The Varnished Culture's Thumbnail Reviews

Regularly added bite-sized reviews about Literature, Art, Music & Film.

Voltaire said the secret of being boring is to say everything.

We do not wish to say everything or see everything; life, though long is too short for that.

We hope you take these little syntheses in the spirit of shared enthusiasm.

Safe

(Written and directed by Federico Maria Giansanti of FMG, an Italian independent theatrical producer) (2020) (A one-woman performance, filmed play, link below)

At an indeterminate time, in an isolated mountain hospice a young nun (Valeria Wandja) is alone, taking care of two people. The other characters, – a man Paul (“a pure soul” who “takes a bit longer sometimes”) and a bedridden, terminally ill patient, Mrs Parker – are neither seen nor heard. We know them through the nun’s responses to them. The three are the final survivors of a larger community. The nun (“Sister Daisy”, although her name is not heard in the production) calls out to those others who died of an “evil, silent, invidious virus” which is returning her world to a place of “prehistoric desolation“. Communications with the larger world are “shut”. We are privy to her prayers and her spoken thoughts.

Wandja is as alone as Sister Daisy, and her solo performance, in precise, accented English is a tour de force. It lacks nuance perhaps, but Wandja carries the physical burden of the play as Sister Daisy carries the eschatological burden of the three doomed lives, and their souls.

The stage is sparsely lit, barely furnished, the corners and background dark. The black, beige, and red pallet; the wan face of the white head-dressed nun, at times recall a Dutch painting. The freezing exterior is effectively represented by a small flight of steps, and plastic for snow. There is little sound beyond the nun’s voice in prayer and in response to the unheard voices of her charges. There is occasional baroque music, which enhances the slow and mannered mood. Once, bells are heard – are they far down the mountain or outside of the theatre?

Sister Daisy enters the stage carrying the candle of her faith. Between scenes she is spot-lit praying aloud behind a rudimentary red cross. By the end the candles are gone. The food and heating went long before. Sister Daisy relentlessly reassures her charges, “I’ll take care of you“. She cleans, washes, disinfects and cooks what little they have. Her self-abnegation, work and faith are the only bulwark against complete nihilism. She says, “I want to believe everything is going to be fine, even though I know it’s not” and, “It’s going to be alright. We have to have faith.”

Daisy is pious but not a saint. Frustration and bewilderment live side by side with her exhaustion and fear. She answers a question from Mrs Parker with, “for the nine-thousand millionth time…” In the face of a particularly devastating event she swears, screams and shouts an ironic version of “He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands.”

The flashback scenes to the nun’s unhappy childhood and adolescence would be better excised: they are somewhat predictable and break the mood. Her profound thought (that to live a life of ease, after much suffering, would have been to neglect herself) would be more thought-provoking without the somewhat histrionic setup.

As the nun despairs, her courage and faith remain but she re-considers her purpose. She has done what was asked of her, and has helped others. She questions her motives: “their gratitude fed me“, and “to be honest their deaths have relieved me.” She says that she would “do it all again, but would she be safe?” Of course, we must ask, ‘what is safety?’ We shall all die. Daisy prays: “Stay home. Stay safe. The last words we’ve heard. “Please help me understand these words.”

“Safe” is a fine example of the capacity of theatrical minimalism. As a performance which premiered online at the Great Salt Lake Fringe Festival and won both the “Best of Fringe Festival Award” and the “Audience Choice Award”, it is also an example of how the arts can be kept alive at this time when we are told, “Stay home. Stay safe”. Giansanti and Wandja are both likely to do great things.

A recurrent theme, which resonates with effect in these pestilential times, is that of hope. And, as Emily Dickinson reminds us:

“Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul,

And sings the tune without the words,

And never stops at all...”

Continue Reading →Knives Out

(Directed by Rian Johnson) (2019) (Foxtel)

Paterfamilias Christopher Plummer (in a customary sleek, silky, telephoned-in performance) has gathered the family, hinting at some amendments to his testamentary dispositions (shades, but only shades, of Agatha Christie’s After the Funeral and Hercule Poirot’s Christmas). When he turns-up dead in his cramped but sumptuous study, throat cut, suicide appears likely, at least to the police in charge of the case. But wait! What’s James Bond doing in the background, tinkling at the piano? It’s private sleuth Benoit Blanc (Daniel Craig, joining the Honour Board of British actors undone by attempting a southern drawl in public: think Michael Caine in Hurry Sundown or Richard Burton in The Klansman). Blanc has been summoned by persons unknown (perhaps the casting directors wanted to remain anonymous) and he has a fine time carrying out some Columbo-style harassment of the old man’s nurse, ‘Go’ partner and possible amanuensis, Marta (Ana de Armas, as incongruous here as was Pilar Estravados in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas).

The family were all, of course, a disappointment to the old fellow, and played accordingly to type (out of a decent cast, Don Johnson appears the only one to be having a bit of fun with the role) and we have to roll around the inanities of will-reading, recriminations, reconstructions, interminable interviews, the odd car-chase, and various twists before the inevitable (and somewhat incomprehensible) exposition.

The gang’s all here, and ready to rumble (Jaeden Martell, Riki Lindhome, Michael Shannon, Don Johnson, Jamie Lee Curtis, Toni Collette, Katherine Langford.) (Unfortunately, much of the film was like this).

Stylistically, the film owes a lot to Sleuth, Deathtrap and Clue, but there’s not much of any of those in the way of substance. This film has proved popular, just as the Masque of the Red Death was during an earlier plague. Hopefully not-untalented film makers will resist the temptation to farrago a sequel: after all, the film contains its own two best critics, who express themselves far more eloquently here than we can. After the aforesaid car chase, detective Lakeith Stanfield (seen to advantage in Get Out and less so in Sorry To Bother You) describes it as the silliest ever. And Marta cannot stop vomiting. Knives Out is neither classic whodunnit nor comedy-thriller; neither police procedural nor dramatic chase; neither drawing-room melodrama nor genre spoof. It is refreshing to have a film that defies categorization, if you’re a librarian: but to most viewers, a film that truly does not know what it is supposed to be must go back in its box.

Continue Reading →Solid Gold

The Glenelg Football Club 2019 Premiership Yearbook

(By Peter Cornwall, Andrew Capel & Zac Milbank) (2020)

We have banged-on far too much about the Glenelg Tigers’ brilliant championship season of 2019 – you can read all about it here.

So let someone else do it, only better: “Solid Gold” by experienced professional sportswriters Cornwall, Capel and Milbank, is a great keepsake for fans as well as a comprehensive record of a thrilling season. Beautifully designed in burnished gold and jet black, shaped like an EP vinyl record cover, it is especially evocative in this plague year.

For once, the advertising for this book is no bumpf, so we cite from it here: ‘SOLID GOLD captures the action, emotions, memories and celebrations from the Bay’s unforgettable drought-ending 2019 Premiership season, culminating in winning its fifth flag at the Adelaide Oval against arch rival Port Adelaide.’

Along with an introduction by Club President and Great, Peter Carey, it features a superb game-by-game wrap of the minor and major rounds (by Cornwall), player profiles and statistics, a review of the teams in all competitions, Hall of Fame inductees, and accounts of a club coming up for air after years of stultifying debt and defeat. It is packed with great photos by the Ansel Adams of Sport, Gordon Anderson.

While Solid Gold serves mainly as an aide memoire, it contains one actual revelation. We will only summarize it here. In an article, “Honesty is the best policy,” Zac Milbank reports that the Senior Coach had promised to tell the team what it needed to hear, and he invited ‘Honest Feedback‘ in return. Be careful what you ask for. As he admits, Mark Stone could at times become apoplectic when things weren’t carried out as he wanted: “…while I’m sure all coaches get frustrated, it would get the better of me. I would come out in a way where that frustration would bear itself in a pretty unproductive way.”

So mid-way through the season, the leadership group went to the Coach and outlined the issue, and Marlon Motlop told him, “You need to plan for this.” It takes actual courage to tell someone that out-ranks you they have a problem. Yet as we saw, and the book shows, the 2019 team had more than skill, smarts, fitness and grunt – it had real courage as well. And it would also have needed courage, and maturity, for the Coach to take that feedback on board. It was a bridge that had to be crossed, and strikes us as an influential moment, since the Tigers were sorely tested in the last half of the year and invariably found a way to cut through.

The Varnished Culture recommends this book to Glenelg fans over the globe. (Tigers fans should spoil themselves when they can.) And buy some extra copies: Christmas isn’t far away…

Continue Reading →The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser

(Directed by Werner Herzog) (1974)

[He did exist: and his back story, true identity, and untimely end remain a mystery. Various suppositions and theories have all been unmasked as absurd. Be that as it may, the myths around Kaspar offer a useful trope for film-makers. And in the case of Werner Herzog, it inspired his best film (along with Aguirre, The Wrath of God and Fitzcarraldo). The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser features all of his most infuriating flourishes, yet it manages to move and fascinate. Its a kind of Pygmalion-meets-The Wild Child-and-Bad Boy Bubby, with a dash of Ruprecht-the-Monkey-Boy from Dirty Rotten Scoundrels.]It opens with Kaspar, an adult with arrested development, chained in a stable, fed on bread and water, and playing with a wooden horse. This in itself is ludicrous: he would be in pretty poor shape if this was his diet for any extended time. Eventually his anonymous ‘carer’ teaches him to walk and speak the odd word: he is sent packing to Nuremberg with a letter of introduction (Herzog insists on a ponderous reading and transcription), comprising two historically real (but fake) notes: “He was brought to me October 7th, 1812. I am but a poor laborer with children of my own to rear. I beg you to keep him until he is seventeen. He was born on April 30th, 1812. I am a poor girl; I can’t take care of him. His father is dead.”

As in all foundling stories, our lad is taken in and given a good classical liberal education, featuring a hefty dose of Christian dogma, which sits ill with the young philosopher, more naturally inclined to a Rousseauian world-view (the film paints him as a sort of seer, a home-made logician, the town anchorite, a Steppenwolf in opposition to and an indictment of bourgeois society).

Eventually he acquires a place in village society; he is even feted by the great and good (and the very peculiar Lord Stanhope). But essentially he remains a rough and unready outsider; strange, stubborn, and gruff: freed from his cage, he dreams only of its bars (and similar prisons: the pilgrims struggling up the mountain, the blind man leading a caravan out of or further into the wilderness, the stork snaffling a frog). His end comes almost as a relief, to him, the villagers, and the viewer. But along the way, apart from the deliberately stark and disjointed manner in which Herzog unfolds the mysterious events, one is captivated by the director’s most audacious touch: the casting of a gadabout orphan street performer with mental issues, known only as Bruno S. Herzog copped flak for this – it was considered exploitative – but Bruno’s role is to be incongruous and this he does magnificently, with a vast, grotesque and completely authentic collection of ticks, shrugs, blurted bon mots, crazy sideways glances and catatonic, faux, brown studies. His performance supplies the revelation that the unresolved life of Kaspar Hauser lacks.

Continue Reading →Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga

(dir. David Dobkin) (2020) (Netflix)

If you love the Eurovision Song Contest, read on. If you hate, or are merely indifferent to it, stop reading now. No-one likes that kind of negative weirdness.

Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga was scheduled for release in May 2020, in order to coincide with the final of the real Eurovision contest in Rotterdam this year, but the final was cancelled, tragically, due to some little pandemic or other. Who wouldn’t risk a bit of respiratory failure for the chance to see acts like this –

Thank goodness that at least we have this gentle homage, which partly fills the Eurovision-shaped hole in our Covid-19 lockdown days.

Will Ferrell wrote the script with Andrew Steele. Ferrell plays Icelandic singer Lars Erickssong who, as a small boy, was immediately cheered-up by ABBA banging out Waterloo at the Eurovision final in 1974. His previously silent young friend Sigrit Ericksdottir (Rachel McAdams) is similarly inspired to sing and the two spend the next indeterminate number of years as the duet ‘Fire Saga‘ working on unsuccessful Eurovision entries. They may be in a basement, but in their minds they are performing on dramatic fjords and lava fields in true Eurovision garb. (Whom do we have to blame for winged pseudo-Viking helmets? Surely that’s not Richard Wagner’s fault along with everything else?)

One of the members of the team who organize the 2020 Icelandic competition for entry to the Eurovision Song Contest (an evil banker) does not want a good Icelandic act to enter the contest, because they might win, and then Iceland would host the final in 2021. Nor is this idea original. The idea that hosting Eurovision would bankrupt a country (in this case Ireland) was used to great effect in the A Song for Europe episode of the TV show Father Ted. (Fire Saga‘s various attempts at crafting a Eurovision-winning song are good, but sadly, lack the vital force and sheer loveliness of Ted and Dougal’s “My Lovely Horse”.)

Due largely to the machinations of the evil banker (again, owing something to Father Ted), in 2020 Fire Saga make it to the final in Edinburgh, Scotland (an unlikely location given the unpopularity of the UK in the Eurovision world).

Will Ferrell is obviously too old, hirsute and rounded to make it as a Eurovision type of guy. His earnest closeups, wild hamster-wheel riding and wire-flying are very funny indeed. His deluded and vain Lars could be the cousin of Ferrell’s deluded and vain ice-skating champion Chazz Michael-Michaels in Blades of Glory. Lars could also be a cousin of Ferrell’s much sweeter North Pole elf character Buddy in Elf. (Fittingly, Sigrit appeals to the Icelandic elves for help.) And Lars’ grumpy Dad recalls Reese Bobby from Talladega Nights. Just like Blades of Glory and Elf, there are no surprises in The Story of Fire Saga. And yes, the ending (involving a very placid baby, Lars’ visceral loathing of American tourists, and a song called “Jaja Ding Dong”) is schmaltzy but fun.

The two leads are fine and do some of the singing themselves. Dan Stevens (below) is especially likeable as the not-so-evil Russian, Alexander Lemtov. Melissanthi Mahut plays the Greek contestant, whose only reason for existence in this film appears to be so that she can pull off some clothing in time-honoured Eurovision style. This film could be criticized for that, and for casting a young and attractive actress with Ferrell, but that’s Eurovision, and in any event, the film includes plenty of the usual bare-chested, excessively groomed Eurovision-style men, if you like that type of thing. Demi Lovato does a rather odd turn as Iceland’s favourite for the contest. Pierce Brosnan amuses as a dry Icelandic fisherman who is ashamed of his son Lars for the most part and is generally known in their small town for being ‘handsome’ and a womanizer (Lars is fairly certain that Sigrit is not his sister).

There is an excellent musical number set in a castle, clearly intended to be used for promotion. It’s a ‘spontaneous” “song-along” where the camera veers through a house full of movie and real Eurovision contestants singing and sparkling. They make Cher’s Believe listenable and Waterloo not as tired. The hirsute Conchita Wurst is in excellent voice in this scene. Netta is as inexplicable as ever.

The costumes are fine, for the most part, if unimaginative by Eurovision standards (although we did wonder why it looked as if Rachel McAdams had had to do her own hair). Lars flies from Edinburgh to Reykjavik in a sleeveless puffy vest, tight trousers and spangled platform heels – all silver. The stage numbers are almost as flashy and ghastly as the real thing – we waited for – and got – the dry ice smoke, but were disappointed in our hopes for a contortionist.

Unlike the smooth and over-produced song contest, Eurovision the movie is clunky (starting with the name) and uneven. But also like the song contest, it is predictable, sugary, amusing, kind, funny, self-aware and earnest. Iceland is beautiful, Edinburgh is beautiful. Eurovision is beautiful. Any film that celebrates them is a must-watch.

[And Another Thing: P agrees: this film is as simple and un-cerebral as it could be if not comatose, but great fun nevertheless and even kind of moving, in a sweet, elfin way. The film-makers have caught the Euro-feel and the essential warmth and collegiality of the contest. In a year without Eurovision-for-real, it is to be welcomed and congratulated.] Continue Reading →The Circus

(Showtime) This documentary (more of a fly-on-the-wall ride-along) looks at the bizarre 2016 primaries and general election in the US. The access to the candidates is terrific, even better than the Pennebaker piece, but you get the sense that whilst Donald Trump kept on winning, his rivals kept attacking the Republican candidate next in line, as they clearly couldn’t accept such an outlier: denial of clear facts over bruised feelings aka derangement syndrome, replicated even after he was endorsed by the GOP and contested the election against Hillary Clinton.

The footage is king here; but the analysis is also vastly entertaining, as three old political hands, meeting in interminable cafes over what appears to be lethally unhealthy food, opine and refine as they go. We recommend the first series (2016), all 26 episodes: the subsequent series concentrate on the Trump Administration, a matter unlikely to be of reliable guidance, as the Donald tends to drive everyone else mad. History will have to judge that experiment, a long way down the road.

Continue Reading →A Bigger Picture

By Malcolm Turnbull (2020)

To re-tell a recent joke, with apologies to Frankie Boyle, Turnbull’s memoir is not like Turnbull the man, in 2 respects: it has a spine, and you may not want to put it down. Yes, we’re on record as not being Malcolm fans, for whom this pretty well written and interesting book is designed, though it holds wider interest in following the August path of destiny for Australia’s 29th Prime Minister, a path strewn with garlands and fleeting triumphs, told in a voice of peerless self-confidence, well described by Jonathon Green in the Sydney Morning Herald as “first person magnificent.”

In a soft (the creators of Frontline would have called it a ‘flirt-piece’) yet revealing interview by Leigh Sales on ABC’s 7.30 programme, Mr. Turnbull kept stressing that his (legendary) ambition had a purpose…”I always wanted to get things done…to effect change, to effect reform.” Leaving aside the risible claim that change and reform were effected on his watch, this No-Power-Without-Purpose mantra sums-up Turnbull, explains his formidable personal trajectory, and demonstrates that he was never a true conservative.

As the late Roger Scruton explained, “The subjection of politics to determining purposes, however ‘good in themselves’ those purposes seem, is, on the conservative view, irrational. For it destroys the very relationship upon which government depends. This, the conservative might say, is the true source of the absurdity of communism: that it saw society entirely as a means to some future goal. Hence it was at war with the very people it had set out to govern.”*

YOUNG MALCOLM

Mr. Turnbull’s book is in 5 parts: beginnings (1954-1982), his legal and business activities and entry into politics (1983-2003), his rise to leader of the opposition and fall (2004-2013), his time as loyal (yes, that’s what he says) servant of the Abbott Government (2013-2015) and his stint as Prime Minister (15/9/2015 – 24/8/2018).

Malcolm was formed, uno ictu, such that he was never really a child. Here are some examples of his time in short pants: “We rented [in Vaucluse]…from a frightening old man called Clarrie Ball, who lived next door in Flat 1 with a snappy dog that didn’t like me…”

“The Sydney Grammar boarding house at St Ives was a brutal, badly managed place. Bullying was rife and I was particularly unpopular.”

“Next door was the classroom where he taught 1A – the brightest of the new boys, including me.”

“I loved history, often embarking on my own independent research…I probably didn’t know the word for it then, but it was the start of a lifelong interest in historiography…”

“One master was especially sleazy. When I was 14, my friend Ted Marr and I went to see Alistair Mackerras to complain about him. Alistair was an unworldly man, an innocent in many ways, and he couldn’t understand what our concern was. I told him that if he didn’t move the master out of the boarding school, I’d walk across the park to see the chairman of trustees, whom I knew to be the very grand Sir Norman Cowper, senior partner of Allen Allen & Hemsley.”

(In other words, he was a prig and a bully from early on.) He was unlucky in his parents: Coral Lansbury left for another man when he was only 10, and rarely kept in touch; she is remembered here with justifiable coldness, and may help us understand his extremely close bond to wife Lucy. His father, a gadabout and ultimately successful hotel broker, whom he adored, died in a light plane crash when the author was 28.

The co-captain and senior prefect “…left Grammar filled with confidence, ambition but above all curiosity.”

He went to Sydney U and immediately sought to be elected editor (he lost to a communist) and immersed himself in political journalism. His 1975 obituary for labor firebrand Jack Lang is somehow apt: “He was convinced of his own rectitude and regarded anyone who disagreed with him as a saboteur.” Turnbull found attractive the reportage “where the journalist is right there in the centre of the story.” He cold-called channel 9 and radio 2SM and got a parliamentary round. “Sitting in the press gallery, watching the politicians clash in the parliament below, I thought, I could do better than that.”

DABBLING

Turnbull was, along with his bête noire Tony Abbott, that quaint curio, a Rhodes Scholar, despite the former’s disdain of “imperial fantasy.” He combined his study of law with running highfalutin errands for Kerry Packer and earning on the side as a Fleet Street hack. (You certainly could not convict Turnbull of laziness). On return to Australia, shortly after rejoining the Liberal Party, he ran for pre-selection in the blue-ribbon Liberal seat of Wentworth, at the tender age of 26. He lost narrowly, not having mastered the art of branch-stacking, which he perfected in 2004. But then he had become Packer’s consigliere, advising on diverse elements of that panjandrum’s empire, including his inquisition by the Costigan Royal Commission (“…I’d resolved to see it through, believing firmly that nobody was better able to get him out of the mess than me.”)

By a combination of grunt work, threats and dirty pool, Packer was vindicated. And then another triumph: Turnbull’s victory in the over-hyped Spycatcher case, an ill-judged attempt by the British Government to stop the publication of a poor book that had pretty much washed-around the public domain already. Turnbull made more of this rather ho-hum legal victory than Nixon did of the Alger Hiss case.

RICHES

Still, he was on his way. Having staked a name and reputation for himself, and free of Packer, he formed a lucrative partnership with Nick Whitlam, and spent the next several years making a lot of serious money – which is impressive if all you want to do is make a lot of money. He writes: “Nick Whitlam became unhappy; Neville [Wran] and I never understood why.” Note that Whitlam himself riposted in the 25/4/20 ‘Weekend Australian,’ “Not true. Neville knew. Everyone in the firm knew. It was because of [Malcolm’s] unwillingness to work as a team, his unwillingness to think beyond the transaction at hand…Most left the firm when I did…[one’s] “parting shot was: “I know, Malcolm, you think that you are the smartest in the room here at Whitlam Turnbull; let me include you in a secret: you are alone in that belief.””

DITCHING THE QUEEN

That belief flowered of course, and Turnbull, disgusted with the thought that Australia could share a head of state with another country, formed in 1990 the Australian Republican Movement. He opines: “Nobody could seriously contemplate leaving the powers of a directly elected president in the undefined, and thus potentially uncertain, world of convention” which perfectly encapsulates the superior stability of a distant crowned head following convention to a partisan local one bound by a set of constrictive and myopic rules.

He quotes himself: “Australians should be able to pick up their Constitution and find in it an accurate description of how their democracy works” which must seem to most Australians a curious reason for all the ensuing fuss. The referendum was a disaster for the republicans: a damaging rift over the right model arose, and the voters clearly decided that if wasn’t broke, why fix it.

During this time he encountered leading constitutional monarchist Tony Abbott, and he quotes Abbott in referring to him as “the Gordon Gekko of Australian politics.” Turnbull deploys the Soviet tactic of painting Abbott as not only weird but mentally ill, especially when he challenged and supplanted Turnbull as Leader of the Opposition and later when Abbott was PM. Yet there is something in Abbott’s slur that seems less than crazy.

POLITICS

To paraphrase Gough Whitlam paraphrasing Tacitus, “…everyone would have agreed that he was qualified for the post of Leader if he had not held it.”

Turnbull is reasonably intelligent, diligent, and good on detail. The chapters covering his time in the 4th and 5th Howard Governments, in opposition, and as a Minister under Abbott, are patchy but interesting. A policy wonk, his overweening vanity and overconfidence undermined his efforts, demonstrating again why businessmen often flounder in the murky soup of democratic politics (Rudd referred to Parliament House as “Chateau Despair.”)

His chapters on the River Basin Plan, the GFC and the NBN are good, albeit examples of him tackling problems too big for anyone, but his early conversion to Global Warming Theory reminds us that his education favoured humanities and his core competence was finance, not physics or geology: “And I understood then, as the decade that followed confirmed, that the fires, floods and droughts were getting worse and more frequent. And we knew why. It was precisely what the scientists had foretold would be the consequences of global warming...facing the dry and fiery consequences of a warmer climate, we have a moral duty to act...” The consequences for Malcolm’s moral vanity were to be more blatant.

He seems to have been, on more than one occasion, a reluctant usurper: after he defeated Brendon Nelson in a party-room ballot for Leader of the Opposition, he made some incredible blunders. One rather curious and irrelevant one was to be fooled into using a faked email against PM Rudd (‘Utegate’), which blew-up in Turnbull’s face when the fabrication was revealed (he had no part in that, his crime being one merely of naivity). The fundamental, critical misstep arose from his failure to read the signs that his colleagues were fed-up with Rudd’s messianic schemes and the Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme was the last straw.

Turnbull thought he had a moral and political obligation to support it: Joe Hockey challenged him but ran on a platform of deferring hard decisions on the CPRS, which revealed him as a political eunuch. Abbott, conceding he’d been something of a ‘weather vane’ on the issue, told Turnbull, apologetically, that he was sorry but he was going to have a go too, based on total opposition to such an idiotic scheme. (That principled conduct is not mentioned in this book).

Abbott won by a vote and eventually became Prime Minister. Turnbull endured many dark nights of the soul but was appointed by Abbott as Communications Minister, where he seems to have made the best of the mess that was the NBN, and renewed his love affair with the ABC. Possibly the most contentious parts of the book cover his shots at Abbott, including his alleged capture by Chief of Staff Peta Credlin, his charges that Abbott was a psychopath and his strangely supine response to a man he says was very dangerous, destroying the Party, and imperiling the nation. But in September 2015, he brought on a challenge – “not because I crave the limelight etc but because I know I would be a better, more contemporary, more liberal PM than he is.”

Part of the problem with these contentious portions is that Turnbull is his own source on important matters. On the Credlin issue, for example, he states that Michael Thawley, whom Abbott hired to head the Department of Prime Minister & Cabinet, was a “counterbalance to Credlin, whose influence and control he believed was excessive.” The source? Turnbull’s private diary, 14/11/2014, and we’re not told whether Thawley said as much, to whom, or if this is simply the diarist’s inference. (Actually, many of the diary entries sprinkled through the book, and the footnotes, struck us as passing strange.)

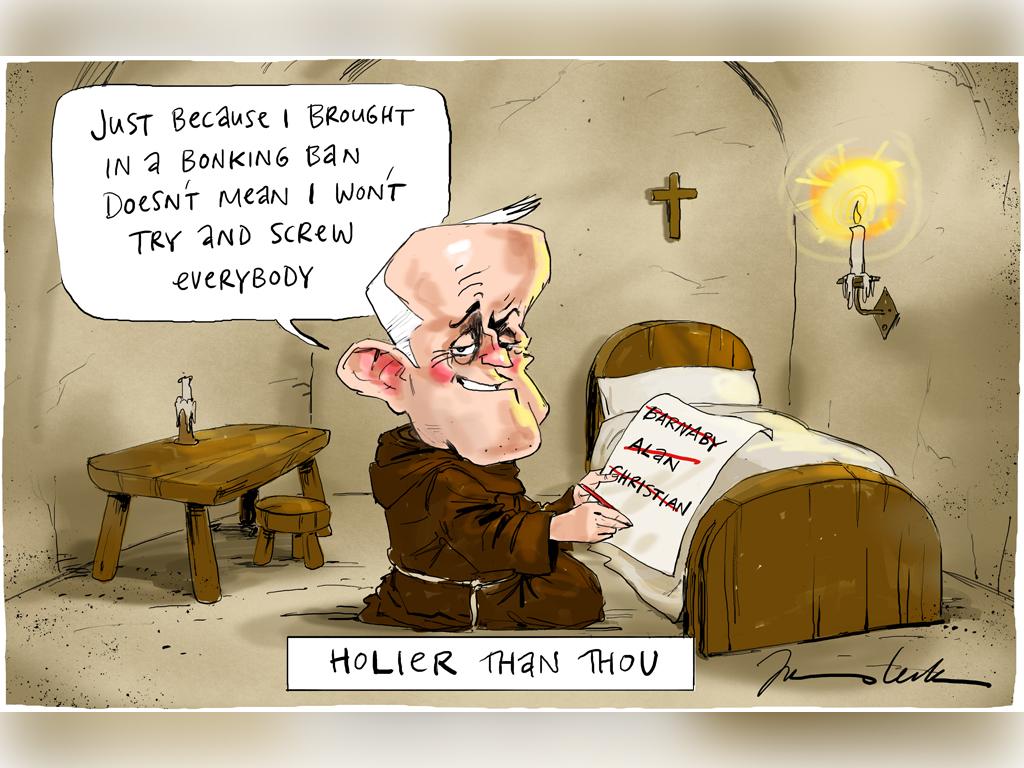

PRIME MINISTER

In any event, Turnbull, for all the ‘right’ reasons, masterminded an “elegant” coup against a man he calls a “besieged would-be tyrant,” perhaps forgetting that if this paints Abbott as Caligula, Turnbull is Claudius, a naive and flawed wowser whose edicts included a bonking ban and who was poisoned by his faithful servant. Before the reader shares the coup gastralgia, however, and the feverish ex post facto reasoning by which the author explains it, she has to wade through twenty or so chapters on the Turnbull government, some 350 pages of PM Turnbull’s legacy.

It is a slog, frankly. Instead of summarising it at length, we can synthesize Mr. Turnbull’s achievements thus: He (1) kept most of Abbott’s policies (including on the same-sex plebiscite, border control, national security, and the Paris CO² agreement), except for trivial flourishes such as Knights and Dames; (2) Spent like a drunken sailor on Gonski 2.0, a Julia Gillard initiative; (3) Renewed the Trans-Pacific Partnership, although without the US; and (4) Introduced a bonking ban on government ministers.

That’s about it. To be fair, although he did nothing much on tax, he had a go, and he flirted with grand schemes, à la Kevin Rudd (e.g., Snowy 2.0). But apart from hurling a lot of cash about and blowing numerous thought bubbles, there’s not much to show for almost 3 years, certainly not for the transactional over-achiever he was meant to be, one who “always wanted to get things done…to effect change, to effect reform.” This perhaps explains the disappointment of the very many who had high hopes for Turnbull. (He does get points for telling Rudd to go jump when Rudd – seriously – wanted support for a tilt at UN Secretary-General).

He does himself no favours, in the final analysis, by styling the push against him in the winter of 2018 as some sort of right-wing coup designed to bring Labour Leader Bill Shorten to the Lodge! Not only does this theory look completely deranged, and based on alleged hearsay statements that read literally mean no such thing, it also bears-out the comment of Ross Fitzgerald, reviewing the book in the 2/5/2020 ‘Spectator,’ that “it’s Abbott, rather than Turnbull, to whom the Liberal party really owes an apology.” This closing chapter of Turnbull’s is a sad coda to a fractious administration and a wasted political career.

One startling aspect of the author’s account of the coup is the failure to recognize he was dying by the sword he himself had wielded. He denounces what he refers to as the treachery, deviousness, and undermining by a “gang of right-wing thugs“, including a “foreign-owned media company'” in a mad design to blow-up Project Turnbull. He writes, apparently without irony: “Having been involved in many leadership challenges, it was all horribly familiar.” Indeed. The tactics deployed against him in August 2018 look a lot like those of September 2008 (Turnbull assassinates Nelson) and September 2015 (Turnbull assassinates Abbott).

Turnbull was Selectors’ choice for the White-anting Olympics, having eroded Brendan Nelson as party leader and Abbott as PM. Paddy Manning wrote in Born To Rule: “Turnbull pledged his loyalty to Nelson but gave him absolutely none. He simply refused to accept the decision of the party room, and the undermining began immediately.” So when Turnbull, on 21 August 2018 called a spill to demonstrate how much more loved he was than the despised Peter Dutton, who challenged, he was unpleasantly surprised to find that the vote was 48-35 in his favour, a margin so modest as to be untenable.

This increased the groundswell. Aware hostile forces in his own ranks were closing in, he released information that cast doubt on Dutton’s eligibility as an MP under s. 44 of the Constitution, and insisted that any challenge would need a public petition of at least 43 signatures of Liberal MPs. He thought that Dutton and his allies would struggle to amass that number, and he was right. But by Friday morning, he was given a petition with 43 signatures of his colleagues. His overthrow must have been awfully painful, for him and his family and friends, and he is eloquent about it. But one wonders if he felt even a stab of contrition, a soupçon of empathy, when he read that last entry on the petition? Signed by progressive Liberal Warren Entsch, the signatory added the words: “For Dr. Brendan Nelson.”

Reading A Bigger Picture, which is often interesting and informative, one is nevertheless reminded of Alexander Hamilton to Aaron Burr, who had asked “What was Washington’s most notable trait?” to which he replied: “Oh, Burr, self-love! Self-love! What else makes a god?“**

[NOTES * The Meaning of Conservatism, (2002), p. 13. And would a true conservative hang out with Vietnam protesters, Bob Carr, Jack Lang and Bill McKell, Bob Ellis, Laurie Brereton, Ray Martin, Neil Kinnock, Paul Keating, write for the Nation Review and originate the idea of the Guardian Australia? Turnbull states: “But as I reflected on the two parties, while I admired the romance and history of the Labor movement, I always felt I was a natural liberal, drawn to the entrepeneurial and enterprising.”Later he writes of admiration for Rupert Murdoch in the 1970s because he was, among other things, “politically progressive.” He does confront the smear that Turnbull approached Labor looking for a parliamentary slot and convincingly refutes it, but the fact remains that he would have been perfectly at home in the centrist wing of that party. He criticises Abbott’s government because it “lacked a coherent economic narrative” which would not be a priority, putting it mildly, for a conservative. And he quotes Jack Lang: “The Liberals have no loyalty or generosity – and no gratitude. The Labor party is at least sentimental.” (As if the latter quality was a good thing).]

————————————-

[**Burr, Gore Vidal, (1973).] [A note to the editor: This book has some repetition, some curious and unnecessary digression, and should have been cut (or, as politicians hate that word, ‘tightened’) by at least 100 pages. And we’re not sure these telling statements needed publication:“Inexplicably, we [Turnbull and Robert Maxwell] got on like a house on fire“;

“Turnbull & Partners …were more like Winston Wolf in Pulp Fiction – the people you call when you have a really bad problem“;

“I’m not a hater, as so many people in politics are“;

“Happily, Russel Pillemer and I had more to collaborate on than witness statements for the HIH Royal Commission“;

“I’ve always been pretty objective about myself, tending more towards self-criticism” and

“Peta [Credlin] has always strongly denied that she and Tony were lovers. But if they were, that would have been the most unremarkable aspect of their friendship.”]

Confucius say: Before you start on a journey of revenge, dig two graves.

[UPDATE NOTE: In the Sky Documentary by Chris Kenny, “Men in the Mirror: Rudd and Turnbull” (2 May, 2021), various insiders relate how alike these two antagonists are. Both were regarded as very bright, having great potential, yet failing in the top job. Driven, energetic egomaniacs, with lofty senses of their own superiority, they craved love and applause (both lost parents at an early, vulnerable age) and enthusiastically schmoozed the press to their advantage (and now demonize the same press having been forsaken). Which reminds one of the saying from the Old Testament, “Whoever shall be immersed in water for three minutes shall verily cease to be a c—.”] Continue Reading →Sundog

(Jeff Janoda. 2019)

We at TVC are not particularly interested in the experiences of German pilots stationed in Southern Russia in December 1942, and so we would not have picked up Sundog, had we not known that its author, Canadian Jeff Janoda was also the author of the terrific, Saga A Novel of Medieval Iceland. Janoda justified our faith. It would have been our loss, had we judged this book by its subject matter. The settings of the two novels could not be more different, but the concise, detailed and historically rich style are the same.

Better Call Saul (Series 4 and 5)

(#4: 2018 – #5: 2020)

The show goes on and Jimmy McGill, aka Saul Goodman (Bob Odenkirk) wends his way down the stairway of good intentions, towards Hell. We have already expressed our admiration for the parent production, Breaking Bad; and of the superb initial seasons of this inspired prequel, One, Two and Three: these next 2 series are just as good and increase the intensity of feeling for Jimmy and long-suffering partner Kim Wexler (Rhea Seehorn) as they hurtle towards a moral and existential abyss.

In series 4, Jimmy is reacting to his brother’s death by embracing an even darker, Byronesque morality; temporarily disbarred for the shenanigans with his brother over the Mesa Verde case, he is now eking out a living selling disposable cellular phones, and helping Kim cut legal corners. Eventually, he regains his licence to practice, but from now on, it’ll be as Saul. Meanwhile the perpetual war between cartel licensed rivals the Salamancas and Gus Fring waxes and wanes, embroiling Mike Ehrmantraut and Nacho Varga. Much of the criminal activity this season turns on the clandestine building of Gus’ underground, you-beaut, state-of-the-art meth lab, which leads to fatal results for members of the German construction team.

In series 5 (just completed: you can now binge-watch the entire 10 episodes) we really get to know (and fear, and loathe) a character introduced in season 4: Eduardo (‘Lalo’) Salamanca (Tony Dalton), one of Hector’s innumerable nephews, arriving from south of the border to help out after Hector’s stroke. Lalo is genial and hedonistic, but don’t let that fool you: he’s as friendly as a rattlesnake. (Indeed, he is pivotal in making Jimmy “a friend of the cartel,” a friendship no one needs or should want.) Dalton gives his character a multi-dimensional treatment that results here in something TVC did not anticipate: a man actually worse than all who have gone before. The game of chess he plays with Fring throughout is a high-stakes contest at which to marvel.

This story continues to be a wonderful, Dickensian saga, rich and full of apprehensive interest. Jimmy and Kim are the glue, of course, continuing to tease and tantalise us as to how they will end up: they are also gloriously (and plausibly) inconsistent and self-contradictory in their actions and morals. All of the key and supporting players are first class, as are the scripts, plots, setting and action. Don’t miss it and ‘hang onto your socks and hose’ for the next iteration!

Continue Reading →Theft by Finding

By David Sedaris (2017)

Having caught his act just before plague was upon us, TVC thought it a lucky ‘Rabbit Rabbit’ move to read his paean to serendipity, Theft by Finding. These are diaries kept by him (much winnowed; the originals comprise 8 million odd words, or 8 Clarissas) from 1977-2002 and as he so rightly argues in his introduction, diaries – proper diaries, the best diaries (Samuel Pepys, Anne Frank) – are written to find oneself, never with an eye to publication.

From his wastrel twenties to his successful mid-forties, his circumstances change but he hardly does, either in style or outlook, suggesting heavy edits of the early stuff. But the diaries (approached by us initially with dread, as with all diaries) are fascinating and compelling, deadpan funny in the most rough-and-tumble way. A good review of the book in The Guardian was preceded by the following sub-title or watermark: “The humorist’s material includes drug addiction, crazy jobs, his eccentric family and homophobic abuse – but much is achingly funny” which seems to us a deliberately virtuous fudging, in that the drugs, squalor, insane relatives and aggressive sexual weirdness are all achingly funny.

We recommend a reading of this from go to whoa, and you see a life unfolding in a sort of real time, camouflaged but not blotted-out by a myriad distractions and situational cul-de-sacs. Or you can read it in a random fashion, like digging for truffles; it is a rich field. Some examples we hope suffice to demonstrate the point:

“I’m in a seafood place drinking coffee. I need to get to Raleigh, but so far rides are sparse. I have a joint and $3. I remember being appalled when David Larson hitchhiked to North Carolina with $1 in his pocket, and now here I am. I started the day with a ceramic pig but abandoned it after it got to be a drag to carry.” (Dec. 1, 1977 West Virginia)

“While listening to a country music station, we heard a talk/song narrated by our flag. “I flew proudly at Iwo Jima and on the blistering deserts of Kuwait, anywhere freedom is threatened, you will find me.” The flag recounted being torn into strips to bandage wounded soldiers and then it explained how it hurts to be burned and trampled by the very people it works so hard to protect. When given a voice, our flag is not someone you’d choose to spend a lot of time with.” (Oct. 28, 2002 New York)

“The woman at the phone company addressed me as “Mrs Sedaris” until I couldn’t stand it anymore and corrected her. That always happens. They think I’m a woman – a woman named David.” (Jan. 13, 1982 Raleigh)

“Harry Rowohlt, the fellow who translated my book into German and is reading with me on my tour, told me that when someone on the bus or at a nearby table in a restaurant talks on a cell phone, he likes to lean over and shout “Come back to bed, I’m freezing.”” (May 18, 1999 Cologne)

“Last night I went crazy for marijuana. I was Jack Lemmon tearing up the greenhouse in Days of Wine and Roses. I looked for (and found) pot in the folds of album covers I had used to deseed long-ago ounces and quarters. I found some under the sofa cushions. Then I pulled out the couch and looked under the radiator. I turned the place inside out and got a little stoned but not much.” (Feb. 15, 1982 Raleigh)

“Last night, after finishing the cabinets, I went to the little market around the corner for beer and found $45 on the floor in front of the checkout counter. I thought I’d dropped it, and by the time I discovered it wasn’t mine, I was back home. First thing today I went out and blew it. I bought: 1. two pounds of goat meat 2. more beer 3. Fires by Raymond Carver 4. the New York Review of Books 5. hardware 6. groceries 7. a magazine called Straight to Hell in which gay men recount true sexual experiences, many of them outdoors and in cars or under bridges” (Jan. 22, 1984 Chicago)

“I’d never noticed that Ronnie had a mustache, but still it upset her. When she got home she told Blair, who said she’d probably feel better after a shower and a shave.” (July 4, 1988 Chicago)

“I will never again drink at a party I am hosting. I will never again drink at a party I am hosting. I will never again drink at a party I am hosting.” (Jan, 15, 1989 Raleigh)

“Walking down 8th Avenue, I fell in behind two muscled gym queens. When a a car alarm went off, one of them turned to the other, saying, “That’s the Puerto Rico national anthem.” “Really?” the other guy said. “That’s actually their anthem?”” (Sept. 4, 1992 New York)

“Meanwhile, channel 13’s Nature special was devoted to cats. Hugh and I switched back and forth from musical to musical to the mother calico teaching her young to hunt. It’s a lesson that Dennis, our cat, apparently slept through.” (Feb. 10, 1998 New York)

“The teacher threw a lot of chalk today, but none of it at me. We have a new student, a German au pair, and I wonder what she must think, watching people get yelled at and hit with things. Our last homework assignment was handed back, and though I’d technically made no mistakes, she still found fault with it. I’d written, for example, “You will complain all the time, day and night.” Her comment read, in angry red pen, “Pick one or the other. You don’t need both.”” (Sept. 14, 1998 Paris)

“On the way to the bookstore I asked Frank, the escort, what he thought of my bow tie. He hesitated for a moment and then said, “A bow tie tells the world that the person wearing it can no longer get an erection.”” (June 13, 2001 San Francisco)

“I think in Hungary they give a star for electricity, a star for heat, a star for running water, and so on. The fourth star signifies that the Astoria has cable TV. They boast forty channels, not mentioning that twenty-three of them broadcast the exact same programs. Our hotel is fronted in scaffolding, and our rooms offer a view of a mangy, narrow side street. The one thing they excel at here is stoking the furnace. It’s below zero outdoors, while inside our rooms we could roast chickens by leaving them on the nightstand. There’s a large group of French people at the hotel and I heard one woman saying she’s so heat-swollen that her rings no longer fit.” (Dec. 17, 2001 Budapest)

“Little, Brown forwarded an envelope of mail, and I realized after reading it over that every single letter wanted something from me. The senders included: a college student writing an article on magazine readership. “I’m on deadline so email me as soon as you get this!”…an Indianapolis human rights group wanting me to attend their rally. “Your agent says you haven’t got the time, but I suspect you do.”“(March 9, 2002 La Bagotière)

“Dad has rented an apartment to Enrique, one of Paul’s employees, and Enrique’s mother…She’s in her early sixties and was recently hospitalized for depression…it’s hard to adjust when you have no friends and can’t speak the language. Dad decided that her problem was low self-esteem. Work would make her feel needed, so he hired her to scrape paint. It was only a two-hour job, a $16 opportunity, but after ten minutes he snatched the tool from her hands. “This is how you do it!” he yelled. “Like this.” When she failed to catch on, he screamed at her all the louder. “Oh, get off it. You know what I’m saying.” The episode left her more depressed than ever, which, Paul says, is the way it works with the Lou Sedaris Self-Esteem Program. “You’re a big fat zero is what you are, so here, scrape some paint.” A foreigner will learn the phrases “Can’t you do anything right?,” “Everything you touch turns to crap,” and “Are you kidding? I’m not paying you for that.”” (June 13, 2002 London)

[And by the way, with the profoundest respect, the diarist is wrong: The Wire was overrated.] Continue Reading →