders individuals as no longer free to choose how to live their lives but mere automata in a ‘rational,’ ‘scientific’ clockwork of serfdom or slavery where a small cabal of enlightened overlords formulate and administer (but never explain or articulate) how things be done. The obvious idiocy of such a paradise in practical terms needs to be explained in times of darkness and confusion – 1933, or 1944, or 1945, now, and perhaps always. The argument against pre-emptive collectivism via state control and its invariable descent into economic stagnation or collapse, has never been defeated, but it yet may be, through apathy, ignorance, obfuscation and misplaced good intentions. This book is more a political and sociological document than a purely economic one, but underpinned by clear understanding of the dismal science.

Of course, we currently contend with the spectre “democratic socialism, the great utopia of the last few generations, [which] is not only unachievable, but that to strive for it produces something so utterly different that few of those who now wish it would be prepared to accept the consequences…” Some of us, indifferent to wealth, suffused with ‘altruism’, or lazily preferring freedom from choice, have an unwholesome affection for the specious ease of leaving all to central planning, abdicating their right of choice along with their responsibility for chosen risk. It all seems so easy, but no longer couched as central planning but “investments” in “wage justice,” and to solve the ”environmental crisis” or the ”war on poverty.” Incredibly, Marxism and Socialism, like Frankenstein’s Monster, seem to be galvanised and rise again.

The absurdity and bitter fruits of central planning (not in any general policy sense, but in the genuinely socialistic sense of direct control) can be seen by a review of the economies of (1) Soviet Russia [Remember the kolkhoz described in John Barron’s classic KGB: it “contained one ramshackle store to sell bread, vodka, canned goods, and sundries, but its shelves were mostly empty. Years before, Moscow planners had allotted the store a piano and two motorcycles. They were still there, unsold and encrusted with the dried spittle of contemptuous people who could neither afford nor use them“]*; (2) Mao’s China [“the country was reorganized into “people’s communes” pooling possessions, food, and labor. Peasants were conscripted in quasi-military brigades for massive public works projects, mostly improvised…Mao’s steel targets had been implemented so literally as to encourage the melting down of useful implements as scrap to fulfill the quotas…From 1959 to 1962, China experienced one of the worst famines in human history, leading to the deaths of over twenty million people“]** and (3) Cuba [“An INRA (National Institute for Agrarian Reform) delegate, accompanied by a couple of armed soldiers, usually appears at a farm and announces that INRA is taking over everything but a certain portion. He may return later and cut the former owner’s allotment in half. Though the law says nothing about farm machinery or cattle, they are also appropriated. The whole transaction is completely informal; there are no hearings, no inventories, no receipts.”]^

Hayek wore no rose-coloured glasses about capitalism. He could see clearly enough the excesses that could arise through monopolistic practices (albeit these are often a first step towards socialism: vide the socialistic tendencies of contemporary giant monopolies such as Facebook, Amazon, Google et al), narrow vested interests, selfishness and materialism, the bruises from competition and the like. But he also saw clearly that there was no other way than to accept the myriad spontaneous forces of society, with appropriate safeguards to allow individuals equality of opportunity but not of outcome (“To produce the same result for different people, it is necessary to treat them differently“), through fair competition not arbitrary direction. Capitalism did not emanate from a textbook: pursuit of happiness, division of labour and free exchange are organic and so is the market – and while the market can be a moron, it is the only sure way to establish prices and incomes (Australia should abolish the Fair Work Commission, and its ideas of a “just wage,” and try it). As opposed to “the impetus of the movement toward totalitarianism [that] comes mainly from the two great vested interests: organized capital and organized labor.”

As Hayek points out, “…because all the details of the changes constantly affecting the conditions of demand and supply of the different commodities can never be fully known, or quickly enough be collected and disseminated, by any one center, what is required is some apparatus of registration which automatically records all the relevant effects of individual actions and whose indications are at the same time the resultant of, and the guide for , all the individual decisions. This is precisely what the price system does under competition, and which no other system even promises to accomplish.” And one synthesis that enhanced these natural processes was money, “one of the greatest instruments of freedom ever invented by man“, which gave serf and slave alike the chance to get on a footing with their masters.

These freedoms require a rejection of the false cul-de-sacs of ‘market’ or ‘competitive’ ‘socialism’ that some who ought to know better try to propound as a “fair” (favourite weasel word of the left Intelligentsia), third or middle way. “Either both the choice and the risk rest with the individual or he is relieved of both.” Ultimately, Hayek plumped for individual liberty, and with the end of WWII in sight, he feared that the world would commit the error of maintaining peacetime governance on a war footing, tilting the balance in favour of planned and dictatorial crisis-management against freedom. Whilst he had a coat of hard mittel – European varnish, Hayek was, at heart, a 19th century liberal – as Orwell described Charles Dickens, “a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls.”

Serfdom Crossroad – Now

“When the government has to decide how many pigs are to be raised or how many buses are to run, which coal mines are to operate, or at what prices shoes are to be sold, these decisions cannot be deduced from formal principles or settled for long periods in advance. They depend inevitably on the circumstances of the moment…In the end, somebody’s views will have to decide whose interests are more important; and these views must become part of the law of the land, a new distinction of rank which the coercive apparatus of government imposes upon the people.”

Whilst this can be pasted ready-to-wear on China under the modern CCP, you could attach parts to parts of western social democracies with relative ease. (Hayek notes a 1939 estimate that “the upper 11 or 12 per cent of the Soviet population now receives approximately 50 per cent of the national income.”)

“The conviction grows that if efficient planning is to be done, the direction must be “taken out of politics” and placed in the hands of experts – permanent officials or independent autonomous bodies.”

You couldn’t get a pithier statement that can be directly applied to the response of various democracies to the Covid-19 pandemic. In Australia, parliaments virtually shut down. The Prime Minister formed an ad hoc body

styled as a ‘National Cabinet’ to implement policy but the various State governments were more-or-less free to do as they chose within their sovereign borders. This they did, and a policy of plague management

transmogrified – without articulation, explanation or consultation – into an eradication policy: eradication of individual liberties on an hysterical, disproportionate and unprecedented scale. On this aspect, Hayek warned that “some of the men who during the war have tasted the powers of coercive control…will find it difficult to reconcile themselves with the humbler roles they will then have to play.” One might substitute “plague” for “war” and apply that alert to the State Premiers of Victoria, Queensland and Western Australia; in fact, in varying degrees, to the other States and Commonwealth Government as well. As does this: “What are the fixed poles now which are regarded as sacrosanct…? They are no longer the liberty of the individual, his freedom of movement, and scarcely that of speech. They are the protected standards of this or that group, their ”right” to exclude others from providing their fellowmen with what they need. Discrimination between members and nonmembers of closed groups, not to speak of nationals of different countries, is accepted more and more as a matter of course; injustices inflicted on individuals by government action in the interest of a group are disregarded with an indifference hardly distinguishable from callousness; and the grossest violations of the most elementary rights of the individual, such as are involved in the compulsory transfer of populations, are more and more often countenanced even by supposed liberals.”

In this plague year of 2020, we saw Australians banned from returning to their own country; banned from leaving it; banned from crossing state lines, in apparent/arguable breach of section 92 of the Constitution; locked in their homes unless adjudged by a bureaucrat as ‘essential workers’; arrested on beaches, golf courses, parks (and in the case of one pregnant woman in Victoria, handcuffed at home in her pajamas for suggesting the State government was overreaching); denied necessary and in some cases life-sustaining medical treatment; forced to close businesses; forced from hospital beds into Aged Care Homes to die; quarantined, hectored, lectured, and harassed, all often to the accompaniment of confused, contradictory and opaque edicts based on the highly spurious guesses of so-called experts.

“Others, it is true, believe that real success [in addressing unemployment] can be expected only from the skillful timing of public works undertaken on a very large scale…remuneration would soon cease to have any relation to actual usefulness.”

Prime Minister Rudd’s $14 billion primary school building program that failed to meet construction deadlines, was inflexible, often superfluous and had inadequate yet unnecessarily onerous reporting requirements*^ comes to mind.

“A movement whose main promise is the relief from responsibility cannot but be antimoral in its effect, however lofty the ideals to which it owes its birth.”

Because socialism obsesses over ends rather than means, with its only moral base being the sacrifice of the individual for the ultimate good of the whole – a conundrum that effectively puts its hierarchy at war with its underlings, and requires the state to smite the individual who dares to differ – its totalitarian imperative will tend toward and provide “special opportunities for the ruthless and unscrupulous.” (Hayek cites the famous dictum of Lord Acton; “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.”) One need look no further than Top People in various socialist regimes, with an affinity for central planning, to gauge their human worth: Hitler, Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, Castro, Enver Hoxha, Robert Mugabe, Hugo Chávez, Kim Jong-un… As a concomitant to rule by scoundrels, the truth must, inevitably, be suppressed, or even more effectively, transformed. So language, the outer clothing of ideas, is stripped of colour and design and replaced with a dead grey uniform devoid of nuance (e.g. ‘social justice’, that ‘empty phrase with no determinable content‘), brilliantly identified in Hayek’s chapter, “The End of Truth” and of course even more brilliantly in Orwell’s Nineteen-Eighty-Four.

In a chapter, “The Totalitarians in our Midst,” Hayek cites the English communist historian, E. H. Carr: “The victors lost the peace, and Soviet Russia and Germany won it, because the former continued to preach, and in part to apply, the once valid, but now disruptive ideals of the rights of nations and laissez faire capitalism, whereas the latter, consciously or unconsciously borne forward on the tide of the twentieth century, were striving to build up the world in larger units under centralized planning and control.”

This was a crypto-syndicalist analysis of Europe after Versailles: to see such views in our contemporary society, take out “Soviet Russia,” “Germany” and “twentieth”, insert in lieu “Democratic Socialists”, “People’s Republics” and “twenty-first” and you have the corporate view of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation and its Sinophile running dogs. On this, Hayek is also apt: “The Left intelligentsia, indeed, have so long worshipped foreign gods that they seem to have become almost incapable of seeing any good in the characteristic…institutions and traditions. That the moral values on which most of them pride themselves are largely the product of the institutions they are out to destroy, these socialists cannot, of course, admit.” But as with Dutschke’s and Gramsci’s Long March Through the Institutions, the flabby and flaccid guardians of western freedom and thought have dropped their guard, and allowed a creeping collectivism and diminution in cultural value to mug, tranquilize and convert Western Civilisation into an irrational confusion, a project that continues apace. As Milton Friedman said in his 1971 introduction to The Road to Serfdom, “we preach individualism and competitive capitalism, and practice socialism.”

Winnie-the-Pooh and the Bleak Prospects of International Order

While not central to his thesis, Hayek in 1944 could not ignore the world’s conflagration or the challenge of reconstruction that lay ahead. At that stage, the future of Europe was in hazard, and the Allies had a knotty problem: one of theirs was not one of them. The period 1945 to 1990 thus became an existential threat between the old liberal nations with their open markets and individual liberties, and the Communist Monolith with its attendant strengths and weaknesses. The so-called ‘end of history’ with the fall of the Communist bloc in Eastern Europe was merely a presage of new struggles and power-shifts: the religious nihilism of the Islamic schism and its debris turned-out to be a sideshow to a much greater threat to individual liberty: the rising imperialism of Communist China, particularly under Xi Jinping from 2012.

Whilst the United States remained the world’s leader after 1990 in terms of military capacity and economic might, there has been, within the same period as the ascension of Xi, a sense of American decline, notable for the timid foreign policy of President Obama, the aggressive ‘America-First’ pivot of President Trump and the uncertain footing of the imminent administration of President-elect Biden. As to the latter, Mr. Biden’s age and possible debt to the left-wing of his party, make it difficult to predict with much certainty how the increasingly bellicose CCP will be addressed. For example, while at Kyoto, and Paris, and beyond, China continues (with help from its international socialist functionaries) to be styled a ‘developing country’ and increase carbon emissions, there are those in the U.S. Democratic Party – now in control of the White House, Congress, and perhaps after 5 January 2021, the Senate (and thus the Supreme Court) – who propose socialism for America, in the forms of policies such as the Green New Deal (Wage fixing and job guarantees, public housing and free education, 100% renewable energy with an energy guarantee to all citizens, junking the fossil fuel industries, ‘weatherizing’ all public buildings and infrastructure, or by construction anew, to achieve maximal energy efficiency, water efficiency, safety, affordability, comfort, and durability, including through electrification, fully subsidising transportation systems in the United States to eliminate pollution and greenhouse gas emissions, spurring massive growth in clean manufacturing in the United States and removing pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from manufacturing and industry as much as is technologically feasible, working collaboratively with farmers and ranchers in the United States to eliminate pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from the agricultural sector as much as is technologically feasible, and forcing recalcitrant countries to ratify and legislate zero-emissions targets. It sounds a bit like Moses the raven’s Sugarcandy Mountain from Animal Farm).

In the meantime, Europe is in flux in the wake of the recent Brexit deal. Whilst one can understand and even sympathise with Britain’s decision to leave, it will tend to weaken both the UK (riven by guilt and anti-colonialism, which will now have its own constituent countries, such as Scotland, agitate to leave) and Europe, which struggles with the economic fetter of a single currency spread over a disparate polity. International Authorities – the United Nations, the WHO, the IMF – have fallen foolishly in love with socialistic ideas, abandoned the defence of Western Civilisation formed since the Renaissance and enlightened capitalism, lost their power or even inclination for ‘distributive justice,’ and are now yoked or owned by China after succumbing to Robert Conquest‘s Second Law of Politics: Any organization not explicitly right-wing sooner or later becomes left-wing. Which makes Hayek’s statement so prescient: “...while the great powers will be unwilling to submit to any superior authority, they will be able to use those “international” authorities to impose their will on the smaller nations within the area in which they exercise hegemony.”

Which is what the CCP is doing. Sheer bald-faced lies about the provenance of Covid-19; boycotts, intolerable tariffs and sanctions against nations calling for an international investigation into the pandemic’s origins; the ‘annexation’ and subjugation of Hong Kong; their ‘Company Store’ debt-trap diplomacy under the auspices of ‘collaborative’ belt-and-road programmes; the oppression of Tibet and religious and ethnic minorities; the lack of a rule of law; the suppression of a free press, free speech, freedom of movement and other individual rights; the sabre-rattling in the South China Sea and elsewhere; the patronage of terrorist states; the industrial espionage and cyber-war; the racial-supremacy and imperial arrogance; the nauseating disregard for human (and animal) rights. Cato the Elder, before the Third Punic War, admonished that Carthago delenda est (“Carthage must be destroyed”). Rather than adopt the warlike mantra ‘CCP delenda est‘, it might be more constructive to re-visit Hayek’s great book, and take up the defence of the principle there espoused, when the world – at least, our current age – “takes it for granted and neither realizes whence the danger threatens nor has the courage to emancipate itself from the doctrines which endanger it.”

How Xi sees the world

Unhinged

(Directed by Derrick Borte) (2020) (Netflix)

The portentous opening credits, and indeed the horrendous opening sequence, suggest that Unhinged is going to have something profound to say about contemporary wrath, taking its Road Rage homily as a linchpin: sort of a cross between Duel, Falling Down and Romper Stomper. Alas, instead we get a trashy, c-grade, repulsively violent serving of haute psychomania.

“You ain’t heard of a ‘courtesy tap’?”

Russell Crowe (an un-named man in a pickup truck) is at the end of his tether. Understandably distracted, he dawdles at an intersection with the lights on green. This causes annoying and scatty single mum Rachel (Caren Pistorius), who is already having a bad day (what with her messy divorce, her no-hoper, sponging brother and his girlfriend camped at her house not paying board, her doddery mum, and having just been sacked by a client for oversleeping, and now stuck in traffic taking junior Kyle – Gabriel Bateman – to school) to stand on her car horn – instead of applying a quick toot, or “courtesy tap” – and overtaking the pickup in an aggressive fashion.

‘The Man’ sidles up to her car and asks, fairly reasonably, for an apology. Not getting one, he decides to teach Rachel “what a bad day is...” From these promising beginnings comes a preternatural series of ingenious and ultra-violent episodes that play-out (despite often leaping broadly beyond the bounds of logic) with predictable tedium. In fact, somewhere along the feverishly developing twists and turns, viewing the ridiculous behavior of Rachel (she’s initially feckless and stupid but then finds miraculous inner resources), one found oneself wishing a little violence on her.

Crowe is very good, as usual (he was in Romper Stomper which also featured extraordinary in-your-face violence, but apposite in that film), and everyone else is fine, particularly the hapless lawyer friend (Jimmi Simpson) who cops excessive feedback, Stephen Louis Grush as the hapless fellow who tries to render assistance at the gas station, who also cops excessive feedback, and Anne Leighton as the annoyed client, who is lucky to avoid excessive feedback). The car chases, car crashes, and other instances of graphic brutality are vivid and galvanising, but the violence is ultimately ludicrous, the characters are undeveloped, the script is inadequate, and the finale is straight out of a bad dream of Quentin Tarantino’s.

Continue Reading →Right Ho, Jeeves

(Written by P.G. Wodehouse) (1934)

Your correspondent has a terrible confession to make. The unburdening of this shocking secret, whilst cathartic, may very well lead to a global un-platforming.

No, I haven’t been selling or buying on the Dark Web; I’m not a secret member of Antifa or Neo Nazis; I didn’t cast 134,000 votes for Joe Biden just before dawn the day after the U.S. election. It is much worse: I recently read “Right Ho, Jeeves” and didn’t find it funny at all. It’s about as funny as a child molester, actually.

Which is not to say it isn’t a light, pleasant read. Idle rich dolt Bertie Wooster wishes that his valet, Jeeves, would jolly well stop interfering with Bertie’s attempts to match-make, in two cases: of his old pal Gussie Fink-Nottle with soppy Madeline Bassett, and alumnus Tuppy Glossop with Bertie’s cousin Angela. Why someone asexual as Wooster would be any good at it is unexplained, but he certainly isn’t.

Hilarity ensues as Wooster works his magic wand, with unfortunate results. But the impassive, implacable Jeeves comes to his idiot Master’s rescue and all’s well that ends well.

Wodehouse has a nice line in the type of upper-class tweeting one expects from an upper class twit in the 1920s, and there are some amusing set pieces – Fink-Nottle’s drunken speech to the boys of Market Snodsbury Grammar School, Tuppy’s attempts to thrash Bertie when he thinks the latter has designs on Angela, and the exasperation of Bertie’s Aunt Dahlia are good examples, but frankly, this sort of stuff dates cruelly. Furthermore, one suspects that it appeals in particular to the type of clubbable English chap who schooled at Winchester, Stowe or Dulwich College. Elites in England love Bertie Wooster, without recognising him in themselves. And the sort of uncomplaining, attentive, discrete competence that Jeeves possesses went out with the days of indentured servitude, decent public education and heroic mercantilism.

“So what’s wrong with a white mess jacket?”

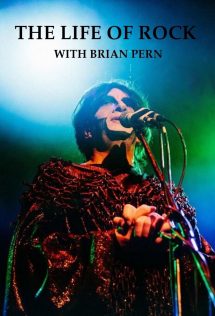

Brian Pern: A Life in Rock

BBC TV (2014 – 2016)

These 3 series, following, in semi-documentary style, the musical wanderings of Stowe-educated prog rock mystic and pain-in-the-neck Brian Pern, is one of the most hilarious things on TV, a worthy descendant of This is Spinal Tap, only better because it is not so loosely based on Peter Gabriel.

The [Genesis/Thotch] pastoral schoolboy silliness of the early seventies gives way to the Great schism of 1977, allowing Brian Pern to pursue both solo career and role of secular saint and activist, where his insane lack of sense of linear time drives record producers, his former band, his manager, family, his documentary filmmaker, Martin Freeman, and a myriad others, up the wall.

Simon Day (whom you will probably remember from the sketch/pastiche “Fast Show” – think Carl Hooper from “That’s Amazing”, the annoying fellow in the pub who “helps” with the pinball and quiz machines, vaudevillian Tommy Cockles, Dave Angel – Eco Warrior, John Actor, the chap who thinks every girl in the office is coming on to him; many more) is just great as Pern, with his naive, childlike, over-earnest, entitled and megalomaniacal take on the world – he’s even got Gabriel’s slow sludgy voice down pat, at its most sublime when explaining, on some piece to camera, his latest dopey scheme such as recording apes or staging a live concert on top of Mount Kilimanjaro. In a rich and rollicking cast, we shout out to the remaining members of erstwhile prog band “Thotch” who are a treat: Paul Whitehouse as the peevish Pat Quid, Nigel Havers as a randy keyboard player, 2 others whose names no-one recalls – as are Michael Kitchen as the put-upon and derisive manager, Lucy Montgomery as the bizarre Pepita (and others), Jane Asher as ex-wife Cindy Pern, Adam and Shelley Longworth as estranged children Tallow and Ripple (shades of the Osbournes? but for heaven’s sake don’t let them near a recording studio) and Simon Callow as crazed ex-Thotch member Bennet St John, now reduced to appearing as Henry VIII at a roast beef and ale restaurant, still dreaming of a comeback. There’s even a nice turn by Roger Moore, sending up Richard Burton’s work on War of the Worlds.

It is convenient (thanks to Wikipedia), to summarize the 3 series thus:

Series 1

1 ‘Birth of Rock” – we are introduced to Thotch frontman Brian Pern as he takes a look at how the genre of rock music was born.

2 “Middle Age of Rock” – Brian takes a look at protest songs and charity singles including his own, “Succulent Chinese Meal”, the most famous charity single of all time, “Doctor in Distress”, and the most obscure charity songs like “Snooker Loopy” by Chas & Dave, which isn’t a charity single at all. Brian also looks back at 1985’s Live Aid concert and reveals how Russia tried, but failed, to put an end to the so-called “Global Jukebox” by almost killing Phil Collins as he travelled to the US leg of the concert via Concorde.

3 “Death of Rock” – Brian looks at how aging rock bands reform after not performing for many years.

Series 2

1 “Jukebox Musical” – We join progressive rock band Thotch as they stage their own jukebox musical produced by Cameron Mackintosh and directed by comedienne Kathy Burke. Unfortunately things don’t go to plan as Burke decides to drop all the songs as they were all too long and lead singer Brian Pern is wrongfully arrested under a police operation called Operation Bad Apples.

2 “The Day of the Triffids” – Brian decides to perform his unreleased rock opera The Day of the Triffids, based on the book of the same name, at the peak of Mount Kilimanjaro with a warm-up show at Wembley Arena scheduled for Friday 6 June 2014 with former James Bond actor Sir Roger Moore as the narrator. Unfortunately, things take a snag when manager John Farrow informs Brian that Moore is stuck in New Zealand filming and cannot make it to the Wembley show but has agreed to fufil his role in his hotel room via Skype. After Brian appears on an episode of The Wright Stuff, he is accidentally racist about clothing store Blacks during a conversation with Farrow. He later effectively apologizes during a guest appearance on The One Show. At the show, during the drum solo on the song “Triffid Crackdown”, Brian is busy running to the middle of the Wembley Arena floor when he is met by a Russian security guard who doesn’t let him back in the auditorium until he shows him his bottom so 1980s stars Mark King and Paul Young go on stage instead.

3 “Bi-Polar Polar Bear Aid” – Brian decides to release an album of Christmas songs to raise funds for bi-polar polar bears. Brian enlists the help of musicians such as Status Quo’s Rick Parfitt and Melanie “Sporty Spice” Chisholm. After the album is complete, Brian suffers a heart attack and is taken to hospital where in an interview with documentary maker Rhys Thomas OBE, he announces his retirement from the music industry.

Series 3

1 “Festivals and Fans” – We join Brian as he prepares to celebrate his 45th year in music by performing at the 2015 Isle of Wight Festival and at the 2015 V Festival in Manchester. But when Brian, new wife Astrid and Thotch fan club president Perry Boothe are making their way to the V Festival, the train suddenly stops as a herd of cows had strayed onto the track. Eventually, Brian does perform at the V Festival.

2 “Breaking America” – We look back at Thotch’s unsuccessful attempt to break America: following lead singer Brian Pern’s departure from the group in 1977, the band were forced to hire US singer and “cokehead” Lindsey Simon, whose bottom and nose famously fell out during two of the band’s concerts. While this is going on, Brian is celebrating his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Brian decides not to attend the ceremony because of the backlash that his children, Tallow and Ripple, receive after their purely instrumental song is played on the radio by Zane Lowe: Brian sends Spandau Ballet bassist Martin Kemp to the ceremony in Los Angeles instead. We also see Brian influence 1990s indie music by releasing an album called “Get Real Quick” which included the songs “Maraca Man” and “Poundland Polly”.

3 “The Thotch Reunion” – We join Thotch as they announce they are going to reform for a Wembley Arena concert scheduled for Saturday, 10 December 2015. Brian only agrees to do the concert when manager John Farrow informs him that guitarist Pat Quid has been diagnosed with dementia. Brian then releases his autobiography and gets actor Martin Freeman to narrate the audio version of it just because he “sounds like Martin Freeman”. We later learn that there was a sixth original Thotch member called Bennet St John. The band eventually do the concert but during the performance of “Rock this Nation”, St John appears on stage followed by a security guard and is yanked off. At the end of the series Brian’s bête noire, Peter Gabriel, appears in menacing fashion while appearing to be both the driver and passenger of a kidnap car.

“Keep Trying”

Hats off to Peter Gabriel for letting this happen, including the less than complimentary references to both his life and his records. Try his take on Don’t Give Up with Kate Bush, for example, which plays as Brian wailing “Keep Trying”, or the very rude segueway (pun intended) about the break-through MTV phase (“Spirit Level” for Sledghammer, plasticine-and-all):

Relentlessly and joyously silly, Brian Pern: A Life in Rock flashes light and lashes out at every hole and corner of the pop music business: the cack-handed charity events; the casual fraud; the enormous egos; the lameness of jukebox musicals; the pretensions of genre rock; the shotgun marriage of pop and fashion; the silliness of ‘world music’; the idiocy of pop-stars in protest. Unlike one of Brian’s (own) songs selected by him for Desert Island Discs, “Succulent Chinese Meal,” this show is delectable.

Pern and Gabriel: Segway Face-Off

Now let’s enjoy some Brian Pern from 1980 with Modern Love – er, sorry, “Love is Modern”:

Animal Crossing New Horizons

(On the Nintendo Switch Lite)

[See TVC’s review of an earlier emanation here]A Millennial may annoy with ‘their’ incapacity to deal, and impatience, with technology older than today, but that level of irritation is as nothing compared to that engendered by an adult of the Silent or Boomer generation who says, upon facing an item of technology newer than the fax, “I’ll have to ask an 8 year old how to do that!” (this would be said with an implied LOL if that weren’t something that only the under -10s understand).

Even Lynn Barber of that generally old-person-friendly magazine The Spectator reports proudly (23/5/20), when playing a video game for the first time: “But luckily I have some grandchildren to advise me…first I have to FaceTime grandson Max to ask where to insert the tiny sim card. He manages not to roll his eyes.” I do not manage it. I don’t even try. Why are our elders so proud of this learned helplessness when dealing with post-911 technology? Why do they make no further effort after prodding ineffectually at a screen for two minutes?

“So‘” continues Lynn, “I switch off and go and have lunch. BIG MISTAKE. When I switch on, I have to go through it all again from the beginning because I failed to save it…Max has warned me I must always remember to press the save button….” (Does Ms Barber write her features, columns and books on a slate?) Hence she is “FaceTiming Max again to ask how I am supposed to move.” Maybe just press some of the very few buttons on the Switch? Has the woman no pride? What if Face Time goes down? How long will it take to get to Max’s house in her four-in-hand?

On my bucket list of things to never do before I die (and it will be difficult to do them afterwards, I suspect) is, “do not look at a gadget and say ‘I can’t use that, we didn’t have those when I was a girl, the old way involving slavish levels of labour was better, I can’t understand this stuff, and I can’t be bothered.” So yes I have a Switch Lite, the descendant in a long straight line from my beloved GameBoy, and I play games, all at an age well past Max’s. Children are better at this stuff than are luddites like Lynn, not because of any innate ability or techno-age birthright, but because they have more free time and less on their minds. Nor are they afraid of, or bored by, the Switch and its friends. They’ll give it a go and are curious enough to keep on with a game which they hope will reward them down the track, rather than dropping it in frustration as Lynn did when it was not immediately fascinating. There’s the irony.

And of course my favourite game is the one that Ms. Barber was unconvincingly giving a try: Animal Crossing New Horizons. Ms. Barber really ought to call Max again, or some two year old, and have another go. It is magic. Every day the diligent player collects and sells fruit, waters flowers, talks to villagers, sells and buys, decorates the house, improves the scenery, fishes and catches bugs. But the ability to terraform one’s endlessly mutable island with ledges, waterfalls, bridges and inclines, is the primary improvement on the game’s parent, Animal Crossing New Leaf. Ms. Barber refers to “indentured servitude“. At the beginning of the game there are tasks which must be performed and bells (the in-game currency) which must be earned, in order to learn the mechanics and principles of the game. After that, bells are required for purchases and the building of island infrastructure. Animal Crossing has long described as a capitalist game, but self-improvement and self-determination are the point. The Big Guy is a raccoon, Tom Nook, who seems to live in the main office with his colleague Isabelle, a yellow dog, who may or may not be his wife. The game’s beautiful, seamless graphics and rolling perspective allow the player to build a pretty island peopled with animals in dresses. There are players who strive to make their islands ‘spooky’ or ‘industrial’, but really, if you don’t like flowers and kawaii overload, don’t play.

It is not necessary to go online in order to play. However, being able to visit other islands to sell turnips at a high price (called ‘playing the stalk market’), to collect otherwise unavailable items, or just to look at some of the truly incredible works of art which the game has spawned around the world, make it worth the $5.95 per month (or $29.95 annually) Nintendo membership. Also, there’s a really, really clever grandchild common to us all. Its gender free name is Google. You really won’t need to Google to learn how to move or attend to the basics, they are self evident, or learned through the early ‘indentured servitude’, if you put just a little effort in. Beyond the basics, though, the game is so potentially complex that you might want to google Feng Shui principles for your house or the genetic code of the flowers if you wish to breed hybrids.

The gameplay is superbly constructed. Shadows move according to the time of day, items are sharp in-close focus, flowers and trees wave independently in the breeze. Your island operates in real time, with southern or northern hemisphere seasons and regular ‘visitors’. Nintendo sends updates for short-term events, such as cherry blossom season.

There are minor flaws – repetitive dialogue, some clunkiness in the terraforming mechanics and insufficient design spaces. But this is a magnificent game, A thousand kudos to the Nintendo boffin who said’, ’Let’s make a girl’s game‘,* playable every day without boredom for a year, free from combat or racing, devoted to design and useful living’ and a million to the one who says, “Let’s make another game along the same principles, but different. Not everyone playing video games wants to shoot stuff or look at boobs.”. May that next game sell millions: one of those copies will be mine. And I’ll play its descendants on the remote descendants of that beloved GameBoy for as long as I am able.

[*yes, we know. Max can play too.] Continue Reading →The Trial of the Chicago 7

(Directed by Aaron Sorkin) (2020) (Netflix)

Ah, Hollywood. They’ve been dreaming-up stories of white hats vs black hats since the days of Tom Mix. In this rather ho-hum court room film, there are plenty of black hats to go around: John Mitchell, vindictive Nixon Attorney-General, who wants a Show Trial of the Yippies: His sundry henchmen from the Justice Department; Chicago Mayor Richard Daley and his police goons; Chicago undercover cops who infiltrate the activist groups and in some cases shamelessly tempt them; Judge Julius Hoffman (played by that all-purpose villain of the legislative, executive and judicial branches of government, Frank Langella); the enthusiastic purveyors of the Vietnam War.

Setting a film around a trial is a convenient organizational ploy: it lets you flash-back, flash-forward and flash-sideways, and a trial’s adversarial nature keeps you in tune with the white and black hats, even when you forget (or don’t care) who is whom.

The really interesting story was the lead-up to the confrontations at the 1968 Democratic Convention in ‘Fort Daley’ (a year, like ours now, graced with the unreliable rubric “unprecedented”), involving endless political permutations, jockeying, threats of violence and rebellion, and the cataclysm of LBJ’s decision not to seek re-election, but the film skirts all that, possibly because it wants to avoid showing the insurgents’ sizeable chunk of blame for the resulting shambles*, albeit less than Daley’s over-the-top, stupid, brutal, almost berserk police force.

The peace-in-Vietnam activist groups descending on Chicago that summer included the Yippees, led by Abbie Hoffman (no relation to the judge; described thus in An American Melodrama – “With his long, curly black tresses and sharp, intelligent face he looks rather like a Semitic Charles I”), and Jerry Rubin; David Dellinger (Quaker and head of ‘National Mobilization’), his lieutenants Rennie Davis and Tom Hayden; some minor ‘conspirators’ (Lee Weiner and John Froines); and the founder and head of the Black Panthers, Bobby Seale (who was there by accident, gagged and bound by the Judge and removed during the proceedings, turning the Chicago 8 into the Chicago 7). We don’t learn a hell of a lot about any of them, and we certainly don’t find ourselves on the edge of our seats fearing for them: they’re here to be monstered by the black hats, and absolved in the closing credits.

As for the trial itself, starting as a circus in the autumn of 1969 and ending as an obsequy several seasons later, it is mostly a series of snappy vignettes; snappy glances and grins, bon mots, gavel-banging by the frustrated and impotent old judge. The defendants range from suited Quaker, to clean-cut organizer (a crypto-Obama, if you will) to goofy hippys, and a real terrorist. Their inter-action is strictly by the numbers however, as are the performances by the attorneys for both sides (Mark Rylance doing his version of Thomas Cromwell in a cheap suit), plus Sacha Baron Cohen playing a dramatic role in a comedic way. Eddie Redmayne, as Hayden, comes across like an earnest, worried sufferer in an antiperspirant commercial. Michael Keaton appears in a cabaret turn as Ramsey Clark. The whole melange fails to satisfy, persuade, or inform. At the end, we shared the contempt both Hoffmans felt and showed throughout.

Footnote

[* There were in fact a number of calls that might be characterized as amounting to incitement. For example, Bobby Seale called on Chicago demonstrators to “go barbecue some pork….pick up a crowbar. Pick up a piece. Pick up a gun…If you shoot well, all I’m gonna do is pat you on the back and say ‘Keep shooting.’ You dig?” Jerry Rubin held formal seminars on the construction of Molotov cocktails. Hayden spoke from Paris in the middle of the year of a revolutionary takeover of Chicago. During the drama of the convention, someone raised a Vietcong flag. After Rennie Davis was beaten to a pulp by police, Hayden called on the crowd: “Let us make sure that if blood is going to flow, let it flow all over this city.” (He forgot to say “our” before “blood”, according to the film.) Fires were lit in Lincoln Park and Grant Park. In Playing With Fire, Lawrence O’Donnell observed (p.346): “The protestors kept raising the rhetorical stakes. They informed Daley’s office that three hundred thousand protestors would arrive in Chicago even though they expected less than a hundred thousand. Rumors flew of plans to put LSD in the Chicago water supply, attack the convention hall, and trash high-priced stores on the Loop. “The North Vietnamese are shedding blood,” Tom Hayden said. “We must be prepared to shed [our?] blood.” MOBE assembled a raft of protest marshals to teach protestors not only how to resist passively but also how to fight back if necessary, and how to break through police lines.”] Continue Reading →Wagner’s Parsifal

(The Music of Redemption) by Roger Scruton (2020)

Some Brief Words From the Wise on Holy Communion

“…it belongs to that class of myths which have been dramatised in ritual, or, to put it otherwise, which have been performed as magical ceremonies for the sake of producing those natural effects which they describe in figurative language. A myth is never so graphic and precise in its details as when it is, so to speak, the book of the words which are spoken and acted by the performers of the sacred rite.”*

“It would indeed be impossible to devise a mystery capable of keeping men more effectually within the bounds of virtue.“‘**

“Combined with the recollection of the Passover and of the first covenant, [The Eucharist] is lost in the remoteness of time; it reproduces the earliest ideas of man, in his religious and political character, and denotes the original equality of the human race. Finally, it comprises the mystical history of the family of Adam, their fall, their restoration, and their reunion with God.”^

Working Out the Weirdness of Wagner

In these times of pestilence, it has been an additional blow for The Varnished Culture to have suffered cancellations of the production of Lohengrin in Melbourne and Opera Australia’s production of The Ring in Brisbane. First World problems, we know, but it brings additional sadness. Still, there are compensations, including Roger Scruton’s last book. While Roger’s writing style makes the reader feel s/he is walking through 2 solid feet of brimstone and treacle, it is a pretty wonderful, dense book, with very many good things to find about Wagner’s last, and possibly his best, and indubitably his weirdest, opera: Parsifal, first performed at Bayreuth on July 26, 1882 under the auspices of the Maestro’s catchy tagline – ”ein Bühnenweihfestspiel.”

Roger Scruton has thought long and hard about this work and pondered the nature of religious/spiritual belief, finding therein a kind of soulless solace. Wagner was something of a one-man cult who borrowed (with sublime irreverence) from myth to create, in his music-dramas, a counter-myth: not a God, but a ‘Godliness.’ Where Dostoevsky strove to ‘find the man in man,’ Wagner – certainly not a Christian – looked for God in man. It was his heroic quest, and reflective of his respect for religion and myth as spiritually true. He read deeply in the grail oeuvre: Troyes, Boron, Eschenbach, Malory, and rejected the mere mercantile world in which he so often became personally embroiled, desiring instead, or to add, a heroic consecration. Wagner is a sort of Secular Church.

Certainly, he is far from the Christian archetype. Art trumped God, or, rather, was God. Scruton cites Wagner’s 1880 essay ‘Religion and Art’: “it is reserved to art to salvage the kernel of religion, inasmuch as the mythical images which religion would wish to be believed as true are apprehended in art for their symbolic value, and through ideal representation of those symbols art reveals the concealed deep truth within them.” The central paradox of Parsifal, that clings to the mind like chewing-gum to the sole of a shoe, is that Wagner, rather prone to self-pity, saw himself as the Great Redeemer of German and indeed World Art. The termination of the show brings forth the phrase ‘Redemption to the Redeemer.’ A plausible case can be made for this, though Scruton cites Nietzsche on the obsequies when the Maestro died: “Many (strangely enough) made the small correction [to the wreath]:”Redemption from the Redeemer.” One breathed a sigh of relief.” And many no doubt later inhaled through the mouth at the inevitable stench of Hitler declaring he had built his own deification project on the footings of Parsifal.

Synopsis

Scruton repeats himself a fair bit in this book (it probably needed some final polishing at the time of the author’s death early this year) and whilst he gives a potted synopsis of the opera’s plot (invariably a bad idea) in his first chapter, he gives an even longer exegesis in the next. One wanted to close the book and go watch the opera. Still, along the way he interprets the action with such learning and erudition that it becomes an invaluable annotation both to the score and the libretto. For the uninitiated, we’ll sketch the story here in its Trinity of Acts:

ACT 1

King Titurel was given the Holy Grail to keep safe at Montsalvat, guarded by knights headed by the King’s son, Amfortas. One knight (Klingsor) went off the reservation and was outcast, even after emasculating himself to simulate chastity, or recover it. In a fury, he created a magic castle of earthly delights, with which he tempted and corrupted the knights, including Amfortas, who was seduced by Kundry (Klingsor’s love slave) and ambushed by Klingsor, who wounds him with the Spear that rent Christ’s side on the Cross.

Now Amfortas is house-bound with a wound that won’t heal (his musical motif “wobbles on its augmented triad as if every note were a jolt of pain“), and Montsalvat has fallen into despond. Kundy drops in with some balm – she’s torn between loose and clean living, but the senior knight, Gurnemanz, says only a holy fool can cure Amfortas and the rest. Enter Parsifal, in trouble for straying in the sacred grove and shooting a swan into the bargain (Lohengrin wouldn’t have done that). On questioning, he appears to be as incoherent, indifferent and grumpy as Kaspar Hauser. He’s taken to the Grail Hall and given marching orders.

ACT 2

Parsifal wends into the Waste Land of heathen Spain, cuts his way along the ramparts of Klingsor’s Castle and into the garden, where he resists the flower maidens. Meanwhile, evil puppeteer Klingsor has directed Kundry to set him up as they did Amfortas. Kundry (the serpent in the garden, linked to Tannhäuser as Parsifal is to Lohengrin) is wracked with guilt (having mocked the man on the cross, and sundry other misdemeanours) and filled with passionate yearning and intensity, but Parsifal, in a remarkable musical sequence, rejects her, deflects Klingsor’s spear, and with a papal gesture turns Klingsor’s edifice to dust. Thus he paves the way for Kundry’s eventual redemption, as she has paved that course for him. Meanwhile, we imagine Klingsor as Herman Hesse imagined someone like him:

“Wandering long, I have done and suffered much,

Now at evening I sit, I drink, and wait

Fearfully till the flashing scythe

Parts my head from my leaping heart.”^*

ACT 3

Good Friday. Parsifal, at the end of a long wander, meanders in to Montsalvat; this time he has the spear. He absolves Kundry, even though she reminded him his neglect killed his mother. On a roll, he attends the Eucharist and heals Amfortas by laying the spear on his wound. Kundry dies cleansed, expiated in holy service to the Grail and its temple, a true reformed heroine. Time (chronos) becomes space (kairos); even Titurel briefly resurrects. The Grail is illumined. Parsifal, the holy idiot, has been transformed into a wise man through compassion (durch Mitlied wissend).

Themes

For The Varnished Culture, Parsifal is Wagner’s most wondrous and enigmatic work, containing his most subtle and beautiful music. If you are not in the right mood, however, it can strike as trite, pretentious, overblown, and almost nauseating; in the wrong frame of mood, you wish to eliminate metaphysics (Scruton sums up some opinions of the work: “provocative, holy, religiose and blasphemous“). In actual fact, Parsifal, more than any other of Wagner’s works, needs to be treated with reverence: no Regietheater treatment can work in this space, as Scruton points out.

But what does it all mean? That which cannot be articulated, in sum, but Scruton (who has been described as “the knight errant of western civilization“) can clothe the central mystery with fine words and thoughts, woven into a complex portrait of musical structure, the collision between myth and humanistic philosophy, and the mystery of redemption. From the initial three chapters:

“[Wagner] understood, as few before or after him have understood, that the sacred, the sacrificial and the sacramental are aspects of a single world-changing endeavour: the endeavour for which ‘redemption’ was Wagner’s name. He had the uncanny ability to explore beneath our sophisticated rituals, in order to discover their roots in the pre-history of humankind. And in doing so he revealed what our rituals mean. Wagner regarded the concept of the sacred as indispensable to human relations. But he also believed that it is we who render things sacred, and that no God has a part in it.” (at pp. 37-38).

“The music (Act II) weaves together the sacred and the desecrated, the pure and the polluted, the giving and the refusing. We hear the holy as it changes to the unholy and yet remains the same. Such enharmonic changes of the passions, are delivered by the enharmonic language of the score, and the uncanny sense of unity between all that we hope for and all that we fear is in the end what Parsifal is about. ‘You know where to find me,’ says Parsifal – namely, in you.” (at pp. 52-53).

“…the Percival legend is given an allegorical form, telling just the same story as the books of alchemy, and as the tales of Oedipus, Antigone and the rest – the story of the self in its search for the anima that completes it, healing the wounds of separation from the mother, so as to become the ‘divine son of the mother’ as in a pietà.” (at p. 70).

Roger Scruton’s fourth chapter, ‘Sin, Love and Redemption,’ parses the real meaning of Wagner’s explicit and implicit references to compassion, sympathy, empathy, agape, as forms of endogenous knowledge. Wagner might appropriate godliness to humans, “But human creations include some very real and lasting things, such as St Paul’s Cathedral.” “The gods come about because we idealise our passions, and we do that not by sentimentalising them but, on the contrary, by sacrificing ourselves to the vision on which they depend. And it is by accepting the need for sacrifice that we begin to live under divine jurisdiction, surrounded by sacred things, and finding meaning through love. Seeing things that way, we recognise that we are not condemned to mortality but consecrated to it…the redemptive quality of sacrifice does not consist in conveying us to another world where we live in bliss for ever, but in transforming our vision of this world.”

It cannot be right that “In the innermost core of Wagner’s idea of redemption dwells nothingness” (Theodor Adorno, of whom we have spoken in sorrow before, and whom Scruton deals with justly and dismissively). Rather, the substance of Parsifal, whilst elusive, is reflected in Scruton’s peroration at the conclusion of his last chapter of substantive thematic discussion (later chapters concentrate on musicology, including enharmonics, consonance and tonal grammar, and the leitmotifs, beyond the scope of this review and beyond the wit of this reviewer):

“We have been called not to explore the world, but to rescue it. In doing so we emerge from our trials and conflicts in full possession of our social nature. Like the Redeemer, we make a gift of our suffering, through an act of consecration that brings peace to us all. Whether or not there is a God, there is this hallowed path towards a kind of salvation, the path that Wagner described as ‘godliness’. That is the path taken by Parsifal, and it is a path that is open to us all.” (at pp. 124-125).

NOTES

[* J.G Frazer, The Golden Bough (1890), chapter 612.] [** Voltaire, Questions sur l’Encyclopedie (1770-1774), Book IV.] [^ Chateaubriand, The Genius of Christianity (1802), Chapter VII.] [^* Hesse, Klingsor’s Last Summer (1920).] Continue Reading →How to Lose Interest in 15 minutes

“How to Lose a Guy in 10 Days” (Directed by Donald Petrie) (2003)

At a cottage in the Barossa Valley, The Varnished Culture found 4 Rom-Coms to watch, and chose this one, largely based on the likeability of the two leads (and Kate was in a decent film about magazine writers once). We liked them less after 15 minutes: they’re too old for these shenanigans, and too old to, seriously, strike job-on-the-line wagers to win, woo / spurn a partner in record time. She has to start a romance and dump him; he has to win her. She conducts herself such as to almost persuade us of the mythical patriarchy; he has spontaneous orgasms at the prospect of tickets to see the Knicks play at the Garden. All this to provide the bases for a soft magazine piece and a new tagline to sell diamonds. Despite the odd funny bit, and a decent cast, the scenes, the script, and the characters, are all dreamed-up by idiots – also not a little slimy – and by the way, basketball has to be the dumbest sport ever invented!

Continue Reading →